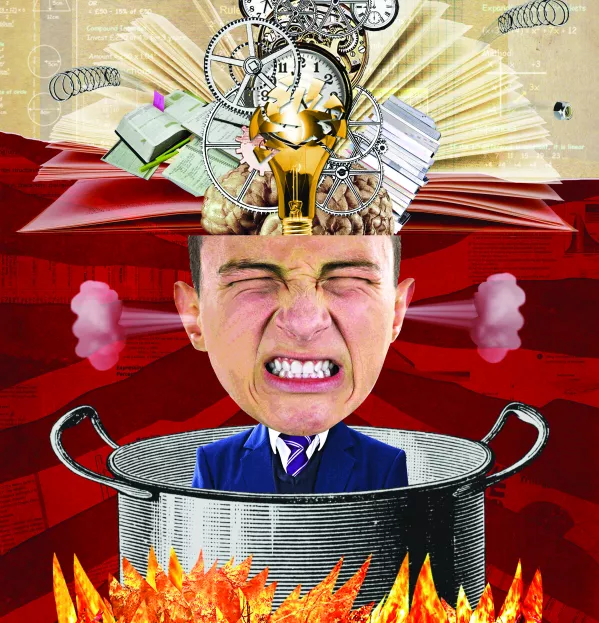

Are GCSE reforms really behind increased exam stress?

Three years ago, I might have had one child who was suffering with severe exam anxiety, where they’re losing sleep, they’re considering dark thoughts,” says Sarah Bone, headteacher of Headlands School in Bridlington.

“I can honestly tell you now that there are probably between 10 and 15 of my children in Year 11 who are having serious, significant dark thoughts around this summer’s examinations.”

Today, on the cusp of the summer exam period, student stress will be at the forefront of many teachers’ minds.

Although most pupils hopefully won’t be in the category that Bone describes, a lot of teachers will share her concern that exam stress has increased in recent years, with many pointing the finger at the government’s qualification reforms.

However, the assessment regulator Ofqual has denied this suggestion.

Appearing in front of the Commons Education Select Committee last month, Ofqual chair Roger Taylor said that his organisation took “extremely seriously the evidence of growing levels of anxiety” among young people. But, he said, “the evidence does not support the view that it is the way that exams are designed which is the issue”.

What do teachers and students think about that statement? How did Ofqual reach that conclusion? And, most importantly, what can schools do to relieve the exam stress that is out there?

It’s not difficult to find teachers and school leaders who disagree with Ofqual, and Bone is one of them. “I would strongly refute [Taylor’s assertion],” she says. She believes reforms to GCSEs and A levels that scrapped modules and coursework have put pupils under greater pressure. “They’ve got nothing in the bank, so to speak. They’ve got nothing to fall back on.”

As a result, everything hinges on a beefed-up exam period. “There is this overwhelming sense of responsibility to perform for a sustained period of time, four weeks, over 30 hours of exams,” Bone continues. “I just think it’s enormous.”

Stephen Rollett, curriculum and inspection specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), says most headteachers would share that view. “Our members are telling us something very different to the picture that Ofqual have painted, and what [the members] are telling us is that exam stress has worsened as a result of the reforms to GCSE.”

Rollett says it’s not just the move to linear examination. When Michael Gove was education secretary, he explicitly reformed GCSEs with the intention of making them more “demanding”, and many teachers say they have struggled to cover the expanded course content. “We’ve heard back from school leaders that what’s at the root of the issue is more content,” Rollett says. “Perceived greater difficulty” and “fewer practice papers” have also contributed to stress, he adds.

At this time of year, students will certainly tell you that they’re feeling the pressure. Nina Taylor, who is currently preparing for her GCSEs at Varndean School in Brighton, tells Tes: “I feel like everyone’s getting more stressed as they come closer…If I haven’t revised in a day, I feel like I’m not calm going to sleep.”

Rachel (who asked for her surname to be withheld) is revising for her A levels at Farnborough Sixth Form in Hampshire. She feels that “one fluff” in her exams could “completely change the entire course of my life”. While she knows it’s not going to decide whether she’s a success or not, she points out that, based on her firm and insurance university offers, it will determine whether she goes to an institution “right up north or right down south”.

Both students believe that the assessment structure they are working through is more stressful than the system that some of their recent predecessors faced. “I personally much prefer coursework, because you’re given a lot more time to do it and you can take it home and do it in your free time,” says Nina. “I definitely think less coursework brings more stress,” Rachel agrees.

Rite of passage?

One gets the sense that Nina and Rachel are smart, conscientious students, and they appear to be on top of their nerves. Of course, anxiety about exams is as old as exams themselves, and many teachers believe that - in moderation - it’s healthy.

Duncan Byrne, the head of private Loughborough Grammar School, believes that pressure on young people has “definitely increased”, which he thinks is partly linked to the Gove reforms, but also higher grade expectations among “the top level of universities”. But he consciously prefers to use the word “pressure” rather than “stress” in relation to exams. “It’s part of life,” he says. “People in most jobs are under pressure every week…I think we’ve got to frame it as one of those rites of passage that needs to be gone through”. That being said, running a private school brings its own challenges - such as having to rein in excessive parental expectations during the revision period.

While Byrne is relatively sanguine on the subject, he acknowledges there is a group of students for whom exam anxiety is a much more serious issue. He says that he has about two students a year who find the pressure “really difficult to deal with”, and who might require medical support and special exam arrangements.

Bone has an increasing number of pupils who are grappling with a worrying level of exam anxiety. When asked how this stress manifests itself, she reels off a disturbing list of symptoms. “Increasing amounts of self-harm. That’s not necessarily just through physical cutting - that could be through eating and not eating. Anxiety - we’ve had an increased number of panic attacks in the last three years among young people, getting incredibly anxious and feeling very overwhelmed…Suicidal thoughts [are] becoming more prevalent.”

Another teacher, who teaches history at a comprehensive in the South West but who preferred not to be named, painted a similarly concerning picture.

“I’ve had kids crying in class and unable to cope with their workload,” she says. “They do extra work and request extra revision sessions even though they’re already doing more than they need to. Even key stage 3 students are focused on grades over progress or learning experience. Feedback from kids on their wellbeing is frightening. Many feel overwhelmed and mental health difficulties are an increasing problem.”

In the light of such distressing accounts, and with most teachers feeling that exam reforms have played at least some part in rising stress, why hasn’t Ofqual reached the same conclusion?

When Tes spoke to Ofqual about the issue, the exams watchdog acknowledged that the research does indeed suggest that levels of anxiety and depression among young people appear to be on the rise. But it said this is a decades-long trend, which is also complicated by growing awareness and openness about mental health - something that all the teachers to whom Tes spoke acknowledged. On the key question about whether exam reforms are to blame, Ofqual said the longitudinal data simply does not exist to say this definitively.

Ofqual also maintains that the evidence is patchy on what form of assessment is most stressful. While there does seem to be evidence that students prefer modules to linear exams, Ofqual said that under some modular systems students report higher workload. And while students seem to prefer coursework, they also say that competing coursework deadlines can be stressful for them.

What about the charge that a monster exam period has increased stress? When Ofqual appeared in front of the education select committee, Taylor said that “the actual amount of time spent under exam conditions has not increased because controlled assessment has been taken out of many qualifications”.

Many teachers will feel that he’s missed the point. Sitting in a silent exam hall and turning over the paper on the desk in front of you is just a “different thing” to controlled assessment, Rollett argues.

“It’s that moment of high stress, knowing that in that moment what you do really matters,” he says. “A prolonged piece of coursework over a period of time doesn’t deliver that peak of high stress.”

There are other elements of Ofqual’s review of the literature on exam stress that might start alarm bells ringing for teachers. Ofqual found that “academic perfectionism” - the idea that students have to get top grades - can exacerbate stress. The research also suggests that the more predictable and familiar a test is, the less anxiety it provokes.

It’s easy to see how reforms, increasing differentiation at the top end with a grade 9 at GCSE and an A* at A level, and rhetoric about “raising the bar” could encourage perfectionism. And while Ofqual protests that exam boards produced a large amount of specimen material prior to the new exams, teachers and students still feel they have been navigating uncharted waters.

To be fair, Ofqual is at pains to point out that its comments are limited to its interpretation of the existing research - it doesn’t deny the lived experience of students who say they feel anxious about exams.

Hothouse of cards

So how can schools support GCSE and A-level pupils and try to minimise stress? Byrne thinks it’s about preparation and normalising exams. “What we try to do over their time at the school is to get them used to taking tests,” he says. “We’re trying to make them realise that this is actually part of your education, so that GCSE doesn’t hit them like a freight train.”

Of course, if not managed effectively, this preparation can result in a hothouse culture that ramps up the stress even further. And one of the reasons some teachers believe exam anxiety has become so acute is because it’s not just the students who are being measured. Schools, heads and teachers are all under the microscope because of the accountability system.

“It is difficult,” admits Bone. “Ultimately, I’ll be measured as a teacher based on this cohort of kids’ results next year. I’m due an Ofsted inspection again, and I will be measured, as will my team, on how these students perform.”

Whether or not exam stress has got quantifiably worse because of the reforms, it’s a huge issue for schools. The good news is that there are plenty of things that teachers can do to help.

Lisa Fathers, head of the teaching school at Bright Futures Educational Trust in Greater Manchester, who is piloting a mental health project across 120 schools, says it starts with culture. It’s about having “a really open culture, and a culture that means that kids and staff can say, ‘Hey, I’m not OK, I’m not coping’. Make it OK to not be OK”.

This article originally appeared in the 19 April 2019 issue under the headline “‘Can they stand the heat?’”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters