- Home

- If you didn’t get the belt, you can thank my mum

If you didn’t get the belt, you can thank my mum

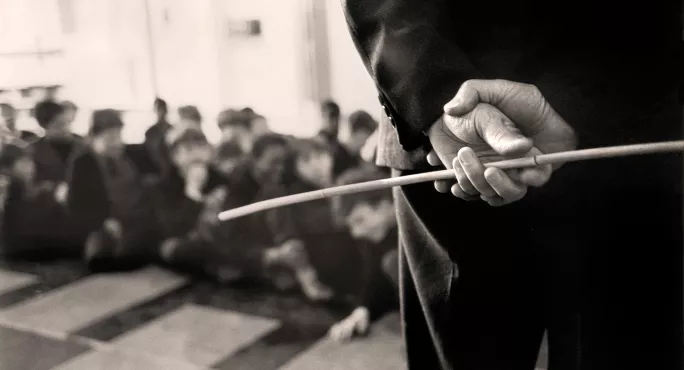

What do the 1970s remind you of? Disco, strikes, prodigious hair, perhaps the colour brown. What about state-approved weapons for assaulting children and institutionalised ritual physical abuse? If you’re under 42, then the chances are those last ones won’t have occurred to you. Here’s why.

My mum gave birth to my big brother, Gordon, when she was 27. After some heartbreaking miscarriages, I came along when she was 31. Given the rest of the story, I’m stating the blindingly obvious: we were very well loved.

My parents’ memories of their school days -like those of a lot of people - were far from those of a loving, caring education system that put the child first. Rather, they remembered the brutalising effect of being hit and humiliated repeatedly, arbitrarily, sometimes day after day, often for getting something wrong and - on one traumatic occasion - just for recovering from serious illness.

The euphemism for this is “corporal punishment” and in Scotland its formal modes ranged from a ruler across the knuckles to a spanking, but normally a heavy leather strap. The design of the strap was standardised and sanctioned by education authorities; its use regulated by formal centralised guidance.

The use of corporal punishment was ingrained in teaching. New teachers were inculcated into using physical punishment as part of their classroom routine by their peers and older colleagues - whether they wanted to or not.

Teachers who didn’t use corporal punishment were regarded as odd

In the 1970s, it was generally acknowledged that corporal punishment should be abolished at some point, but, pending its abolition, teachers were expected to use it. Those who didn’t were regarded as odd.

So when it came time for Gordon to go to school, my mum wanted to be sure we would be as safe at school as we were at home. She asked the school for an assurance that Gordon wouldn’t be hit. The school said that this was impossible.

It’s difficult to convey now, but in those pre-industrial dispute days schools really were a focal point for the local community. In Scotland, civic society revered teachers, headteachers even more so. You didn’t dare challenge a teacher when you were a pupil: you wouldn’t dream of it once you were a parent. So to ask for special treatment was to put yourself in the shoes of Oliver Twist; to put yourself above others and wait to be slapped down.

My mum asked the local education authority if it would ensure that my brother wouldn’t be hit. It couldn’t. She asked councillors and MPs, but they were unable to help. The government was not interested and held the same view as the education authority: you can’t teach children without the threat and use of corporal punishment.

Taking on the system

By the time my brother was 7 and in Primary 3, he had witnessed other children getting belted. He was quite affected by it. He was afraid that the same would happen to him, and the fact that my mum had challenged the education establishment over it made that even more likely.

So what could be done about it? Although used on younger children, corporal punishment was officially permissible once a child reached the age of 8.

My mum decided that it was time to fight. The lawyers said there was no point going through the UK courts because the law was clear: it was all perfectly legal. The only court left was the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, so in 1976 that’s where she went. The case wasn’t about the system, it was just about me and Gordon. Another mum, Jane Cosans, raised legal action around the same time for her son, and the cases were joined. My mum went on point to endure the publicity. And my, there was a lot of it.

Suddenly we were infamous. Locally there were those who were supportive, some of whom were teachers, but generally people were openly hostile to the idea that someone might challenge corporal punishment and, heaven forfend, might get it removed from schools altogether.

Some people stopped talking to us. One teacher who lived at the bottom of our street never spoke another word to us.

We had to be on our best behaviour because people were itching to say that not hitting made for bad children

We had the media camped outside our door, with all the joy that brings. As kids, we always had to be on our best behaviour because people were itching to say that not hitting children made for bad children. We had graffiti daubed on our front door, made to look like a child’s writing but unmistakably that of an adult.

One night, the evening news came on and there was an item comprising a whole class of children singing a song that they’d composed about “Ban the Belt”. They were singing about how they wanted to keep it, and all I could think was, “How did they manage to compose a song by themselves on school time - and how did the news find out about it?” Thanks to that we became known as “Ban the Belt”, and having that yelled at you on the way home from school quickly becomes tiresome.

The brick through the living-room window was almost a cliché. Finishing a phone call and then hearing a recording of it played back down the phone because you didn’t hang up quickly, just plain sinister.

My parents did their best to shield us from it all, but you can’t hide stress and during the 1980s I was aware of my mum being under a lot of it. She was juggling raising two young boys, a part-time job and the case. In 1982, she had a stroke at the age of 40. The court issued its judgment the same year. Six years after the initial application.

Children spared from abuse

I remember being so impressed that my mum was on television, seeing her going into the courthouse in Strasbourg.

She brought toys back from France for us. I was 8 and aware that something big had happened and that we wouldn’t be getting hit at school, but not much beyond that and the impressive size of my toy lorry. I was really proud of my mum and what she did for Gordon, for me. As the years have passed, I’ve only become more impressed.

The government tried to find ways to keep corporal punishment, but ultimately it realised that the only way to provide the education the court said we were entitled to was to remove it from the whole system. So the school year began in 1987 with corporal punishment suddenly banned from all state schools overnight, as if it had never existed.

My mum died two years later at the age of 47. She would have been deliriously happy to have met her grandchildren and seen how secure and happy they are at school, that education could be so different so quickly. If you were born after 1979, this has been a history lesson. But not ancient history: it was October 2000 before corporal punishment was banned from all schools in Scotland.

Andrew Campbell is the son of the late Grace Campbell, who led the legal case against corporal punishment in British schools in the 1970s and 1980s. The views expressed here are his own

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters