Social mobility is not the point of education

Read the following quotes and - without thinking for too long - then say out loud what you think schools are for.

“Education is at the core of social mobility.”

“Teachers - the experts in driving social mobility.”

“A welcome consensus has begun to emerge that schools must be engines of social mobility.”

The first two quotes are from education secretary Justine Greening. The third is from schools minister Nick Gibb. Do you think the primary purpose of education is to help young people get jobs and fix the economy? I absolutely do not. The problem is that I seem to be in an increasing minority. Everywhere I look we are told the core aim of schools is to drive social mobility. The Sutton Trust bombard us with this message. Ofsted repeat it, mantra-like. Teach First have as their strapline: “Together we can drive action for change on social mobility”.

Regrettably, even our teaching unions now seem to accept social mobility and social justice as the aim of education.

Cultivate curiosity

Those of us who still believe unequivocally that a school should be about the cultivation of intellectual curiosity and the transmission of knowledge need to stand up and be counted. Schools are being redefined into centres of social engineering, which is antithetical to liberal, subject-based education.

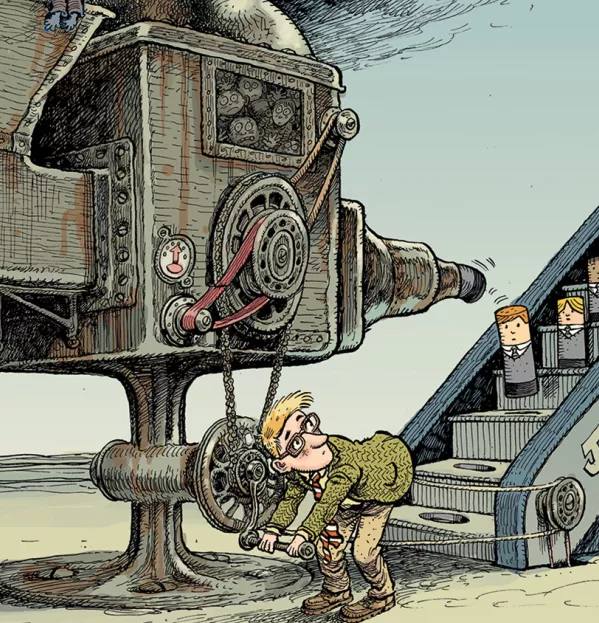

In recent years, under successive governments, education has been transformed into an instrument of public policy, a means of achieving objectives that are entirely external to learning and a love of knowledge.

Hardly a day goes by without a leading politician - or, worse still, an employers’ organisation - exhorting schools to better prepare our students for the workplace, as though the aims of a school should be directly subordinate to that of CBI or Britain plc.

It’s as if schools have been detached from our educational moorings and we are no longer sure what we stand for as we lose the confidence to defend the pursuit and love of subject knowledge for its own sake.

Into this vacuum, we have allowed social mobility to be seen as the moral purpose of education rather than an informal byproduct of it. Hence, schools increasingly focus on finding ways for students to improve their employability and earning potential rather than their minds.

When Ofsted visit a school, we are now expected to have detailed figures not only on university destinations but also the jobs our students go onto. Schools - to be more precise, teachers - are now held responsibility for social responsibility or lack of it.

This is, of course, nonsense. If you want to help disadvantaged young people get jobs, fix the economy. Don’t expect schools to solve a non-educational problem. To be blunt, the politics of social justice should be left outside the school gate.

If you want to educate young people, teach them Shakespeare, Kant or Pythagoras. If you want to fight for social justice, a radical party or overthrow capitalism, that is your right, but don’t confuse such goals with teaching.

A sense of disorientation exists among many teachers today. It is brought about by alienation and a sense of estrangement from the subjects and vocation we love. The more non-educational and instrumentalist imperatives are imported into education, the more confused and disorientated we teachers become about our core mission.

If our professional bodies and unions won’t stand up against the current bastardisation of education into little more than a jobtraining scheme, then we need to organise and do it ourselves. Let’s fight a culture war against those politicians and organisations who are reducing our nation’s schools to little more than on-the-job training.

Education should not be thought of as an engine of social mobility because to do so degrades teaching, distorts the role of teachers and places an undue burden on schools.

This distortion also involves the current obsession with data and mass teaching to the test in order to comply with the tick-box and target culture.

The data-tracking obsessed teaching currently in vogue is predicated on the idea that we have a moral obligation to “improve the life chances” of students in the job market.

Let me be clear: my job is to teach my students and teach them well. To inspire them. To instil in them a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world. To convey the seriousness of the subject and in doing so to help turn them into free-thinking autonomous young citizens of the world who value the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake.

That is my responsibility and I take it seriously. What happens after young people leave school is a political, social, economic and personal question, not an educational one. Let teachers teach and let politicians fix the job market.

Kevin Rooney is an author and head of social science at Queens’ School in Bushey, Hertfordshire

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters