Why teachers need to pause before falling for flipped learning

Of the new pedagogical approaches that have burst onto the British educational scene in recent years, “flipped learning” is among the most controversial.

It has been lauded by supporters as an approach that will revolutionise teaching, but dismissed by critics as a flash-in-the-pan fad.

Unfortunately for classroom teachers, there has been little empirical evidence to help them to judge who is right. That is, until now.

The Education Endowment Foundation has exclusively shared with Tes the findings of a new trial - the first time robust evidence has been collected in the UK about the impact of flipped learning in a school setting. The research raises questions about an increasingly popular intervention being used across the country and, some claim, proves that schools would be better off spending scant funds elsewhere.

As its name suggests, the idea of flipped learning is to turn traditional classroom education on its head.

The “teacher talk” part of the lesson is delivered at home using technology such as iPads and laptops, leaving the teacher free to use classroom time to help students apply concepts, rather than explaining them.

The EEF looked at “MathsFlip”, a flipped learning intervention that aims to improve the maths attainment of pupils in Years 5 and 6.

The programme was developed by Shireland Collegiate Academy, a secondary school in the West Midlands, one of the leading schools in the country in its use of technology.

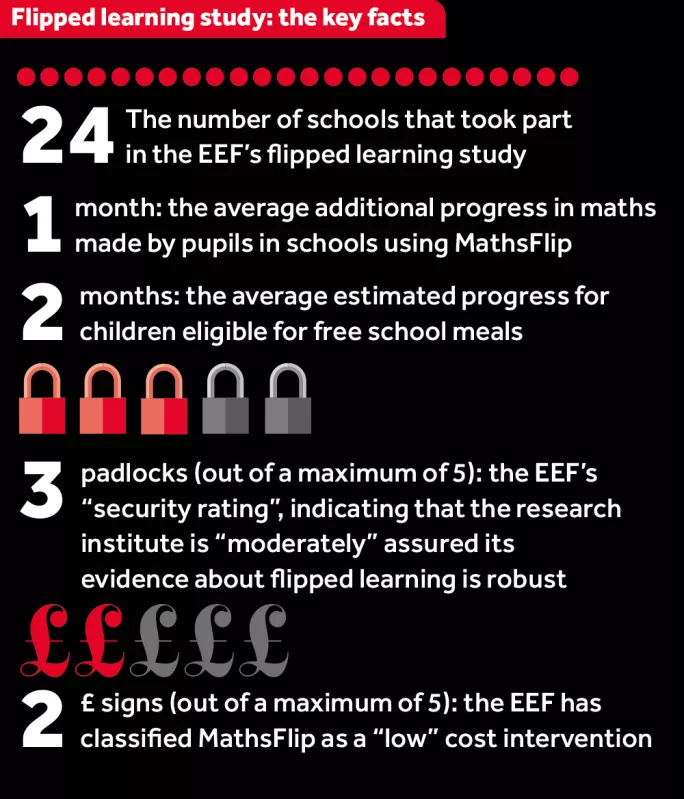

Twenty-four schools took part in the study, with 12 schools being supported by Shireland to adopt MathsFlip and the other 12 acting as “control schools”, carrying on their maths lessons as normal.

Pupils took home laptops and learned core maths content at home, before coming into school and participating in activities to reinforce their learning. They were tested before the intervention in Year 5 and again a year later in Year 6 with Sats.

So what did the research find?

The pupils taught using MathsFlip “made a small amount of additional progress” in key stage 2 maths, according to the EEF, “equivalent to about one month”. The impact on results for disadvantaged pupils was slightly higher.

While the flipped learning intervention applied only to maths, the EEF unexpectedly found that children in MathsFlip schools on average made three additional months’ progress in reading and writing.

However, it said that this result should be “treated with caution” because there was “not an obvious route” by which this larger improvement could be explained.

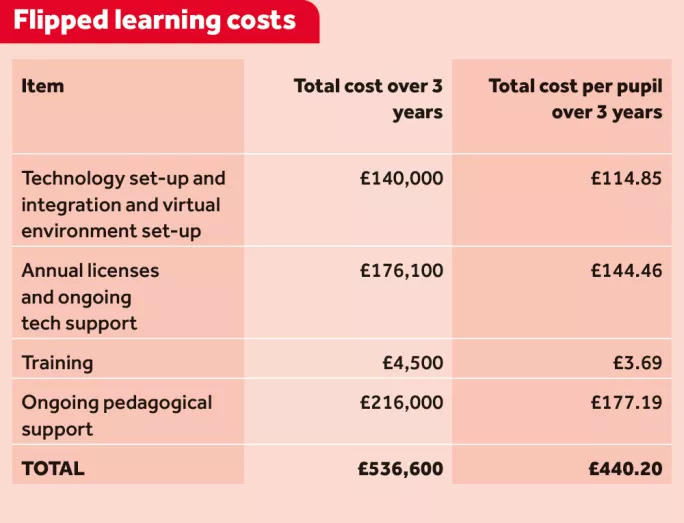

The gains linked to flipped learning should be weighed against its cost, which the EEF estimated at £147 per pupil per year.

However, that figure does not include expenditure related to hardware: the schools were supplied with 30 laptops each, at a cost of £5,667 per school.

Key features

Given that cost and the modest scale of improvement, critics of flipped learning argue the research confirms it does not offer value for money.

“Is this money, is this time, is this resource the best way to get this outcome? I would think the answer is certainly no,” says John Blake, head of education and social reform at the Policy Exchange thinktank.

Blake says that schools would be better off investing in “effective resources, training and particularly assessment processes” to support a “knowledge-rich” approach of teacher-led, classroom-based instruction.

“Some of the key features you would expect to see in high quality resources, are initial assessment - where are kids actually at - and then resourcing to help move them on, and then assessment to make sure they’ve done it,” he says.

But its supporters insist it is worth the cost. Kirsty Tonks, principal designate at Shireland Technology Primary School in the West Midlands and one of the project directors who rolled out the programme to the 12 test schools, believes the impact of flipped learning would have been more pronounced if the study, conducted between 2014 and 2015, had not coincided with a shake-up of the maths curriculum.

“The project, unfortunately for us, came at a time when there was huge change with the curriculum,” she says. “Teachers were distracted, because there was so much disruption.” She also points to “huge anecdotal and qualitative evidence” in favour of flipped learning.

The EEF certainly found that “the majority of teachers were very positive” about the intervention - some of those who were involved in the study now swear by it.

“I guarantee it’s more than one month’s progress with our children, we’ve had massive gains,” says Steve Payne, headteacher of Halesowen Church of England Primary School.

However, the EEF’s report flags up a number of potential barriers to the implementation of flipped learning approaches. Home internet access - and the implications this has for equity - can be a challenge.

And the approach’s success rests partly on the engagement of parents. With the task of “pre-learning” entrusted to students, those who do not apply themselves at home will see their education impaired. In fact, according to the EEF’s research, in one of the schools in the study that saw “limited” buy-in from parents, this resulted in between 10 and 15 per cent of students not doing tasks at home.

But Tonks argues that engagement is not a problem for the experienced flipped learning teacher, who can track the completion of online activities and step in where pupils are not doing the work. She also thinks elements of flipped learning - such as the use of online gaming to teach core content - are particularly appealing for “hard to engage”, predominantly male, pupils.

“They like technology,” she says “They prefer this way of doing their work at home. If you gave them a piece of paper, it probably would end up at the bottom of the street flying around, or the dog would have chewed it.”

For Blake, flipped learning strikes at a much more fundamental question about “what the teacher is for”. He thinks those teachers who promote flipped learning are selling their own instructional practice short. “[Flipped learning] is a very roundabout way of not doing very effectively something that we could do far more effectively just by teaching in the classroom,” he argues.

But while the EEF’s research might not provide a conclusive case for flipped learning as an efficient teaching approach, its expansion in the classroom alongside other “ed tech” interventions shows no sign of abating.

As Sir Kevan Collins, EEF chief executive points out: “The question has shifted from whether technology should have a place in the classroom, to understanding how it can be integrated into lessons to achieve specific learning goals.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters