Why schools should teach pupils how to lie

Should we teach children to lie? At first glance, the answer seems very obvious: no. Apart from anything else, children don’t really need any encouragement to lie - they learn to do so from as young as 3 years old, when they first realise that other people are not mind readers.

“Lying begins [when] children understand that they can create a false belief in someone else’s mind,” according to Dr Hannah Cassidy, a senior lecturer in forensic psychology at the University of Brighton and an expert in deception.

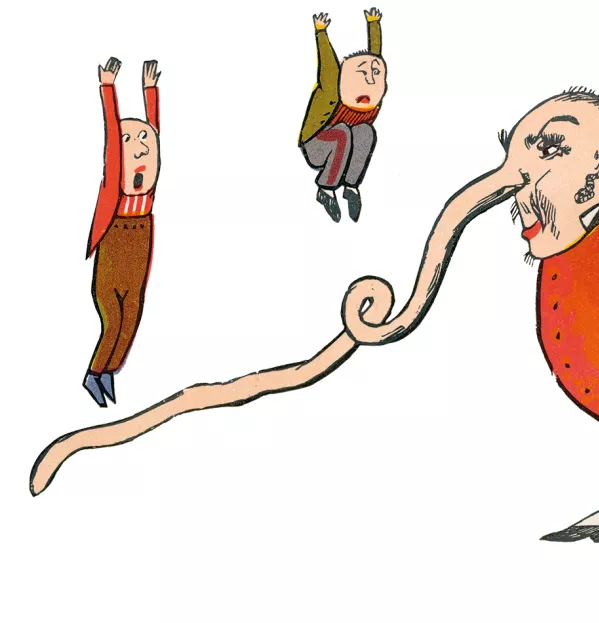

Children first try out comically inept lies, before they slowly - infuriatingly - become adept at lying with remarkable consistency.

“It’s natural,” you might think. “They need no help from us adults.” But, actually, there are two things you need to know about lying that might encourage you to reconsider.

First, learning to lie is a crucial part of a child’s cognitive development, says Angela Evans, associate professor of psychology at Brock University in Ontario, Canada.

“Lie-telling is a sign that children are gaining sophisticated cognitive skills,” she explains. “In order to tell a lie, children must prevent themselves from telling the truth (using self-control), hold the truth in memory (using working memory) and then create a plausible alternative story (using planning skills and perspective taking).”

Indeed, research conducted at the University of Sheffield and the University of North Florida, US, in 2015 found clear evidence that children with better verbal working memory were better liars, as they were better able to recall the details of the lies they had told to try to keep them consistent.

‘Social lubricant’

Assessing how good a child is at lying appears to be pretty useful, then. And this information may make you look again at students who frequently lie in your classroom.

But does this mean we should go so far as to teach children to lie? Instructing children in lying to boost those cognitive functions, rather than just assessing them, is a relatively unexplored field. However, it might be an interesting project for a school.

And schools might wish to take on that job even more when they hear the second reason for reconsidering teaching children how to lie: lies are useful for keeping relationships functioning. As Cassidy terms it, they act as a “social lubricant”. This is termed prosocial lying. We use it all the time - for example, when we protect people’s feelings by saying we like a gift from a friend, relative or partner, even though it is one of the most awful things we have ever seen. Ultimately, doing this demonstrates our ability to be empathetic and compassionate.

Children will gain understanding of the role of prosocial lying as they grow up, chiefly through observation. However, they do this at different rates and to different levels, which potentially leaves some with a deficit in the emotional skills required for later life, including at secondary school.

Tracy Alloway, a psychology professor at the University of North Florida - who was involved in the 2015 study mentioned above - explains that the ability to lie for prosocial benefits is not something we are inherently born with. It is a skill that must be nurtured, akin to learning a language.

“We have to learn the right thing to say when someone is sad or how to respond when someone is excited, and share that emotion,” she explains.

Is there a case to be made for actively teaching children this skill? You may, in fact, be doing it already - but you don’t call it teaching them to lie.

Emily Weston, a Year 6 teacher, believes this is often part of a school’s approach to educating its pupils to promote kindness and empathy, and making them socially aware.

“Truthfulness is one of our values and we have discussions in our classrooms about whether it is ever OK to lie,” she says. “At first, a lot of the children say ‘No’ because they think that’s what you want to hear. But as you start talking about it and raise scenarios, they start to realise there is more to it.”

Context and nuance

Weston says that it’s often about opening children’s minds to situations where a prosocial lie might be beneficial: “Sometimes they just haven’t had that life experience to see saying, for example, that you’re not hungry because you don’t like a meal you’re being offered is OK.”

Another example of a prosocial lie might be stopping someone from finding out about a surprise party: lying for this purpose is OK because eventually everyone will know the truth in a positive way.

Weston notes that, from a safeguarding perspective, this point about the truth eventually coming out is important for children to understand so they can differentiate it from keeping secrets.

Lucy Moss, a primary school teacher with 15 years’ experience, agrees that actively teaching prosocial lying is important, for everything from ensuring that older children keep the magic of Santa alive for younger pupils at Christmas to learning to show respect and tolerance.

“You see from around age 7 that [children] start to notice differences among themselves and the comments can become a bit naive. You have to make them realise you shouldn’t always just say what you think,” Moss says.

She admits that it can be hard to teach this, though: “Children can really struggle with the idea of lying as a positive, as it’s quite an abstract concept. So, we do have to have lots of discussions about why you should actually not be truthful all the time.”

Because it is tricky, the teaching of prosocial lying is not as overt as it could be (or happening enough, in some cases). Better advice on how to teach it would make a difference, giving teachers the confidence to embrace the topic, but unfortunately there is no definitive research on the most effective ways to teach children about prosocial lies.

In lieu of hard evidence, Alloway does have some advice. She agrees with Weston that concentrating on the motivation for this form of lying is crucial. “It’s about identifying the motivation as being prosocial and [then] encouraging [children] to think of situations in which they would apply or use that behaviour,” she says.

Evans adds that looking at potential outcomes can help, too. “Being more explicit about the consequences of both lie-telling and truth-telling in different situations may help children to understand the social norms of lie-telling,” she says. “For example, telling someone that you don’t like their drawing hurts their feelings, so you shouldn’t tell them that, even if you think it is bad. But if you have done something wrong or broken a rule, it is always important to tell the truth so that the problem can be fixed.”

Will this prevent a child getting the wrong message and telling their parents that the teacher told them to lie? Will it make you feel any less uncomfortable about the potential safeguarding dangers of teaching children to lie? The answer is no in both cases.

But the benefits of teaching children the right way to lie are clearly multiple, and with schools focusing more and more on social and emotional learning, we must find the best way of doing it - and not lie to ourselves about the need to do so.

Dan Worth is a content writer at Tes and tweets @DanWorth

This article originally appeared in the 17 January 2020 issue under the headline “Tell me lies, tell me sweet little lies”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters