- Home

- The kids aren’t all right: the rise of the snowflake

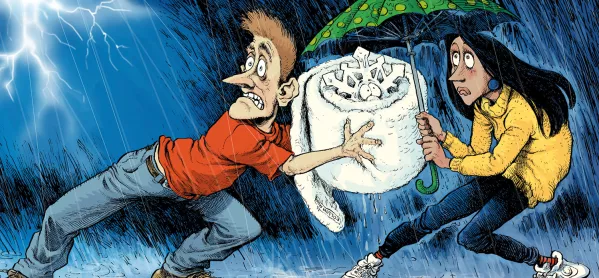

The kids aren’t all right: the rise of the snowflake

Ariana Grande’s One Love Manchester concert, organised a mere fortnight after a terrorist outrage had maimed and killed many attendees at her Manchester Arena concert on 22 May, was rightly celebrated as an inspirational act of defiance against Islamist nihilism. Many of the pop star’s young fans who had been at the original concert attended, saying they wanted to “stay strong and carry on”.

There was concern that attending a music event featuring the same singer, with all the paraphernalia associated with a concert - flashing lights, loud noises, even a confetti “explosion” - might trigger bad memories, even post-traumatic stress disorder, among attendees. But child psychologists concluded that, no, this was the right thing to do for these young people: not to shy away, be fearful.

This contrasts with broader cultural practices deployed by increasing numbers of young people, who claim that the most trivial events/words can trigger trauma. Take the fashion for demanding that advance warnings are issued before lectures containing “content that may trigger the onset of post-traumatic stress disorder”, so that students can skip class if they fear teaching materials might be bad for their mental health.

Trigger warnings are seen as necessary for any lectures that might contain descriptions of sexual abuse, self-harm, misogyny, bullying or body shaming. This would mean viewing the whole of literature as a threatening enterprise and explains why trigger warnings have been issued on texts such as The Great Gatsby.

One student theatre director wrote recently that he had to leave a performance of Peter Grimes “as a result of unexpectedly discomforting scenes of sexual grooming and assault between Peter and a younger man”, and demanded that “ticket holders are made aware of unsettling scenes before being seated”.

Harvard professor Jeannie Suk, who has warned that US universities are dropping rape law from syllabuses because teaching it is “not worth the risk of discomforting students”, explains one reason for this: “Many students seem to equate the risk of traumatic injury incurred while discussing sexual misconduct as analogous to sexual assault itself.”

I think she’s right. The notion that words and speech are interchangeable with physical violence, and can trigger trauma, lies at the heart of many of today’s university free-speech controversies. So attempts to no-platform feminist icon Germaine Greer were justified by equating her alleged transphobic attitudes to acts of violence and psychological harm.

‘Thin-skinned wimps’?

Such trends have led to the young being branded thin-skinned wimps. The derogatory label Generation Snowflake, which entered the Collins English Dictionary in November 2016, is defined as “young adults, viewed as being less resilient and more prone to offence than previous generations”. But while this trend is easy to lampoon, generational fragility is a real phenomenon. The shift over recent years is regressive for young people themselves.

Consider safe-space policies, now ubiquitous on college campuses. The safety demanded is not protection from physical harm, such as terrorism or sexual violence. The NUS students’ union’s definition of safe spaces calls for a university campus to be: “An accessible environment in which every student feels comfortable and safe and can get involved free from intimidation or judgement.” Let alone the educational catastrophe of higher education “free from judgement”, or the dangers to open debate of echo-chamber silos where only received opinion is allowed, the key cultural shift is the demand for safety.

Historically, going away to college is associated with risk-taking which, while a wee bit dangerous, allows the young to embark on the exhilarating journey to adulthood. Yet now, when teens should be on the brink of life’s great adventure, they aspire to safety.

I don’t blame the young. The theme of my book ‘I Find that Offensive!’ is that such timidity and its attendant illiberal censorship is our fault. When students arrive at university, they are preloaded with therapeutic concepts and drained of resilience. Where did they learn to be oversensitive about the potential damage of words, that speech causes psychological harm?

One educational culprit is the anti-bullying industry. The expanded definition of bullying includes: teasing, gestures, spreading rumours, name-calling and exclusion from friendship groups. This has led to the rebranding of petty unpleasantness as something more sinister.

Sarah Brennan, chief executive of children’s mental health and wellbeing charity YoungMinds, has called such bullying “devastating”, adding “it can lead to years of pain and suffering”. But telling kids that name-calling can lead to years of pain seems an irresponsible stirring up of anxieties. Surely such sensationalist messaging about the traumatic effects of bullying encourages the young to overreact to the vicissitudes of life?

Why are we surprised by demands for safe spaces at 18-plus? After all, in the name of keeping kids secure, educational and social policy goes to ludicrous lengths to eliminate risk. There are panics about everything from skin cancer (don’t let the kids play out in the sun) to the obesity time bomb (declare sugar to be crack cocaine for children).

Health and safety regulations mean playground activities are overpoliced, while “roaming distance” (how far children play from home) has decreased 90 per cent in 30 years. The invidious narrative of paedophiles around every corner has led to overzealous CRB checks and parents banned from taking photos of their own kids at school swimming galas. This teaches the young to be distrustful, ensuring the jargon of safety becomes their second language.

Similarly, when children as young as 6 self-report that they are suffering “anxiety” and “trauma”, and have “damaged self-esteem”, we can be sure they don’t pick up such diagnostic vocabulary in the playground, but from us.

A recent Tes article illustrates the problem. In it, the reformed exam system is said to be “creating a generation of damaged children” (bit.ly/GCSEPanic). Surely more damaging to how teenagers might view imminent exams is the declaration that “This is not education. It’s torture.” But it isn’t torture, is it? Such hyperbole incites the young to see themselves as too fragile to not only cope with maths GCSEs, but life in general.

If 21-year-old Ariana Grande can encourage young people to stare down the horror of terrorism, then surely SAS and curriculum changes are an easy foe. There’s no need for there to be future Generation Snowflakes if we - the grown-ups - stop transposing our own fearful preoccupations on to the young.

Claire Fox is director of the Institute of Ideas and a former FE teacher. She tweets as @Fox_Claire

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters