Exit strategy for the overheated

There are two ways to treat badly behaved pupils: like criminals who deserve punishment, or like people whose emotions occasionally get in the way of their ability to interact appropriately with others.

Mike Temple, a behaviour consultant and former special needs teacher, says schools too often adopt the first method, but that punishment perpetuates misbehaviour.

He has developed a method he calls “supportive behaviour management”, which he recently trialled in primary and secondary schools in the South East.

“Often, schools have a low tolerance of low-level disruption,” he says. “Punishment is applied without looking at context: whether a pupil’s mother is ill, or they’re looking after their sister perhaps. How can you teach emotional intelligence but run a punitive school?”

Mr Temple recommends that, instead of doling out detentions, teachers should acknowledge that, just as they have bad days, so too do pupils. So, when a teacher and pupil find themselves in a stand-off, the first thing to do is separate them.

He suggests establishing one or two time-out rooms, each staffed by at least two teaching assistants. Pupils would go to the room after any instances of misbehaviour, and one of the teaching assistants would ask what had just happened.

“They would say, `I understand how you feel. I understand why you reacted the way you did. But how might you react next time?’” Mr Temple says.

“Gradually, pupils learn that maybe their reaction was a bit hot and not right for that moment.”

The time-out room staff would also offer coaching for the teacher, discussing with them how best to receive the pupil back into the classroom.

“If the child goes back and the teacher says, `Yes, and don’t you dare speak to me like that again,’ then the whole situation starts again,” Mr Temple says.

“The child will get things wrong, but how you deal with that is up to you. You can be angry, you can be disappointed, or you can be supportive.”

For some pupils, it could take half a day to reach a point where they are calm enough to return to the classroom.

But once the behaviour management policy has been in place for some time, pupils could progress from incandescent rage to quiet acquiescence within five minutes.

Eventually, teachers would learn to pre-empt misbehaviour: if a pupil seems to be struggling, for example, the teacher could suggest a visit to the time-out room. Similarly, pupils could choose to leave the classroom before they lose their temper.

“Some of them have huge emotional baggage,” Mr Temple says. “Children don’t do things to you; they do things for themselves. What they’re feeling comes out.

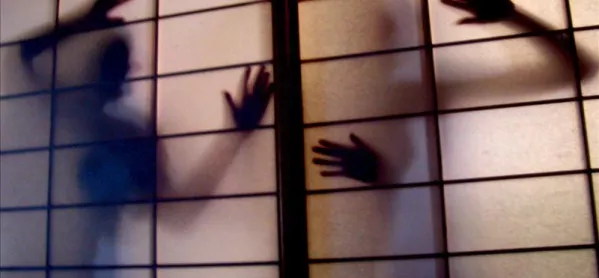

“But you see very angry children gradually calming down because there’s an escape route. There’s a route to quiet.”

www.thelifeskillscompany.com

A KENT CLIMBDOWN

Behaviour at Greenfields Primary was once so bad that pupils were literally climbing the walls.

“Children would shout at staff, walk out of rooms, and generally be very quick to fly off the handle,” says Janet Herbert, who was head of the Kent primary until July this year.

Determined to get their own way, many climbed walls and staircases, putting themselves at significant risk.

So Mike Temple was invited in to look at the school’s behaviour policy.

“He helped provide us with a fair system for pupils to explain their actions, to address the causes of anger and aggression,” says Ms Herbert. With his help, pupils learnt that the world would not change to fit their behaviour, that they would have to adapt their behaviour to the world.

At first, staff were put off by the paperwork and effort involved. But gradually they came to see the benefits of the new approach, learning to choose their words carefully, so that pupils did not feel they were being shouted at.

“Pupils began to believe that someone was listening to them,” says Ms Herbert. “Trust developed quite quickly, and the school felt like a different place. Some very aggressive young men, in Year 6 particularly, were able to communicate on a fairly mature level. There’s a very healthy, positive atmosphere now, a sort of respect for one another that comes through.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters