Forget them not

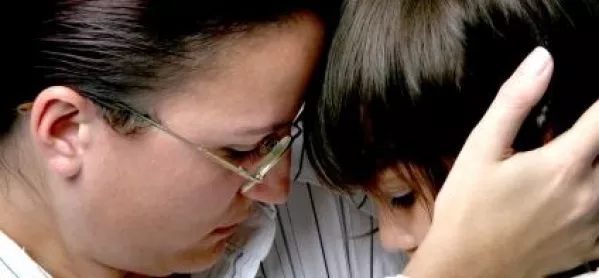

Tugela (Tiggy) Rose Frankel was seven years old when she and her grandfather were killed in a car accident. Her death this August was difficult and painful for her teachers and young classmates to digest.

But through the turmoil, Wylam First School in Northumberland was able to help staff, pupils and Tiggy’s family cope with their grief. It also offered a glimmer of happiness and hope in the shape of a moving memorial service, which it co-ordinated with Tiggy’s parents.

“After a terribly sad event like this, we needed to give support to the whole school community as well as the family,” says Lynn Johnston, head of Wylam School. “You can’t rush it. Difficult emotions or issues will keep re-surfacing over a considerable amount of time - and I’m talking years, not months.”

Death is an inevitable part of life, but its discussion in schools is anything but. Seventy per cent of schools are likely to be dealing with bereavement at any one time, according to research produced by Shelley Gilbert, a child counsellor. And despite a willingness to help, a fear about saying the wrong thing often prevents teachers from addressing the issue.

But, Shelley, founder of the Grief Encounter Project, a child bereavement charity, says: “These children will be upset anyway. You’d have to work really hard to upset them more. Pupils need to know they can talk or release some pressure if they need to.”

Wylam School does not shy away from the subject. The first thing visitors see when they enter is a small picture of Tiggy, propped up on a prettily displayed table. When a tough, football-loving boy starts to cry in class, the lesson is put on hold so that everyone can talk about the accident and how they feel. And the day after the memorial, when the pupils are tired and fractious, afternoon classes are replaced with a film.

“Our staff can read the pupils’ emotional health well,” says Lynn. “If they’re not ready to learn, we don’t force them.”

Looking after the needs of the teachers is equally important. An educational psychiatrist discussed the accident with staff before term started, allowing them to chat through coping strategies together.

The next day, Lynn gathered the whole school in the hall. “I lit a special candle and told the truth,” she says. “I was nervous, but determined to be very matter of fact.”

Pupils were told that it was OK to cry or feel angry. Now, if they need to talk or leave the classroom, their teacher allows them to talk to an adult or a friend in a quiet place.

Identifying a key member of staff who can give time to the most affected people is essential. In some schools, it will be the Senco or form tutor; in others, the most apt person is obvious.

At Wylam, that person is Becky Kroese. She came back early from holiday to attend the funeral, and became a frequent visitor at the Frankels’ home. “I do home visits before I meet my new class anyway, so the children can get to know me before school starts,” says Becky, who teaches Tiggy’s younger sister, Poppy, in reception. “I wanted Poppy to be able to trust me and talk through her feelings before term started.”

Becky regularly sends Poppy’s mother reassuring text messages about her welfare during the school day. She also suggested and facilitated ideas for the memorial service, including hanging star-shaped messages on the branches of a tree and a scrapbook of classmates’ memories.

Jill Adams, schools’ training co-ordinator at the Child Bereavement Charity, says that every teacher has the skills to support bereaved pupils in this way.

“What children most need is someone who cares about them and who’s prepared to listen,” she says. “Most teachers can offer a huge amount of help by carrying on doing what they always do.”

However, teachers need to be aware of potential pitfalls as well. Grief may seem to recede, only to re-surface at stressful times, such as the move from primary to secondary school.

“Sometimes primaries forget to mention to the new school that there was a death years earlier,” says Jill. “This can cause unintentional upset, such as when a teacher unknowingly plays music that was last heard at the funeral. New teachers must know what they are up against.”

The anger associated with grieving can also cause challenging behaviour, especially among teenage boys. Jill often comes across boys who are excluded from school, only for teachers to discover that there was some ignored bereavement in their past.

The secret is for teachers to remember the long-term implications of bereavement. “People usually learn to live with grief, but they don’t ever forget it,” she says.

Classroom-based activities can keep the topic alive, but it should be led by pupils’ wishes. “People can make good-willed assumptions about what the child needs,” says Jill. “The classic example is providing bereavement counselling when the majority of children don’t need or want it. They’ll appreciate being asked.”

www.griefencounter.org.uk

www.childbereavement. org.uk

How teachers can make a difference

- Write a bereavement policy, including a list of useful resources, contacts and support groups.

- Appoint a school bereavement worker to liaise with and support the family and school community.

- Use straightforward language. Avoid expressions such as: “They’ve gone to sleep”. It may confuse younger children.

- Always acknowledge that someone has died.

- Don’t rush the grieving process. Be prepared to support pupils over a number of years.

- An upset pupil will struggle to learn; try not to force them back to school before they are ready.

- Be prepared to deviate from a lesson plan to discuss difficult emotions that arise, or include death in the curriculum.

- Give pupils a time-out space if they need to be alone or discuss feelings. Time-out cards are a good non-verbal option.

- Don’t forget to support staff, especially the key bereavement worker.

Quick memorial ideas

- Create a memory book or box.

- Have a small candlelight ceremony.

- Put memories in helium balloons and release them.

- Create a piece of art or sculpture with a local artist.

- Plant flowers or a tree in dedication.

- Put up message boards for pupils to write on.

What to avoid

- Letters sent home addressed to both parents, long after one has died.

- Setting an essay subject on a sensitive topic such as “The five people you would most like to meet in heaven”.

- Reports that make reference to a pupil having time off or unauthorised absence, when they were grieving or visiting relatives.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters