On social media, everybody can hear students’ exam screams

Teenagers across the country have been replacing their “crying” and “weary” emojis on social media with “party poppers” this week as the GCSE and A-level exams finally came to a close.

The exam season can be a stressful time for all those involved - and if the Twittersphere is anything to go by, the blood pressure levels of pupils, teachers and parents have risen over the past six weeks.

The first exams in the new tougher GCSEs in maths and English this year - as well as 13 new linear A-levels - have placed a “guinea pig” cohort of pupils under even more pressure than usual.

And a series of widely publicised exam paper errors - and, in two recent cases, alleged leaks - appear to have made the summer harder still.

But has this exam season really been a particularly bad one for exam boards? Or has widespread use of social media just given pupils a larger platform to raise commonplace anxieties?

When pupils leave the exam hall they no longer offload to just a few friends outside. Now they can set up online petitions to lower grade boundaries, and increasingly flock to social media to vent their frustrations about difficult questions or exam errors.

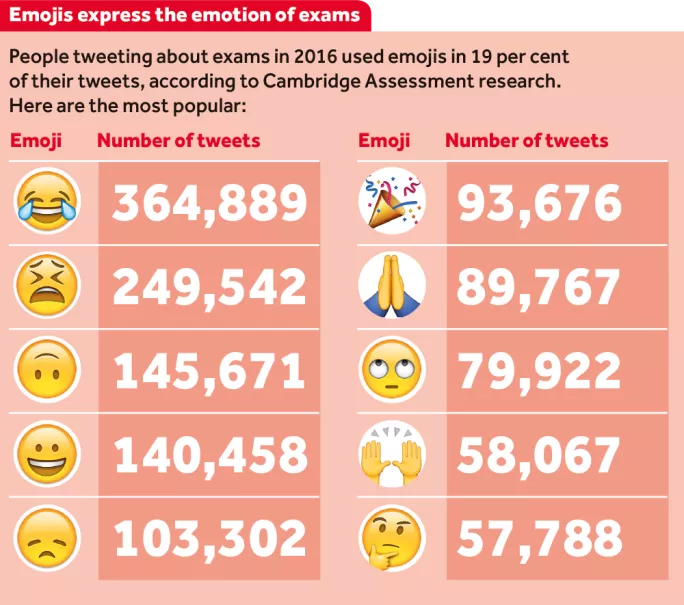

That means instant access to and interaction with potentially tens of thousands of candidates all experiencing the same frustrations. Many of these exam “post-mortems” - as Simon Lebus, chief executive of Cambridge Assessment, calls them - can quickly trend on Twitter under hashtags, especially if many pupils have taken the exam.

So what might have been limited to a few isolated grumbles a decade ago can now rapidly explode into a major social media incident. Last month, for example, an AQA GCSE biology paper received a lot of attention on social media after pupils were asked why Charles Darwin was drawn as a monkey in cartoons in the 1870s.

The exam board received 3,000 tweets about the question - despite there being no factual error. Kunal Gandhi, AQA’s social media manager, says: “The vast majority of tweets aren’t actually about errors. It’s just students mocking questions that they found difficult or amusing.”

And much of the post-exam online conversation does appear to revolve around pupils posting memes and gifs on Twitter to try and outdo each other.

‘Unacceptable’ error

However, the microblogging site has been used to flag up genuine concerns and complaints with exam boards, like errors on papers. OCR had to apologise three times in just over a fortnight this summer after making mistakes in GCSE and A-level exam papers.

The first error in the new GCSE English literature paper - which wrongly implied that Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet was not a Capulet - led to an intervention from Ofqual. The exams regulator described the mistake as “unacceptable” and said it would be “closely monitoring” OCR’s investigation into how the error happened.

OCR isn’t the only exam board to find itself in hot water this exam season. AQA had to apologise when an unanswerable question was included in its A-level chemistry paper. And just last week, investigations were launched into alleged leaks of questions from two Edexcel A-level papers.

However, exam boards and assessment experts insist that the number of mistakes within tests have not increased this year. “We are seeing a broadly consistent picture with previous years,” a spokesperson for Pearson, which runs Edexcel, says.

In fact, prominent assessment expert Robert Coe, director of Durham University’s Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, suggests that the number of errors could have dropped because of greater awareness.

“It kind of raises the stakes for [the exam boards] that mistakes they make are not forgiven or ignored in the way that they might have been in the past,” he says.

“Now you absolutely get roasted if there are any at all.”

Tim Oates, group director of assessment research and development at Cambridge Assessment, agrees that the stakes are higher. “We are seeing much more reaction to the errors that do arise, as a result of immediate communication using social media,” he says.

The use of social media also presented challenges for the Department for Education during this year’s primary Sats. Because pupils who are ill can take the test up to a week later, any publicising of questions immediately after the paper is first taken is a serious issue.

This summer the DfE sent a series of tweets to parents asking them to remove posts from Twitter which included details about questions. But some refused to delete their widely shared comments, citing their complete opposition to the testing regime.

So social media can dramatically increase the workload of the DfE, exam boards and exams regulator Ofqual. According to the AQA board, staff now typically look through tens of thousands of tweets to identify genuine questions and concerns.

And the messages that pupils post can end up being very influential, particularly when taken collectively. Speaking to Tes before the exams begun, Sally Collier, chief regulator of Ofqual, acknowledged that social media is one of the platforms the watchdog looks at when judging whether to intervene over a paper. “I think it is a judgement call that I have to make on a range of indicators,” she says. “You might have a volume on social media, you might have a risk perhaps that we were monitoring in an exam board, you may have previous instances of this particular qualification.”

But social media can also give pupils easier access to exam boards if they are seeking reassurance. And post-exam dissections can immediately highlight concerns about papers that do need addressing.

Pupil power

This month, pupils and teachers took to social media to complain after a formula was not included in OCR’s A-level biology paper, despite the exam board’s guidance to schools saying that it would be.

“Social media is a valuable tool,” an OCR spokesperson admits. “Part of our job is to use social media as one of a range of tools that help us recognise when there is a real issue that will need to be addressed in marking or grading to ensure fairness - and when, as in most cases, there is not.”

Often exam students do go on to social media simply to let off steam about unexpected or difficult questions.

In 2015 a supposedly near-impossible exam question in an Edexcel GCSE maths paper - the now infamous “Hannah’s sweets” question - became an internet phenomenon following a Twitter storm of derision from frustrated pupils.

But the question didn’t involve an error and, experts say, it wasn’t “actually that difficult” for pupils who were able to join up the various topics they had been taught in maths.

Some worry that this kind of Twitter storm can become damaging. Last year, Coe suggested that a fear of a social media backlash had prevented exam boards from setting harder questions and had led to papers that were too predictable (see bit.ly/SweetsQ).

But the exam boards insist that complaints on social media do not influence their decisions when creating papers. This month Gandhi stressed that exam papers had to distinguish between candidates of different abilities, and said that AQA would not cave in to online criticism.

“It’s our job to create qualifications that act as the keys to help young people unlock the future,” he wrote in an article for the i newspaper. “For these qualifications to be worth the paper they’re written on, the exams have to be challenging - no matter what people say about us on Twitter.”

And at Edexcel, a spokesperson says that one of its biggest challenges with social media is ensuring that a balance is struck and it “does not influence our attitude to exams”.

That is not the only fear. Research from Cambridge Assessment argues that because Twitter now shapes media coverage, it may also “affect the general public’s view of exams and their standards”.

There is evidence to back up concerns that social media and online platforms have damaged the public perception of exams. A recent poll, carried out by The Student Room website, found that more than four-fifths (86 per cent) of pupils have lost some faith in the system after this year’s exam errors.

And it is not only pupils and parents expressing concern about the system - teachers are, too. “[They] are very exposed on this because they care about what results their kids get,” says Coe. “Also, some of their jobs could be on the line and their pay could be on the line and their reputation could be on the line. I think that pressure has increased.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters