‘We’re being told to cut jobs... but we need more teachers’

It is no secret that school finances are under enormous pressure. But where does the government expect the cuts to fall?

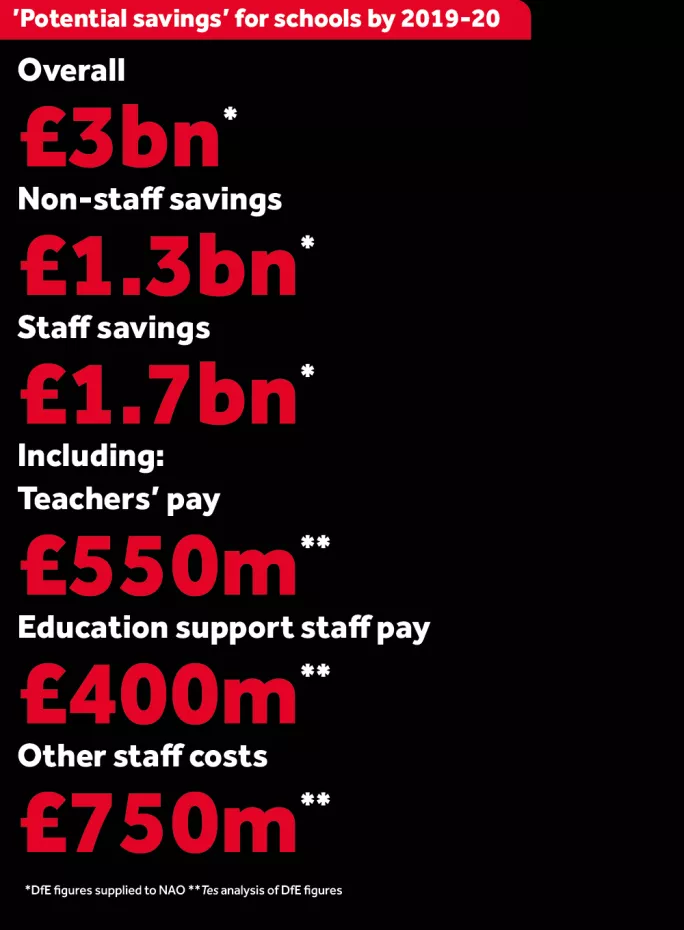

Schools may well be aware of the headline figure of £3 billion savings that the Department for Education says they must achieve by 2019-20 to meet government spending plans.

This figure is based on a £1. 7 billion cut to staffing budgets, together with £1.3 billion of procurement savings, and emerged in a National Audit Office report last December.

But the detailed thinking behind these figures, and what they could mean for job losses, had been unknown.

Cuts to staff pay

Now a Tes investigation has established the efficiencies that the DfE believes schools “could achieve” to produce the required savings, broken down by different areas of expenditure.

Previously unpublished DfE data, obtained through a freedom of information request, shows that the £3 billion figure is based on schools collectively cutting their budgets for teacher pay by more than £500 million.

That, experts say, is a lot of money for schools to save. But it is a disproportionately small 18 per cent of the overall expected savings when you consider that as much as 45 per cent of a typical school’s budget might go on teacher pay.

The DfE’s modelling is based on real figures - on what the most “efficient” schools can already manage.

So that relatively low percentage is a likely to be a reflection of how little fat there is left to trim from teacher wage bills. And some experts question whether even this level of extra cuts is possible without the quality of teaching suffering.

Peter Sellen, chief economist at the Education Policy Institute thinktank, says: “It is very uncertain whether such savings can be made without harming standards, and we don’t know whether cutting anything like £500 million from teaching budgets will be achievable.”

The DfE data sets out the savings that would be possible if the highest-spending schools brought their costs into line with comparable schools with similar pupil performance and pupil background.

It shows that schools would save £5.32 billion by 2019-20, including nearly £1 billion from the teaching budget, if no school spent more than the national median across 12 different areas of expenditure.

However, according to the DfE spending plans, only £3 billion needs to be saved by 2019-20. The DfE’s model suggests this would involve a £550 million cut to the teaching salary bill, equivalent to the average annual salary of around 16,000 classroom teachers.

‘Downplaying the impact’

Split over the four years to 2019-20, that would mean the loss of around 4,000 teachers - or an average of less than a fifth of a teacher for each of England’s 21,152 state-funded schools.

That perhaps helps to explain why the DfE believes its plan is achievable.

However, there are other cuts to consider. The model implies a £400 million cut from the education support staff bill, and a further £750 million saving from supply staff, premises staff, back office staff, catering staff, staff training and staff-related insurance. Then there is the £1.3 billion in non-staff savings such as premises, back office, energy and consultancy costs.

Russell Hobby, general secretary of the NAHT heads’ union, questions the scale of these “non-staff” savings. “I just don’t believe that these efficiencies are available in the non-staffing budget,” he says. “I think that the DfE is downplaying the impact it will have on staffing.”

The job losses already taking place in schools suggest that Mr Hobby may well be right.

According to a poll of 707 heads published this week, 1,161 teachers’ posts will have been lost by September across 14 counties as a result of the funding squeeze (see “Heads survey reveals ‘thousands’ of school jobs cut due to funding squeeze”, bit.ly/SchoolSqueeze).

But, in the context of spiralling workloads fuelled by changes to assessments and a growing curriculum, Andrew Morris, head of pay and pensions at the NUT teaching union, says: “We need more, not fewer teachers.”

He notes that some schools are having to close early to cope with the budget cuts, adding: “If you have fewer staff, you can’t deliver the same length of the teaching day.”

Morris doubts that schools will be able to make even £550 million of cuts to the bill for teachers without getting rid of more expensive older staff.

“The DfE is supposed to be supporting older teachers to work longer, not encouraging schools to get rid of them in order to employ cheaper, younger teachers to bring down the pay bill,” he says.

DfE modelling suggests that schools will find it easier to cut support staff than teachers.

Overall, support staff account for around 23 per cent of mainstream maintained schools’ staffing costs.

And our analysis suggests that they make up around a quarter of the staffing cuts outlined in the department’s findings on how £3 billion could be saved overall.

In contrast, teachers account for 61 per cent of school staffing costs - but make up only around a third of the staffing savings identified by the DfE.

Some heads have vowed to resign rather than make wide-scale redundancies. But for those who are determined to stay the course, are there ways in which they can wield the axe without harming learning standards?

More information needed

A widespread criticism being levelled at the DfE is that it hasn’t provided anything like the level of information required to help schools to make these difficult decisions.

The NAO’s report, Financial Sustainability of Schools, published last December, warned that the DfE had not been clear that it expects most of the “efficiencies” to come from workforce savings, and “cannot be assured that these savings will be achieved in practice” (see bit.ly/NAOsustain).

The following month, schools were given “benchmarking report cards” aimed at helping them to compare their levels of performance and spending with other schools.

But while this might show where a school is spending more than its peers on a particular area, it doesn’t suggest how costs could be brought down - or whether it would be appropriate to do so. A school could arguably have perfectly valid reasons for spending more than average on, say, teaching, even when compared against similar schools.

Luke Sibieta, associate director at the Institute of Fiscal Studies, points out that although the DfE’s data shows large variations in how similar schools spend their money, it doesn’t demonstrate that they could achieve the same outcomes with lower spending, or achieve better outcomes by changing how they spend their money.

“If schools are spending more in one area, they may be spending less in others,” he cautions. “This analysis cuts spending in one area without increasing elsewhere.”

For example, spending less on employing full-time teachers could lead to a higher reliance on supply teachers.

Morris agrees, saying: “A lot of the benchmarking data is useful, but I never found the staffing benchmarking data as useful. If you push a bit here, it bulges out over there.”

Data ‘used as a weapon’

Morris feels that the DfE is “increasingly keen on using benchmarking as a weapon, as opposed to [using it] for helping [schools]” and that staffing is a particularly complex and difficult area to achieve large savings in.

“Every school can probably get the same deal on their photocopying contracts,” he says. “But the teaching and support staff workforces are the biggest areas of spending - and a school can’t become the average school.”

A DfE spokesman says: “Our analysis, which was outlined in the NAO’s report, compared spending across schools facing similar levels of challenge and achieving similar levels of attainment, and showed there is significant scope for efficiency.

“It is important to be clear that the figures from the various scenarios are in no way targets for savings - this would be misunderstanding the analysis. They are a way of testing and illustrating the achievability of the £3 billion of total efficiency savings on per-pupil funding by 2019-20.

“We recognise that schools are facing cost pressures but we are confident that they are well-placed to respond. That is why we are also providing additional support to schools to help them use their funding in the most cost-effective ways, including improving the way they buy goods and services, while our recently published School Buying Strategy is designed to help schools save over £1 billion a year by 2019-20 on non-staff spend.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters