And the moral of the story is...

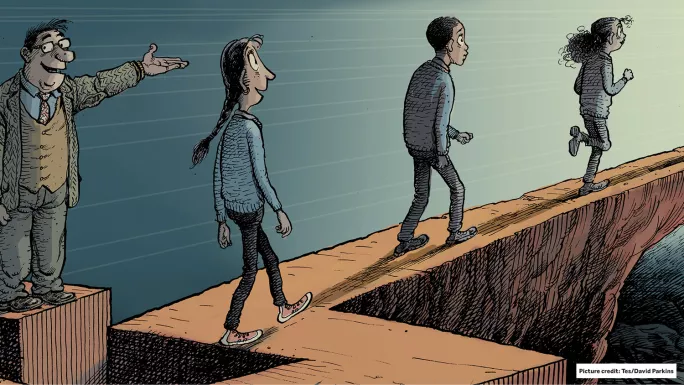

Is it the role of schools to develop moral attitudes and behaviour in their pupils? On the face of it, it seems sensible: schools, and teachers within schools, are society’s representatives in the development of our children. We trust them to produce the type of adults we need - not just in what they can do, but how they are.

Yet, implementation of that notion is not straightforward. Are there really universal moral values that schools can safely be relied upon to impart? Is it really a school’s job? In the past, it may have been uncontroversial that schools should be concerned with such matters, but to what extent do we now think that schools should be involved?

It’s a debate that is currently in progress in many countries around the world, and is highly relevant in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in particular. Because there, moral education is now on the curriculum.

For some context: the UAE is extraordinary, in that Emirati citizens are a small minority of its population of about 9.54 million - amounting to about 11.5 per cent. And although Islam is the official religion and Muslims probably make up the majority of the expatriate population, as well as the entire local population, a substantial minority are Christians, Hindus and others. Perhaps you can begin to see why the UAE government has introduced a “moral education programme”, to be implemented in all schools as a compulsory subject. It is intended to foster dogma-free and explicitly humanist values.

While the motivation underlying this initiative may primarily be to counter the negative influences to which all young people - especially those in the region - are subject to, it also aims to ensure that the diverse group of expatriates and citizens that make up the country have a better opportunity for integration, based around mutual understanding.

You may say that it’s not the job of education to impart a common culture, but it is something that Lord Robbins recognised as being an important aim of education in his report on the development of higher education in the UK some 55 years ago.

And in any case, a further motivating factor - and one that is common to the development of moral education elsewhere - may be a reaction against the perception of the increasingly utilitarian nature of school education.

‘The oneness of mankind’

The moral education curriculum emphasises the oneness of mankind, as a reaction against influences that emphasise “otherness”. And it is explicitly distinct from “religious studies”, which continues to be taught in a variety of flavours - Christian, Muslim and Hindu - depending on the composition of the school.

The programme builds on a growing movement around the world - moral education in Japan, for example, civic education in England, along with numerous other countries, and character education in Singapore - but arguably it goes further.

Among the reasons it has been able to do so is because of a political commitment to the programme among the country’s leadership (it actually began as an initiative by the Crown Prince), as well as the country’s tradition of deeply entrenched respect for authority, which itself arises from the fact that, as a federation, a strong centre has helped reconcile the interests of its disparate parts. Together, these factors have helped ensure acceptance of the approach and its implementation.

The initiative was launched as a pilot in grades 1-9 in September 2016 and was rolled out nationally a year later; it will be extended to all school years from September this year.

The development and implementation of the scheme has been largely UK-supported. The initial curriculum was developed by City and Guilds, the initial textbooks by Pearson and the implementation has been supported by an England-based education consultancy. The curriculum is based around four “pillars”:

* Character and morality.

* The individual and the community.

* Civic studies.

* Cultural studies.

Programmes of work and learning outcomes have been developed for each stage and each pillar, but, inevitably, in an infant programme such as this, these are being dynamically reviewed and refined in light of experience.

The fact that the pilot spawned a full-scale rollout tells you something about how this initiative has been viewed. By and large, pupils have welcomed and enjoyed the lessons (and even the homework to which they have given rise). Parents have generally been supportive, though there has been some questioning of the balance of responsibility between parents and the schools in fostering moral values. That trust I spoke of earlier can be hard won.

Some parents have also questioned the need for “moral education” instead of relying on religious studies. This is inevitable. However, the whole point of the programme is that it is positioned to stand alone and is concerned with global values, not connected to - or mixed up with - religious studies.

But perhaps the most nuanced reaction has come from the teachers: there has been particular concern about overcrowding of the curriculum and how a new, substantial programme is to be accommodated.

It’s a common problem across education systems: because society sees education as the core instrument of citizen development - above and beyond the role of the parent - every aspect of society wants a piece of the process. Quite simply, there is not enough time to fulfil every request. What eventually gets prominence is what makes it - officially - onto the curriculum. Moral education in the UAE is on the curriculum, and that forces teachers to look at what they can no longer do as a result. That will always cause challenges.

Other issues have been thrown up on the way to implementation - some predictable and some less so. First, there’s the preparation of textbooks and other teaching materials suitable for the different cultural backgrounds of the pupils who will be using them.

The ‘thorny issue’ of assessment

Then there’s the recruitment and training of teachers able to teach this novel subject; teacher training has been something that has consumed a substantial part of the effort and resources during the initial implementation, and the identification of teachers to teach the subject is something that will be resolved definitively only over time.

There’s also the thorny question of assessment: what is to be considered when assessing a pupil’s progress in moral education - is a child really to be assessed for improvements in their “morality”, or is assessment a purely paper-based and theoretical exercise?

Finally, there’s the balance between the responsibility of the home and school in teaching moral values.

One interesting, and slightly surprising, issue that has not yet arisen concerns the identification of the global values that are the subject of moral education. The key ones are:

* Fairness, affection and justice.

* Honesty.

* Tolerance and respect for differences.

* Justice and equality.

* Compassion and empathy.

Perhaps it is the very breadth of these values that makes them uncontroversial. It remains to be seen what problems if any are thrown up as they are taught in the classroom.

It’s too early to provide a definitive assessment of the success of the programme, but in process terms, it appears to be progressing as envisaged. However, its long-term success in meeting its aims will, of course, be judged only in due course.

The instruments for assessing the eventual success of the programme’s outcomes are being developed, and include plans for a longitudinal survey - over many years - of attitudes and values in the population as a whole.

And the debate as to whether it is something that should be done at all will likely never have a final answer - at least not an answer with which everyone will agree.

Bahram Bekhradnia is president of the Higher Education Policy Institute

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters