Are parents to blame for bad behaviour?

As hysteria mounts over knife crime, school exclusions and persistent bad behaviour, “I blame the parents” is once again a common refrain. But to what extent does parenting affect how a child behaves in school?

Considering the number of parenting courses on offer through schools, and through government services, the perception is clearly that the impact is significant. But, as always, it’s a bit more complex than that.

When you focus on extreme examples - for example, the effects of childhood abuse and neglect - the research is as troubling as you might expect. Adverse early experiences - at the hands of parents or others - have been associated with certain regions of the brain failing to form, function or grow properly. This can have serious emotional and cognitive consequences, including an increased risk of behavioural problems. The impact on schools is obvious, and their role in spotting and reporting abuse is key.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the impact of special educational needs and disability. Certain diagnosable conditions result in behaviours that have nothing to do with parenting.

But what of children with home lives and parents that fall outside of the extremes and for whom SEND is not a factor? How far is parenting responsible for a child’s undesirable behaviours in school in those conditions?

It’s an emotive topic, and not an easy one to sum up neatly.

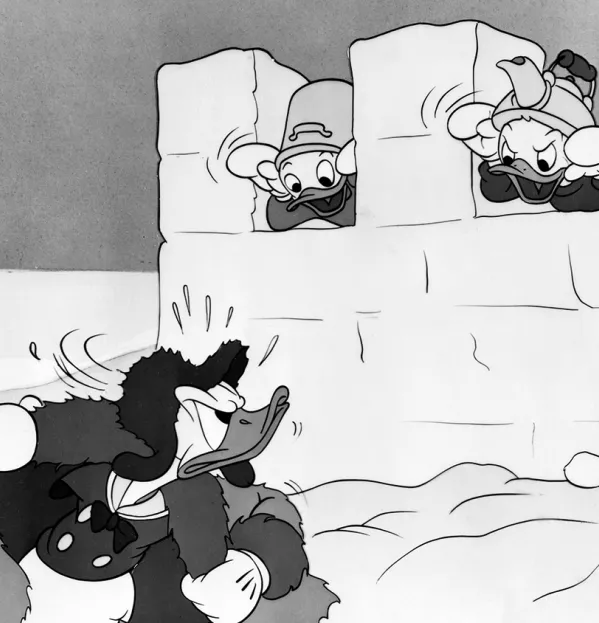

In the 1960s, the American psychologist Albert Bandura put forward his “social learning theory” : that people learn from one another, via observation, imitation and modelling. This was backed up by his contentious “Bobo doll” experiment, which showed that children who had watched an adult be aggressive to a doll were more likely to do the same than children in a control group who had not watched an adult attack the doll.

Parents who have sworn within earshot of their young children then heard them swear will be aware of this effect without the need for scientific evidence.

Social learning theory suggests parenting can be a factor in behaviour, and also offers hope to teachers trying to override possible negative parental influence because they can model the behaviour they want to see.

But a body of more recent research suggests that social conditioning from parents and other significant adults is far from the only thing shaping children’s behaviour and personalities. Studies of twins have shown that genetics has a stronger influence on the development of certain traits than was once believed and could even play a larger role than parenting.

The late psychology researcher Judith Rich Harris stressed the influence of genes in her popular but controversial 1998 book The Nurture Assumption, which also emphasised the huge impact of the child’s social groups in determining who they become. “The idea that we can make our children turn out any way we want is an illusion,” she wrote. “You can neither perfect them nor ruin them.”

More recently, Robert Plomin argued in his book Blueprint that genetics is a significant factor in all psychological traits, and that many environmental factors are genetically mediated. For him, there is little evidence that parenting has a bigger impact on who you are than your genes.

There is a fair bit of research bridging (and critiquing) the above two views and there is also evidence of other factors playing a role, such as socioeconomic situation. For example, a study at King’s College London found that, across most of the UK, 60 per cent of the variation in children’s behaviour at school was down to their genes. But in London, the child’s environment played a bigger part, something researchers speculated was down to higher levels of income inequality in the capital.

What about schools, though? Can teachers have a negative impact on behaviour, too?

One area in which research suggests that schools can have an impact on young people is through transmitting values, which then go on to form their underlying motivational and potential behavioural base in life. A child who has absorbed the value of achievement and self-advancement - a value promoted in the majority of schools - will be motivated to try to achieve, for example.

But Anat Bardi of Royal Holloway, University of London, recently carried out research on parents and children that revealed that simply valuing kindness could be the key to the transmission of all parental values.

“What we find is that parents who want their children to have values of kindness, those parents tend to be the most successful in transmitting all of their values to their children,” she says.

Bardi and colleagues from the universities of Westminster and Basel are now about to undertake longitudinal research in Switzerland and a one-off study in London to see if the same could be true for teachers in the classroom. Her team will look at how inclusive the classroom is, how the teacher relates to each student and whether children feel they can say things and ask questions.

“Based on the previous findings for parents, we are thinking that teachers who behave in a benevolent, kind way to the students will end up transmitting their whole system of values to the students,” says Bardi. “The idea is that when children are being treated this way, in a kind way, they become more open to absorbing the values of the person they have a relationship with.”

Research on schools in Israel has already shown the impact that principals can have on shaping children’s values. “Over the two years of our study, we found that children’s values grow in their correspondence with principals’ values,” the study concludes. “Principals’ personal outlook in life is reflected in the overall school atmosphere, which over time becomes reflected in schoolchildren’s personal outlook and ultimate behaviour.”

So, teachers can have an impact on values. And parents can have an impact on values. But in the domain of value transmission, genes passed on by parents (you guessed it) have also been shown to be key to which values people develop.

Ariel Knafo-Noam, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose work has looked closely at how values are passed on, says that teachers should take note of this in the classroom. “We can’t assume that everybody has the same motivations,” he says. “Any teacher will know that if you have 30 children in a class, you have 30 different individuals, even in a culturally homogenous context. They would come from different households with different values, they would have different personal tendencies for values.

“So when you say, ‘Don’t you want to succeed?’ and are pushing towards the value of achievement, this might appeal to some. Other kids might want you to say, ‘Don’t you want to understand?’ which would appeal to self-direction and autonomy values.”

As you can gather, the picture is complex. The evidence shows that children are the product of their parents through genes and parenting but also significantly the product of their environment and social context. This is still ongoing research: there are no absolutes. But based on what we know now, if a child is misbehaving, playing a blame game is likely to be unproductive - instead, teachers should try to build a team effort to turn things around. Which hopefully, most schools will be doing already.

Irena Barker is a freelance writer

This article originally appeared in the 28 February 2020 issue under the headline “Tes focus on... bad behaviour and blaming the parents”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters