Trust in charities to find the right way forward

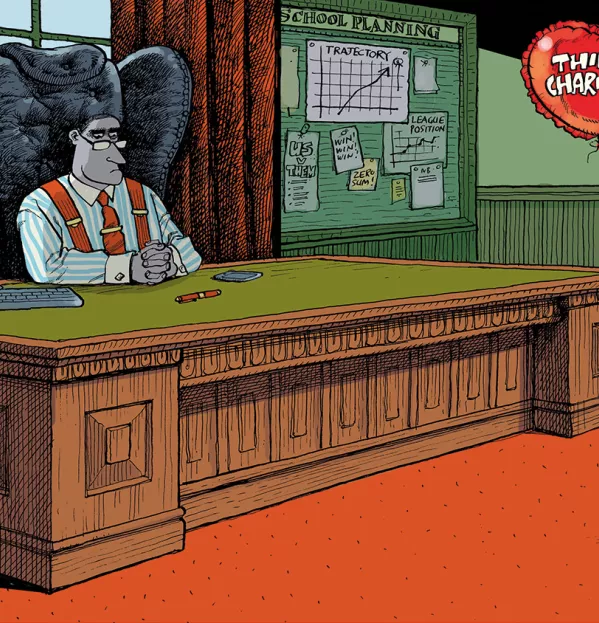

For too long, those in charge of academies, multi-academy trusts and wider government thinking have talked about the lessons that education can learn from the private sector and the business community.

But with many, many questions hanging over the academies system and its governance - think salaries, related-party transactions and the recent collapse of the Wakefield City Academies Trust - it’s now time to rethink where the schools sector finds its inspiration.

For models of leadership for moral purpose - for outcomes with public benefit - it is time that education leaders started to look towards the charity sector. After all, most multiacademy trusts are, in fact, charities.

Balancing the books with moral purpose is the challenge for all charity CEOs. With charities held by their charitable objects to have “public benefit”, their CEOs have, for many years, been juggling reducing budgets in a competitive context where brand and marketing skills must exist alongside often highly specialised skills

That is not to say that the charity sector has everything working perfectly, but even in its errors the education sector should be able to find some lessons.

For example, the danger of the charismatic CEO, highlighted by such stories as the Kids Company debacle, has direct read-across to the concept of “superheads”.

So here are five things that education can learn from the charity sector:

1. Have a clear vision to avoid ‘mission drift’

In the charity sector, CEOs are alive to the real risk of “mission drift”: gradually abandoning the core purpose to maximise the income needed to keep the doors open.

In education there is, at present, only one key funder. Gradually, we have seen some schools drift from their own visions for their community in order to jump through the hoops of the Department for Education (which is also arbiter of the rules judging schools - a conflict of interest that doesn’t happen in the charity sector.)

Having a clear vision, mission and theory of change helps charity CEOs to avoid this drift. This is not to say that they don’t draw on a healthy dose of pragmaticism to maximise funds for their beneficiaries, but annual impact reporting against what the charity intended to do rather than what the funder wanted it to do is a vital tool in keeping honest and focused.

2. Avoid a divided sector

At a system level, the gap between the haves and have-nots in the charity sector should be a warning as to how the education system is forming. The top few charities have over 70 per cent of the charity income. Their brands are strong. They attract more funding. They can pay for more experienced staff, including fundraisers and PR teams. The gap gets wider.

Does that matter if the work is done? Increasingly, yes, as smaller charities that work with the hardest to reach and offer specialist services start to struggle. Does it mean the big charities are not doing great work? Of course not, but it does mean that they mop up support funding, PR and overall momentum.

Is something similar happening in education? Well, the largest academy chains and schools are growing both brand and budget while, at the same time, there are some concerns that they may be avoiding some of the most vulnerable learners or moving further away from community interests.

3. Users, users, users

The charity sector still hasn’t got governance and diversity completely sorted out. But at least the debate is a mature one. Charities that haven’t got user representation throughout their governance are the exception, not the norm, and are rightly frowned upon.

The fact that it was even a potential policy point that MATs and schools did not have to have parents in their governance structure made several charity colleagues raise their eyebrows. That the views of children and young people are not a feature of governance in some schools or MATs is unusual, set against the context of the wider children’s charity sector.

Even - or maybe especially - charities working with some of the most vulnerable and hard to reach children in society have processes to bring user input into service delivery and design. Within education, questions about pupil involvement in feeding back on a school’s performance or the potential for learners to get involved in sharing teaching makes for a very long evening on Twitter …

4. Value trustees (but don’t pay them)

The principle of charity is the notion of the “trust”. The trustees of the charity hold the assets of the organisation in trust for its charitable purpose. Most trustees in the charity sector are unpaid. And the sector, which includes many organisations bigger than any MAT, has regularly turned its back on paid trustees.

That is not to say that the debate doesn’t continue, and exemptions are awarded by the Charity Commission. But the notion of voluntary service rings true. Volunteers and trustees are seen as a significant resource, and the best charities invest in their recruitment and development. With no paid trustees and clear views on related-party transactions, it is easier to challenge decisions on matters such as CEO pay and value for money.

5. Think differently on income and expenditure

Most charity leaders would sleep happily at night if they started their year with 100 per cent of their funding in place. In reality, most start with much less that this and the 12 months is a juggling act to ensure that income comes in and expenditure is maintained. They have to think differently.

If a school budget is tight, it seems that the automatic response is to look at cutting staff. But for charity leaders, other models exist, and schools need to think about gradually moving towards a mixed-income model. Alumni-giving, grant funding, corporate partnerships - all are approaches being adopted by schools, and many MATs are now employing fundraisers to support this work.

Considering what assets the school can trade on is increasingly important, and, again, charities are a long way down the road of setting up commercial trading arms to generate income for their charitable activities.

Even in a system where all schools were adequately funded to provide their core work, it could be argued that income from other sources might support a degree of flexibility and innovation, and help to ensure that the school’s vision for its community might be pursued despite the agenda of the government of the day.

Charities truly haven’t got all the answers. But, lest we forget, our current state-funded education system was predicated on the work of charities. Many teachers have set up or are working in charities. More than £2 billion worth of charitable funding and over 60,000 charities are working to improve outcomes for children and young people.

Charity provides a potential new set of solutions for the schools system - one that puts moral purpose before profits.

Anita Kerwin-Nye is managing director of the London Leadership Strategy and chair of Whole School SEND

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters