Want students to recall English terminology in an exam? Draw them a picture

What was clear is that we had gaps. Pupils might be learning what similes were in Year 7, but could they recall that knowledge and use it when it came to GCSEs? Not as often as we would like.

We needed to do better at embedding key information and concepts. So, our head of English, Adam Lewis, decided to do something about it. Having helped to evaluate the approach he came up with, I wanted to share his promising results.

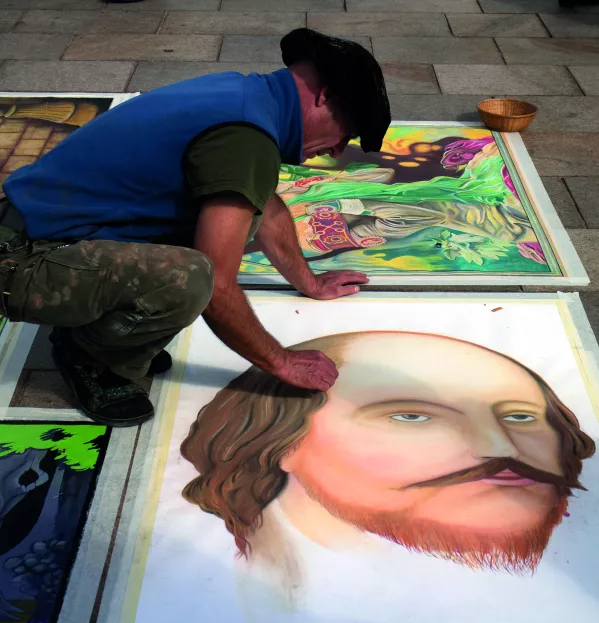

After doing research around memory and retrieval (most notably the work of Bjork and Bjork), Adam began to identify the various needs and also some possible solutions. One of those was dual coding.

Put simply, Allan Paivio’s theory is that the creation or formation of mental images aids retention and retrieval of information. So, if you can build images associated with key learning goals, the information should be more memorable because it is taken in via two channels, the verbal and the visual, and memory traces are doubled.

Although Paivio’s seminal paper is the basis for development in this area, many others have provided insights, including the Learning Scientists, and Shannon Harp and Richard Mayer.

The key learning area Adam targeted was vocabulary. We work in an area of high disadvantage and low literacy (compared with national standards), and about 50 per cent of each cohort come in with a reading age at least six months behind their chronological age. When this is matched with high levels of English as an additional language, retention of subject-specific terminology can prove an issue, especially with regards to retrieval and accurate use in assessment.

Based on his research with dual coding, we had three possible solutions:

- Provide just the subject terminology and definitions.

- Create and supply images for the group to use when learning subject terminology.

- Get pupils to create images to combine with the subject terminology.

The first option was what we had been doing already, with mixed success. Adam pondered options two and three, and opted for the latter: pupil involvement and engagement helps to provide that essential contextual connection, so it made sense to make them an active part of the process.

He decided to test out the intervention on his 28-strong class of Year 7 pupils, with an aim to embed the terminology early and trace the development of the strategy across an academic year. His control groups were, naturally, his other groups, with whom he was not using this method.

In order to implement the intervention successfully, Adam conducted a baseline test of the knowledge all his pupils had of more than 100 terms and their definitions.

Pupils in the test group were then given time in lesson to create images to supplement the terms and their definitions on flashcards (term and image on one side, definition on the other). Words ranged from simple terminology such as “poet” and “playwright” to more complex concepts such as “flashback” and “stichomythia”. Adam was keen to stress to pupils that the quality of the drawing was not important - it was the process and the image that would aid the retrieval.

Pupils were then given a follow-up test of knowledge at intervals throughout the next two terms, with a test of the terminology studied taking place roughly every six weeks.

Did it work? The pupils certainly enjoyed the process and there was evidence of the vocabulary becoming embedded. But did they remember the words better?

In his most recent test, nine months after the baseline, 100 per cent of the dual-coding group pupils improved their retention marks by 30 per cent in the terms that they had managed to create the images for within lessons. However, on terms that they had not yet drawn images for, only 5 per cent improved in their score.

When testing the control group on the same terminology, the retention was not as strong - fewer pupils made as much progress.

So, great news, you might think. Except, there was a problem: drawing those images took time. And Adam found that the time spent making them was disproportionate to the gains made - there was not sufficient time in the curriculum to dedicate so much of it to this form of vocabulary instruction.

It required a rethink and a slight change of strategy for delivery. The concept had been proven to work but was there a way to avoid sacrificing so much time?

We had a discussion around his approach and Adam has moved towards setting dual-coding challenges as homework for his Year 7s - six words a week that will then feature in the next week’s lessons. Classroom time is not being overly burdened and the added benefit is a nice bit of sequenced planning.

Will it make the process more manageable? We shall see, but the initial results certainly suggest dual coding in this way is worth the effort if we can make it work logistically.

Henry Sauntson is assistant principal at City of Peterborough Academy

This article originally appeared in the 19 July 2019 issue under the headline “Read it, draw it, remember it”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters