- Home

- ‘I remember being an outsider’ - the teacher at the centre of LGBT row

‘I remember being an outsider’ - the teacher at the centre of LGBT row

It could almost be a script from a Hollywood movie. In the space of a week, Andrew Moffat went from enduring bitter protests outside his school gates calling for his sacking to being feted in front of royalty as one of the world's best teachers.

The assistant head of Parkfield Community School in Birmingham has been under the national and international spotlight for weeks. Abroad, he has been honoured as a finalist of the $1 million Global Teacher Prize. But at home, he is at the eye of a storm about what community cohesion and conflicting values mean in modern Britain.

There are serious issues at play in the controversy surrounding the No Outsiders lessons he devised and it can be easy to forget that there is an individual human being – a teacher in a local primary school – caught up in something that has become so much bigger than him.

Watch: Peter Tabichi wins $1m Global Teacher Prize

Quick read: Ofsted praises school at centre of LGBT row

Background: Teacher shortlisted for global prize

So, how has he coped?

'No Outsiders is community cohesion'

Moffat was made an MBE for services to equality and diversity in education in 2017 for his development of the No Outsiders programme. He designed the course in 2014 to cover a child’s seven years in primary school, and it has since been adopted by schools around the country.

The aim is to help pupils understand and accept the diversity of people in modern Britain.

As Moffat explains it, “No Outsiders is community cohesion. It’s about different people in the UK today, it’s about Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Sikh, black, white, brown-skinned, disabled, gay and lesbian, different families.”

It has become controversial in recent weeks because of the "different families" LGBT element, and some Muslim parents have held demonstrations outside his school calling for the lessons to be scrapped.

The school has now suspended the programme pending discussions with parents – a move Moffat supports – but he stresses that No Outsiders is not about “LGBT lessons”, and only four of the 35 lessons have an LGBT focus.

And No Outsiders does not, Moffat also stresses, have anything to do with sex education.

“If you ask any four-year-old in our school ‘What’s No Outsiders about’, I know they will all say the same thing: 'We all play together. No-one’s left out.'”

'I used to live on Smash Hits'

The origins of No Outsiders are deeply personal.

Although Moffat did not know he was gay when he was at primary school, he says he was “always different to the other boys”. The separate boys’ and girls’ playgrounds at his middle school was “horrific for me”.

“The whole No Outsiders thing does come from that. We are all products of our youth, and I remember being an outsider, especially in that boys’ playground.

“I have really hard memories of being on my own, literally by the wall, because I couldn’t relate to any boys. There were very few boys who were prepared to come and talk to the ‘poof’, which is what it became quite quickly.”

Many of his reference points came from pop culture – “I used to live on Smash Hits” – with figures like Boy George, Marc Almond and Frankie Goes to Hollywood prominent, although Bronski Beat and Jimmy Somerville were “the closest to what I thought maybe a gay person was”.

One memory, in particular, is seared into his mind.

In the 1980s, gay people were rarely seen on TV, so he was desperate to watch a Channel 4 documentary about lesbians.

“I can remember the first scene. It was a lesbian family sitting having a picnic in a park, and I can remember it clearly, mum saying, ‘Oh, what’s this.’ I said, ‘I thought we’d watch it,’ and my mum said: ‘Oh, I don’t mind gay people, but I don’t want to see them.’”

He is quick to emphasise that “that was what everyone thought”, and says his mother no longer takes the same view.

But he adds: “That was a huge thing for me, because I thought ‘OK, I can’t come out, my family won’t accept me’.

“I didn’t come out to my family until I was 27.”

He had girlfriends. “But I always knew this was a lie. And for me, I don’t want any child to go through that, because I lied to my family, my friends, I lied to all my loved ones, and I knew I was lying – and to those girls I was going out with, some of them for a couple of years.

“This whole thing about hiding yourself – I don’t want any child to have to hide who they are.”

Learning from his mistakes

The seeds of today’s No Outsiders programme lie in a project run by the University of Sunderland between 2006 and 2008, which researched how to talk about sexualities in primary school, and which Moffat was a part of.

He wrote a resource called Challenging Homophobia in School Using Picture Books and used it in his school in Coventry and for “little bits of training here and there”.

He wanted to work out how to do similar work in a more diverse area, so he went to a school in Newton, Birmingham.

He is frank about the mistakes he made there.

“It’s a lesson to be learned, because I didn’t get governor approval, I didn’t get parental engagement, and it wasn’t whole school – I just did it myself, with a couple of cool friends in Year 5 and 6, who dropped lessons in here and there.”

A letter of complaint arrived from a Christian parent and soon, the concern spread to Muslim families. His headteacher endured a public meeting she described as her worst in 30 years of headship.

He told her he would leave and found another job. When the press got wind of it, the story became “gay teacher resigns after Muslim protest”.

His new school was Parkfield.

“I wanted to go to a school where I thought I might meet the same challenges, so I wanted to go to a school where I knew it was mainly Muslim parents, because I wanted to work with the parents this time and I wanted to work out how you can teach equality lessons about everybody.”

He scrapped Challenging Homophobia, widened the programme to cover all equalities, and held 11 meetings with parents before rolling out No Outsiders.

“We’ve had four years of No Outsiders working superbly without a whisper of complaint. Literally not a whisper.

“In that time, we have had 29 parent workshops where we had parents coming in to show a No Outsiders lesson and to learn together, and that’s how we’ve moved forward.”

'There's nothing to do with sex education'

After all that time, why the controversy now? Moffat is clear: “I think it was hijacked, actually.”

He cites the timing of the government’s plans, finally approved this week, to update relationships and sex education for the first time in almost two decades.

“Someone made the link very early on in December from No Outsiders to sex education, and it’s not sex education. We have always been very clear on that.

“There’s nothing to do with sex in No Outsiders. There’s nothing about bedrooms, there’s nothing about how babies are made.”

'I want to be the teacher they can talk to'

Moffat didn't grow up wanting to teach, but knew he wanted to work with children.

He only lasted nine weeks in a job in children’s home – “It was just dreadful, and I thought oh my God, I can’t do this” – before becoming a youth worker.

“A lot of those young people had been excluded from school, or had bad experiences in school, and I thought that if I was a teacher, I could work with them earlier on to maybe stop that.

“I thought if I can work in primary and inspire them, and really try to work out what’s failing for them in school – I want to be the teacher they can talk to and make a difference.”

'Everyone's welcome in our class'

Amid all the controversy, what are the No Outsiders lessons themselves actually like?

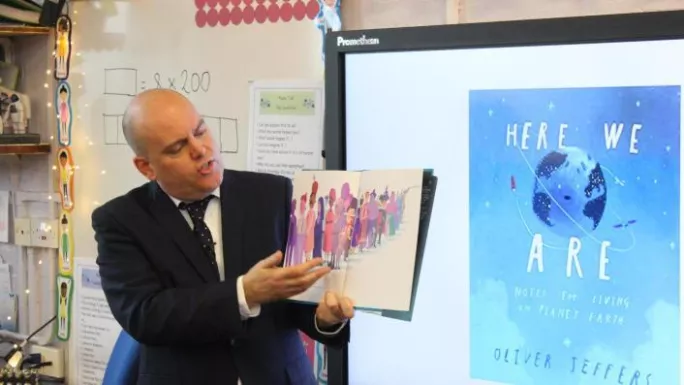

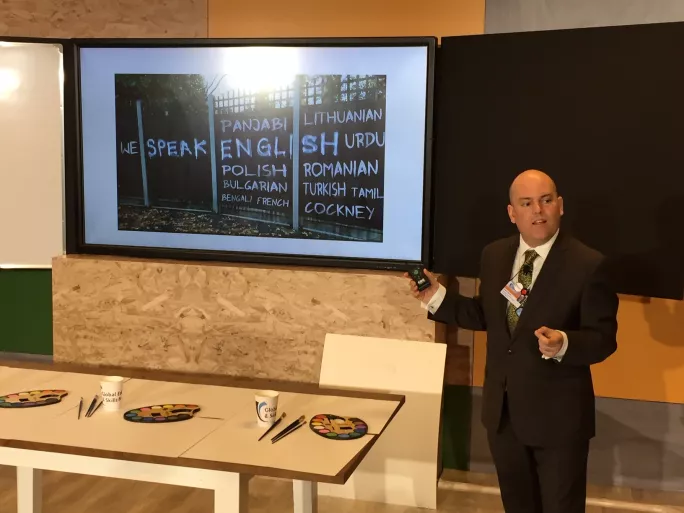

At the Global Education and Skills Forum in Dubai last weekend, where the Global Teacher Prize final took place, Moffat gave a demonstration lesson.

It was engaging, with Moffat skilfully making use a picture of a piece of racist graffiti to encourage pupils to discuss the issue of diversity and acceptance. In another activity, members of the class were given the task of learning something new from one of their peers.

In a talk summing up the lesson, Moffat said we have to “teach children to love diversity” to counter the voices they might hear that are anti-diversity.

“What makes our class great is that we can have different hair, different skin, freckles, blue eyes, brown eyes, different religions, we can wear headscarves, we can have different languages, different families. Everyone’s welcome in our class, and that’s what makes our class a brilliant class to be in. We all belong,” he concluded.

Children were chanting 'Get Mr Moffat out'

So what, then, has it been like to be at the heart of a controversy that has seen questions raised in Parliament, debates on TV, and reports that the protests could spread across a series of cities?

Although Moffat displays the poker face he says he developed as a youth worker, it is clear it has had an effect on him.

Of some of his pupils joining the demonstrations, he says: “It’s very hurtful. I think the worst part for me was when adults who weren’t actually parents were getting children to chant 'Get Mr Moffat out.' Now that was awful.”

The school has paid for him to have counselling.

But he also sees the positives, welcoming the debate it has sparked, and even the children protesting: “I mean, you know, it’s hard at the same time – I wish they were protesting about something else – but it’s a democracy. It’s a great lesson for them, and we’ve just got to as a school manage it now.”

'My goodness, I'm going back full of confidence'

What’s next?

He says he has “had times when I’ve thought ‘I can’t go on, it’s too difficult’” and wondered if he should leave Parkfield.

But the Global Education and Skills Forum came at exactly the right time for him.

“One person who’s a headteacher said to me: ‘You don’t know the impact you’re having on education in Britain today.’ Some things really get you in the heart.

“My goodness, I’m going back full of confidence.”

At the Global Teacher Prize ceremony itself, which saw Kenyan nominee Peter Tabichi emerge victorious, Hollywood star Hugh Jackman praised Moffat in front of dignitaries and world leaders including Prince Edward.

After praising Moffat's sartorial elegance, the X-Men and Greatest Showman actor told him: “You teach kids to be proud of where they come from, at the same time to be tolerant and to be accepting of people who may look different, may believe in different things and who may come from different places.”

With Moffat determined to continue his mission in the face of opponents, we must wait to see whether this story will have the perfect Hollywood ending.

CV – Andrew Moffat

Education

1976-1980: Boldmere Infants School, Sutton Coldfield

1980-1984: Boldmere Junior School, Sutton Coldfield

1984-1988: John Willmott Secondary School, Sutton Coldfield

1988-1990: Josiah Mason sixth-form college, Birmingham

1990-1993: University of Derby (BA Hons English with drama/ American Studies)

1995-1996: University of Derby (PGCE)

2000-2003: University of Birmingham (MA emotional and behavioural difficulties)

2017-present: University of Birmingham (PhD, role of schools in reducing potential for radicalisation)

Employment

1993-1997: Detached youth worker, Derby City Council

1996-1997: Class teacher, Ashbrook Infants School, Derby

1997-2000: Teacher in behaviour resource base, Thornton Junior School, Ward End, Birmingham

2001-2009: Nurture group teacher, Limbrick Wood Primary School, Tile Hill, Coventry

2004-2009: Advanced skills teacher, behaviour management and inclusion, Coventry City Council

2007-2009: Healthy schools advisor, Emotional health and well being (one day per week) Coventry City Council

2009-2014: Assistant headteacher / manager of behaviour resource base Chilwell Croft Academy, Newtown, Birmingham

2014-present: Assistant headteacher/ pastoral care, Parkfield Community School, Saltley, Birmingham

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters