‘Being black in education does matter’

I always resisted the idea that I could be of service to children just because I looked like them. As a black woman who grew up on Dartmoor, I had little in common with the children I taught in inner-city Bristol. It would have been presumptuous and inauthentic to assume an understanding of the context some of my pupils were growing up within, just because we had a similar skin colour.

Yet, there was always a quiet acknowledgement and an air of relief among certain pupils - the black pupils - when they knew it was me, rather than a non-black colleague, who would be intervening in a potentially difficult situation, such as a dispute with a teacher or peer.

I have come to realise that racism is present within the system

I have battled with this for a while: the sense of responsibility to those students but also the need to be free of the responsibility; the need to be defined, as a teacher, not by how I look but how I am.

My conclusion? I have increasingly had to face the fact that being black in education does matter. I have come to realise that racism is present within the system and this challenges my belief that as a black female school leader, anything is possible.

The fact that institutional racism exists is evidenced, in part, by a significant lack of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) people entering the teaching profession, and the reality that those who do enter are impeded from progressing along with their peers. This should be a scandal in schools. But it’s not, it seems. And that is something that should be of deep concern to all who work in the profession.

The brutality of racism

I come from a family of black educators. My parents met at teacher-training college, where both of them were training to be PE teachers. I have two aunts who taught and led in the US. One is an extremely successful senior administrator and the other is now retired. The women in my family are go-getters, they are creative, industrious and intelligent, and I was taught from an early age not to let anything stand in my way.

I attended a multicultural school in North London until the age of 10, when my parents moved us to the edge of Dartmoor, Devon. The relocation forced me to begin navigating a terrain that was going to become increasingly familiar. A terrain in which I was one of very few black faces.

In Year 7, on my first day of secondary school, I had my first encounter with the brutality of racism. A group of Year 10 or 11 boys marched past me in the playground barking in unison, “Pull that trigger, shoot that nigger.”

The words landed like a body blow and I remember wanting to never again be “caught out” like that. I learned to be hyper-vigilant. I learned to observe people around me with much more care so as to anticipate much earlier what the potential for acceptance or abuse might be and in order to modify my behaviour accordingly.

This behaviour modification took a number of forms. At school, I became the kind of pupil who “behaved well”. I was a super-fast runner and I liked sport, so I participated in everything from hockey to athletics. I wanted to be liked and developed my quick wit for laughs; I fought battles for the good of all and put myself forward as the class rep. I did my homework, helped teachers out. I never misbehaved. I carved several niches for myself at school, and, looking back, I can see how effective I was already becoming at the art of social navigation.

On hearing, as I sometimes did, “Yes, but you’re not black, you’re Angie,” I balked. But I was also thrilled. I was black, but my blackness was understood as non-threatening, a colour accident on someone who was, to all intents and purposes, the same as those I was surrounded by.

My first teaching post was at a big secondary school in central Bristol, and it was the first time, since leaving primary school, that I encountered a large number of other people from BAME backgrounds: 70 per cent of the student population was from a BAME group. But, as is the case across the country, I was one of only a handful of BAME teachers.

The school struggled to recruit teachers and so my appointment was not the biggest hurdle I have ever had to overcome. And the principal believed that the under-representation of BAME teachers on leadership teams of schools was a critical issue.

Unacceptable structural barriers do exist for BAME educators

When I spoke to him recently, he remarked on my appointment and promotions. The fact that I had the right skills, aptitudes and abilities was foremost in the decision to promote, he said, but had there been two candidates, myself and one non-BAME candidate with equal skills, then the diversity I would bring to the team would have been an advantage.

It is certainly because I worked under a principal so intent on smashing through glass ceilings, but also determined to provide positive role models to the children in the school, that I made a quick leap through the ranks. In a few years, I became a senior leader and did not experience direct discrimination or explicit racism at any point.

I then moved on from my job as a senior leader to become headteacher of the pupil referral service within a small rural local authority.

On taking up the post, I soon found that the pupil referral service was a fascinating counter-culture and actually consisted of a fairly empowered collection of children and adults who, rather than being excluded from the mainstream, had chosen to exclude themselves from the mainstream. They defined this space with a deep regard for each other, a respect borne of understanding that was quite unique.

I spent a couple of years there and then launched into my current role as the principal of one of the country’s few state-funded Steiner schools. Again, I have found myself operating in a space outside of the dominant education culture, and yet confounding expectations even there: one of the more common questions I am asked is about Steiner’s views on race…

Looking back, particularly at these last two posts, I can see that I have created many viable alternatives for success outside of mainstream spaces. I recognise that it has been necessary, at times, to successfully navigate the centre space and that this has meant the adoption of the correct codes, norms and values in my working life, as much as I ever did when I was a child. But for the most part, I have forced myself - or rather, I have been forced - to work on the margins.

But I now find myself compelled to give voice to some truths that may be more difficult to hear within the arena in which I have always “behaved” so well. Because, however I choose to articulate my thoughts on the matter, there is overwhelming evidence that unacceptable structural barriers do exist for BAME educators.

The workforce census of 2015 indicates that out of the 21,356 headteachers who provided ethnicity data, 20,715 (97 per cent) identified as being white, while just 277 (1.3 per cent) identified as being black. The total number of headteachers who identified as BAME was just 640 (3 per cent).

Those heads rose from a group that is itself under-represented. Just 2.5 per cent of classroom teachers identify as black and just 8 per cent as BAME. The 2011 census for England and Wales found that 14 per cent of the population identified as BAME. So although I (somewhat disingenuously) argue that I have not experienced “explicit racism”, my historic refusal to characterise unconscious and implicit bias as institutional racism, as well as the self-imposed “thwarting” of my career, plays into this structurally deficient model.

Admit to prejudice

So, what do we do about it?

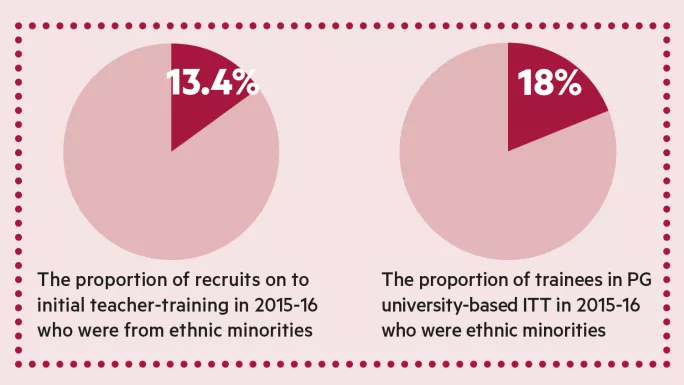

Some routes into teacher-training still struggle to recruit BAME candidates. My experience of teacher training would suggest that providers need to do more, not just to make courses accessible to applicants from diverse backgrounds, but also to be realistic about the challenges that BAME educators may face beyond the training itself.

It is an extraordinary reality that the face of institutional racism is left hidden in the shadows when it comes to teacher training, when so much of the content of these courses now reflects the need to reverse historic underachievement for BAME groups.

Nick Dennis, a teacher in North London who has written for TES on unconscious bias, points to the recruitment process as another opportunity to make a difference.

“We also have to consider that there is this bias in the system but it is not the upfront bias that characterised racism in the past. If this is not accepted as a general context for recruitment and something to be aware of, then it is quite hard to move forward in terms of recruitment,” he says.

Dennis goes on to say that we must make sure “that the people running the recruitment process are aware of any potential bias and this may start in the wording of the advert and job description. Recognising that there are underrepresented groups and that the school/chain wants to address this clearly in the advert (within the law) shows commitment.”

I worried that in speaking out about racism, I would somehow damage my professional reputation

And teachers, too, have to examine their own unconscious bias. All of us. Of every colour. We need to be open to it, examine it, attempt to correct it.

But it can be a two-way thing - we BAME educators need to force change, too.

I was recently invited to join #BameED, a grassroots movement founded to address the lack of BAME educators working at leadership level in schools. For a while, following the invitation, I couldn’t work out my disquiet. I felt motivated by a personal responsibility to help address the disparity in terms of the numbers of BAME people who make it to school leadership, but I also felt exceedingly uncomfortable acknowledging that racism has affected me personally. My desire to improve the situation for BAME educators who find themselves marginalised within the system was strong, but I have to own up to an anxiety, that in speaking out about racism, I would somehow damage my professional reputation.

Over the years, although I have complained to close colleagues, friends and family about being the only black person in the room - at school, during teacher training, at CPD events and so on - it has always been expressed as a rather vague dissatisfaction. It was left vague because an examination of the reasons why might end up with me drifting painfully close to the realities of institutional racism.

I have begrudgingly accepted this status quo, infrequently, and always privately, giving in to the exhaustion and the pain involved in fighting one’s way to the top of this sector.

It has been necessary for me to believe that I have agency in order to maximise my options. It has been absolutely necessary for me to believe that I am creating and shaping my future and my success, for without that hope, then madness or failure. It has represented a somewhat inconceivable position for me to accept discrimination or racism.

But now, for me at least, and possibly for other black educators, it is time to step out of the realms that feel familiar and really start considering where and how else we might be of use. There is nothing more inspiring to children than a teacher enthralled by their work, inspired by their mission, full of purpose. The idea that black educators can be of most use to those children who look like them, acting as role models for BAME young people, maintains a status quo of sorts. It supports false notions that because we come from a BAME group we must somehow “give back” to BAME communities. We need to push beyond this. The idea stops the education system at large from being able to meaningfully embrace diversity.

And so this is what I hope to do. To push on, out and into the centre ground. To talk about and get other people talking about, race in education.

In How it Feels to Be Coloured Me, Zora Neale Hurston talks of the surprise of discrimination: “Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can anyone deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

I almost want to go further than that and ask: “Who am I to deny others of the pleasure of my company and the stories of my journey?”

Angela Browne is headteacher at the Steiner Academy, Bristol

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters