Giving power to pupils is the right approach

The Scottish government’s governance review - for which consultation closed a fortnight ago - asks a number of important questions about how Scottish education is organised and run, and invited responses from across the sector.

Its foreword suggests that “successful systems [are] those where governance and accountability are inclusive, adaptable and flexible”. The consultation sought views from teachers, parents, local authorities - as well as from children and young people themselves. I regard the most important question to be, “How can children [and others] play a stronger role in school life? What actions should be taken to support this?”

I believe the consultation is most timely, as I sense something significant happening within our education system, in respect of the rights of children and young people. When I started as commissioner in 2009, I received lots of advice. Some warned against engaging too extensively with schools because they were - apparently - hostile to promoting the rights of their pupils. My experience since then has not only confounded this view, but also confirmed my belief that schools and education are central to the better realisation of the rights of children and young people.

I have visited more than 200 schools, and I have personal experience of great rights-based work in school settings. Today, the question most frequently being asked in respect of children’s rights is not “Why?” but rather “How can we do better?”

One indication of the distance travelled is that, in the UK, Scotland currently has the highest proportion of schools signed up to the Unicef programme of Rights Respecting Schools.

Nevertheless, we have a very long way to go to be certain that children and young people are experiencing all their rights in school settings. If the government is serious about school governance, then including children and young people in those processes is vital, and I welcome the opportunity to influence the government’s thinking on this aspect of the review.

However, there is another, equally important reason for improving the role of children and young people in school governance. The review specifically highlights a “strong and shared commitment” to equity and raising attainment, with a particular focus on “closing the poverty-related attainment gap”.

Student participation

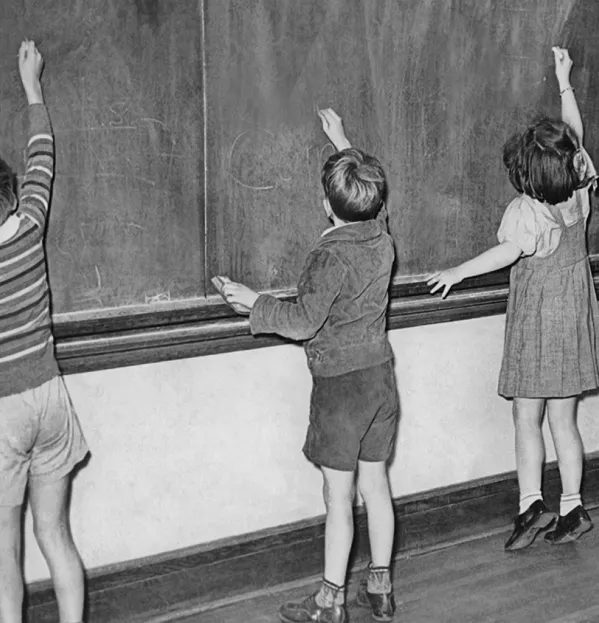

Various articles of the UNCRC (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child) exhort governments to provide education in a way that enables the child to express his or her views freely and to participate in school life. As Unicef puts it: “The participation of children in school life, the creation of school communities and student councils, peer education and peer counselling, and the involvement of children in school disciplinary proceedings should be promoted as part of the process of learning and experiencing the realisation of rights.”

Schools and education are central to the better realisation of the rights of children and young people

My office has evidence that actively seeking the views of children and young people and encouraging them to take part in decision-making in schools is a common feature of schools that are performing outstandingly well, and can directly help to reduce the attainment gap.

Two years ago my office conducted research on pupil attainment. It specifically examined why some schools were doing remarkably well while serving largely poor socio-economic areas. The research focused entirely on the pupils’ perspective, rather than on the adults in their school, and explored how they described the links between different kinds of participation and “doing well”. This included doing well in both attainment (such as test scores, examination grades and formal qualifications) and achievement (wider success and development).

In schools that were doing well, we found that there was a shared understanding among pupils and staff of the value of participation across all areas of school life, from planning for the formal curriculum and the informal curriculum, to having a place on decision-making groups, and participating in other situations of informal contact among peers and adults.

Rich rewards

Put simply, for young people to develop and do well, it is necessary to value and enable their participation.

Applied rigorously, this concept is about much more than just having a say in decision-making - it’s about schools, and the education system in Scotland as a whole, taking a broad, rights-based approach.

Our research suggests that rights-based experiences and a good education cannot be easily separated; they are intimately connected in the lives of the young people.

Schools can - and should - robustly and confidently integrate rights-based practice across every aspect of school life, as part of an agenda of raising attainment and achievement. Staff could work alongside pupils conducting health and wellbeing surveys, and have a shared responsibility for implementing any findings. Pupil councils could be supported to form representative bodies at local authority level. Peer mediation could be used to assist in early resolution of conflict within the school.

These are all examples that are occurring right now, but they are nuggets of good practice rather than the norm. Beyond this, schools could engage pupils in planning and assessing improvement, staff recruitment, evaluation and inspection - as participatory approaches become more fully developed.

A rights-led approach to education is a cost-effective measure to improve outcomes for children, as quality relationships and developing participatory approaches in schools cost little, yet deliver rich rewards.

The UN’s Committee on the Rights of the Child challenged the UK government and devolved administrations to ensure that all children and young people are heard - in all decisions that will affect them. The voices of young people should act as a touchstone, to ensure that we do indeed meet this international obligation.

Tam Baillie is the children and young people’s commissioner in Scotland

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters