- Home

- ‘Picture books aren’t just for primary’ - a Q&A with award-winning author Chris Haughton

‘Picture books aren’t just for primary’ - a Q&A with award-winning author Chris Haughton

Chris Haughton can comfortably be considered a star in the world of picture books. The illustrator and author’s awards and nominations include the Association of Illustrators prize, the Booktrust’s best new illustration and the Irish book award. To mark the Tes literacy special issue in our 11 August issue, we caught up with him to discuss the role of picture books in schools.

Tes: Do you think picture books have a place in the classroom?

Chris Haughton: Yes, I do. I worked with the Centre for Literature in Primary Education (CLPE) on a programme called the Power of Pictures. We asked the children to look at the pictures and then try to infer what was going on from them. Even the really young children were able to do it.

I think that’s an important skill to have today, because a lot of the media we’re presented with is based around images, and we have to decode that. Sometimes it’s better for children to find their own meaning in the pictures instead of just being told what’s happening through the words.

Tes: Some would argue picture books would only be appropriate for the youngest children in school, not for those in the later stages of primary or secondary. What is your view?

CH: They can definitely be used in classrooms with older children as well. At CLPE we had a class of teenagers. We gave them my book Shh! We Have a Plan with the text removed, and we asked them ‘What’s going on here?’

The range of answers was really exciting. They were really discussing it and it was a really lively debate; it would be a class that I would love to be in.

We were trying to guess what was going on, what each character was feeling from different characters’ viewpoints and it’s amazing how much different stuff each child came up with - I wrote the book and I was amazed by how much they were reading into it, drawing from those one or two images.

Finally, we read the story and it was very satisfying to see everyone finding out if they were right or not. It was brilliant and so entertaining because everyone wanted to participate and was excited to give their opinions. It’s a really good way to get into analysing books.

Tes: Despite this experience being shared by a number of teachers who do use picture books, there seems to be a lot of hostility from some teachers to picture books, particularly those in secondary. Why do you think that is?

CH: In France, graphic novels are really popular. We don’t really have that here. In the UK and English speaking countries I think we tend to see pictures and picture books as “low art”. It’s seen as cheap, comic-book sort of stuff.

I have one friend in France who writes picture books and she noticed that in England and America especially there is a very conservative view about what should be allowed in a picture book.

She has one book where a butcher is pointing a knife at a little girl. There’s nothing threatening going on, he’s just telling her off. It’s been published in 15 languages in different countries no problem, but in the UK she couldn’t publish it.

This is because picture books are seen as just a stepping stone towards literature. They are aimed towards the very young. If you’re viewing picture books as for the very young who can’t read yet, then you can’t have a knife in it.

I think this can have a knock-on effect because if there are young kids who are seeing these sanitised picture books where there’s no violence and just rainbows and bunnies, then they might think books aren’t for them.

Especially for young boys, because they might think they’d rather play a video game or watch cartoons, because they’re not so sanitised. So I think that might be why older children aren’t so interested in picture books, because they don’t always reflect the real world.

Tes:

CH: I think everyone can enjoy picture books. There are some now which are very sophisticated and include dark humour and they can be cool. You don’t have to remove pictures for it to be an adult book. It’s the content, the story and the humour that appeals to people.

I try to make my books entertaining for myself, as well for young children. There is a type of humour that can be very funny for a two-year-old and also for a 90-year-old - that slapstick and very simple clowning which, if it’s done right, can be entertaining no matter what age you are.

Tes: Does it frustrate you that people view picture books as simplistic?

CH: Well, I always try and communicate things in the simplest way so that everyone can understand and everyone can get it. But all of my books have a quote, which I choose at the end of the book, where there’s some kind of moral message. I’d like to think that all of the dilemmas in my books would be understandable to the youngest child or to an adult.

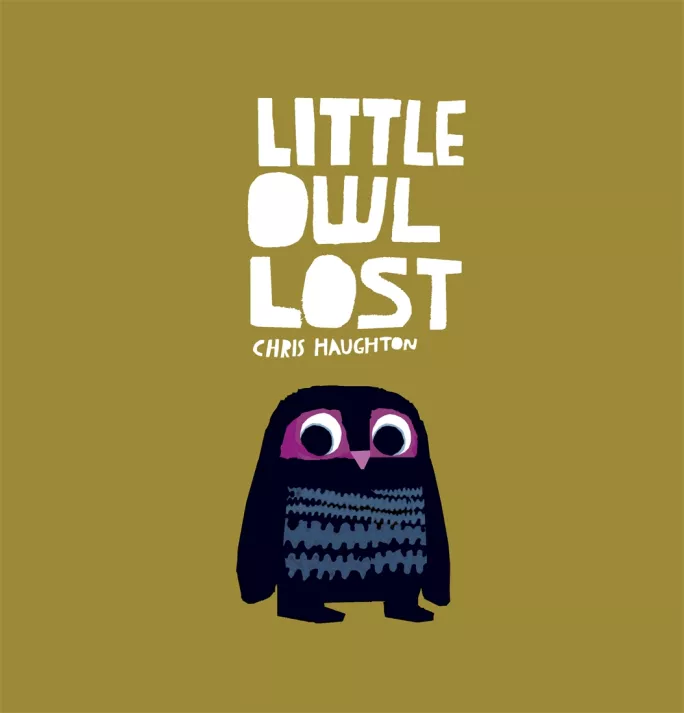

In one book I have a quote from Robinson Crusoe. The book is about an owl feeling lost. We can all identify with that feeling whether you’re a great figure in literature, or you’re a lost owl.

Chris Haughton’s latest book is Goodnight Everyone. He is also releasing a VR app with Red Rabbit called Little Earth, which aims to teach children about the environment.

The Tes literacy special issue is released on 11 August and includes articles on why memorisation of poetry boosts understanding, the guided reading versus whole class reading war, how to run creative writing projects in KS3 and two literacy leads give their mission statements for the next 12 months.

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters