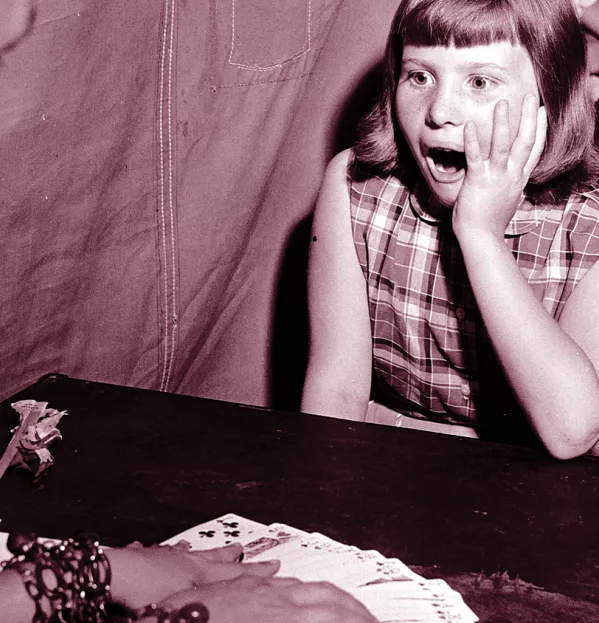

Avoiding the fortune teller error

When I taught in a secondary school, one of the most important days of the year was the one, very deep into the summer term (deliberately so, I suspect), when we found our timetable and class lists for the next academic year in our pigeonholes.

One such day sticks in my mind. I scanned the lists and a distinctive surname jumped out at me. It did so because it was shared by half a dozen siblings and cousins who all had behaviour and learning difficulties of some sort and were - to use language I resorted to when I inexcusably didn’t know any better - a nightmare.

The boy in question was joining Year 7 in September, so I’d never even met him, but I had already consigned him to my watch list: someone to impose my will on early, someone who needed to understand who was boss.

Two things happened in September: I learned that he wasn’t in any way related to that family, and that he was delightful and had a wicked sense of humour.

I felt incredibly guilty afterwards for writing him off and realised that, had he been a member of the family in question, he could easily have been just as delightful. It was a salutary lesson that has never left me. I had predicted failure based on one very dangerous and erroneous assumption. I had made the fortune teller error.

This prediction of failure is but one of a number of exaggerated or irrational ways of thinking that, I would suggest, we use regularly when we respond to or think about the behaviour of children.

In the 1970s, the American psychiatrist Dr Aaron Beck explored cognitive distortions (“faulty thinking” is another term for this) in his work on depression. I have found this to be a rich source to challenge my thinking on the behaviour of children when I make such mistakes. Here are some of the most common cognitive distortions that I see and make.

All or nothing

“Sîan, you have to be perfect for the rest of the term or you can’t go on the class trip.” All-or-nothing thinking places children in an almost unwinnable position by demanding perfection, or else they will fail. The faulty thinking is reinforced by the notion that we are extrinsically motivating the child to hold it together for the trip and, therefore, assume that prior negative behaviour was just a premeditated choice to be naughty.

To compound this, we tend not to impose such unattainable expectations on the rest of the class. This child has to work harder than their peers, despite their difficulties.

We feel helpless and frustrated when senior leaders or the Department for Education set us targets that we have no chance of meeting, so we need to recognise when we create similar situations for our students.

Ignoring positives and focusing on negatives

“Lara has had an awful week.” This maintains negative beliefs despite the fact that they may be contradicted by the actual evidence of a child’s conduct when viewed across the whole school. This can be reinforced in a secondary environment where we are almost certain to see only a partial picture of a child’s time in school, which we then extend to all other teachers and times of the day.

Labelling

My unforgivable description of an entire family as “a nightmare” is a case in point. Labelling - or mislabelling - uses very strong, emotionally loaded language in an extreme form of generalisation, extending one area of difficulty a child may have to their entire being or, in my case, their entire family.

Catastrophising

“Emily is going to destroy my lesson today.” This is a nuclear version of the fortune teller error. Not only is there a prediction of failure, but an assumption that things will go pear-shaped on an epic scale.

Fallacy of control

This is a form of self-emasculation whereby we see ourselves as helpless and at the mercy of fate. It weakens our position as we feel little or no ability to influence, change, and therefore improve, behaviour.

If we’re honest, we’ll all admit to having done one or all of the above at some point. I have. It is very hard to train ourselves out of these mistakes, especially when times are tough.

That is why it is so important to challenge each other when we encounter the use of such labels. It’s easier said than done, but it is vital if we are to develop a culture where such limiting thinking is never heard.

Jarlath O’Brien is headteacher at Carwarden House Community School in Surrey and the author of Don’t Send Him In Tomorrow

@JarlathOBrien

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters