- Home

- #ToYouFromTes: A word to the wise

#ToYouFromTes: A word to the wise

Knowledge and wisdom: philosophers tend to mistrust abstract nouns like these. Instead of asking “What is knowledge?” or “What is wisdom?” we like to look at more everyday uses. Some people know what’s what, or who’s who, and many know that the Earth is roughly spherical and that the atmosphere is currently warming. Other people seem able to invest wisely, or eat or drink wisely. In these ordinary cases there is not a huge contrast: if we think a couple has brought up their children wisely, we might equally say that they knew how to bring up their children well.

But some know-how seems to have little to do with wisdom. You cannot naturally be said to play golf wisely, however low your handicap and however well you know how to drive and putt. You might, however, wisely devote a certain amount of time - possibly none - to golf itself.

Knowledge has had the most attention in education and in the Western philosophical tradition. Plato suggested that knowledge was true belief plus a logos, meaning something akin to a reason or rationale. The idea was that a lucky guess or hunch might turn out to be true but it would not have the right backing to count as a case of someone knowing something. Logos would be whatever takes luck out of the picture. Careful observations, reasonable inferences, trustworthy sources, track records of success and general reliability all contribute to this, and sometimes clinch it.

Done and dusted

When we then allow that people know something, we accord them a status. They can call the question closed. It is done and dusted, the answer is in and further inquiry is unnecessary. Or so we allow - but we may be wrong.

Questions sometimes need reopening later, however firm the ground may have seemed at the time. But when we suppose a question is done and dusted, we trust the answer and, across countless interactions with other people and with the natural world, we need that trust. We do not want ourselves, nor our doctors, engineers, navigators, food suppliers nor our justice systems to be guided only by guesswork. We need to hope that they know what they’re doing, and that we do as well.

Former education secretary Michael Gove must have forgotten this when he said that the people of Britain have had enough of experts. He was presumably generalising irresponsibly from his own career, forgetting that even a politician needs society’s expertise. They need to clothe themselves, wash, eat, drink, travel, consult doctors and lay plans, relying all the time on countless things that they and other people know. Politicians can only guess and posture and consume lies and sound off in the expertise-free, post-truth world of their own profession.

There is no point, then, in knocking knowledge, although there is certainly a question about which things are worth knowing. A prime signal that something is worth knowing is that it is at the service of an important know-how or ability. For example, it is valuable for me to know quite a lot about the geography of Cambridge, since I frequently need to find my way around the city. I do not need to find my way around Vladivostok, however, and have almost no expectation of ever needing to do so. Hence, I do not regret my ignorance of its topography.

To translate this to education, if I were forced to sit in a classroom being instructed in the geography of Vladivostok, I would be as bored and restless as any child in its least favourite class. This is why, to be a good teacher, you have to first catch, or create, a learner’s interest.

What then of being wise? What is the contrast with being knowledgeable, and is wisdom teachable? Socrates, it was said, was the wisest of men because he knew how little he knew. To be wise, this suggests, you need to be modest. Insofar as people claim the status of knowing things when they do not, they are failing in wisdom.

But there is more to it than that - the people who bring up their children wisely are not only modest but they have a kind of “touch”: across a wide range of situations, they seem to know how to judge and how to feel about things. They have a kind of practical ability or what Aristotle called phronesis. They judge rightly what is required.

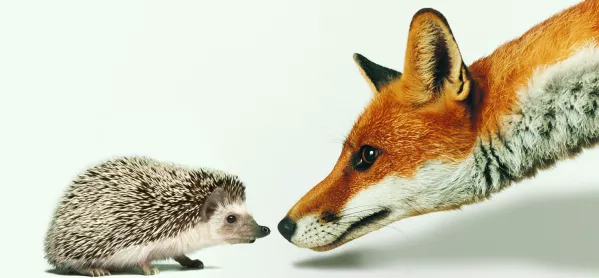

The fox and the hedgehog

The fox, says the proverb, knows lots of little things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Perhaps the one big thing that the wise person knows is how to feel about things or how to judge them. Feelings incubate choices and actions, and for those who are wise, these turn out, consistently, to have been the choices and actions that the situation indeed required.

Although this is surely on the right lines, we need to note that the contrast with knowledge is far from sharp. A wise general may indeed judge rightly that the situation requires, let us say, a feint on the left and a sally on the right. But he cannot judge or “feel in his bones” that the situation requires this without knowing a great deal about the situation. He needs to know how the enemy is arranged, and that his troops have or have not the will to win and the means of doing so. Indeed, there is no limit to the amount of knowledge he may need to deploy in order to judge rightly that the moment is at hand for a feint on the left and a sally on the right. Wisdom in the conduct of the battle does not come at the expense of knowledge but rides on its back. The hedgehog needs the assistance of the fox. But the wise general also picks up which information he needs and discards what he does not need: so the fox also needs guidance from the hedgehog.

So what are the pedagogical implications of all this? If wisdom were entirely a matter of sage withdrawal from the world, teachers could not teach it but neither should they particularly want to do so. Hermits must find their own way to salvation. But in the complex business of living, acquiring a “touch” requires practice and exposure, growth and experience. Knowing what to feel about things, or knowing what the situation requires, indeed goes beyond just having true propositions at your disposal. It is best practised in conversation and dialogue, or what TS Eliot called “the common pursuit of true judgement”.

The Socratic discipline of philosophical discussion teaches people the civilised lesson that their first thoughts are not always their best, and that reflection often brings improvement. It teaches them that shouting loud is no substitute for thinking hard. It teaches them to think and to listen.

But since the hedgehog also depends on the fox, we cannot aim at wisdom at the expense of knowledge. What we can do, however, is to cultivate judgement alongside the cultivation of knowledge.

Simple chronology

Consider, for instance, the teaching of history. At the lowest level, there is what the philosopher of history RG Collingwood called “scissors and paste” history: the simple chronology of events. Even here, there is selection and judgement. There are decisions to be made about which events to include and which to leave out; which to emphasise and which to downplay, whether to talk much of personalities or much of social movements, and so on, endlessly. Here, catching or creating the learner’s interest is vital. But for Collingwood it is only once the scissorsand-paste part is over that history proper begins. The interpretation or understanding of the events in the record requires an imaginative process: the “re-enactment” of the thoughts and feelings of the historical agents who brought about the events in the first place.

It is here that the first step beyond mere knowledge and towards understanding and thence towards practical wisdom occurs. The imaginative re-enactment develops a sensitivity, an understanding of the human world, and this is an indispensable component of wisdom.

Without this understanding, the words of a chronicle lie dead on the page, and it is impossible to think why anyone would be interested in them. The danger then is to drum up an interest by ideological invention, which is how we end up with Our Island Story, The White Man’s Burden, and the like. When the words lie dead on the page, they will be of no help to you feeling and judging rightly about things, but if you have been actively misled or brainwashed, what passes as history may actually prevent you from doing so.

Probably until very recently, most English and Americans unwisely lived in a little bubble of complacency about our historical superiorities. We were not as other nations, subject to the madness of crowds. We were not going to turn our backs on our constitutions, or install dictatorships or rage against the rule of law. So we were unprepared when Brexit and Trump reminded us of our kinship with other, less enlightened, parts of the world and periods of history.

John Stuart Mill said that “no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs”. It is doubtful whether this doctrine is consistent with the other elements of his utilitarianism but there should be little doubt about its general truth.

Temporary effects

Perhaps it needs qualifying slightly, since instruction often has only temporary effects. I was once an instructed person, meaning that for one short week in the summer of 1961, I could repeat enough facts to gain 98 per cent in what was then known as the S-level chemistry examination. A month later, my score would have been about half that and now I have forgotten virtually all of it. True, I did not “consent” to this diminution but then neither do I much regret it. After all, I was not going to become a chemist. I have had no cause to use any of those wonderful facts.

So knowledge passes. But even so, it can leave a smattering of wisdom. The exercise gave me a proper admiration, I hope, for the stalwarts who have gone on to use their scientific knowledge to do great things. It opened my mind to disciplines and skills. It has helped to prevent me from feeling sympathy with Gove’s protégés who have had enough of experts. In other words, it has helped me to feel and judge rightly of the relative merits of learning and ignorance - and that is a little bit of wisdom that I would be absolutely mortified to be without.

Simon Blackburn is a fellow of Trinity College, University of Cambridge, research professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and professor at the New College of the Humanities

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters