The ‘blatant Canadian failure’ that still haunts

A teacher burns sage before fanning the smoke around her teenage pupils with a feather.

The ceremony is called smudging. Once it is completed, the 16- and 17-year-old teenagers make dreamcatchers - wooden hoops, covered with a woven web and used as protective charms against bad dreams - as loud indigenous people’s music blares out.

This is normal practice for pupils on a social studies course at Notre Dame Catholic High School in Ottawa - Canada’s capital. Like most schools in the city, only a small minority of pupils and staff are actually indigenous.

But everyone in the high school is exposed to the cultures of the country’s indigenous people through artwork, books, traditions and restorative conflict resolution.

Canada celebrated its 150th anniversary this month amid an increasing recognition of the people who populated the country thousands of years before European settlers arrived.

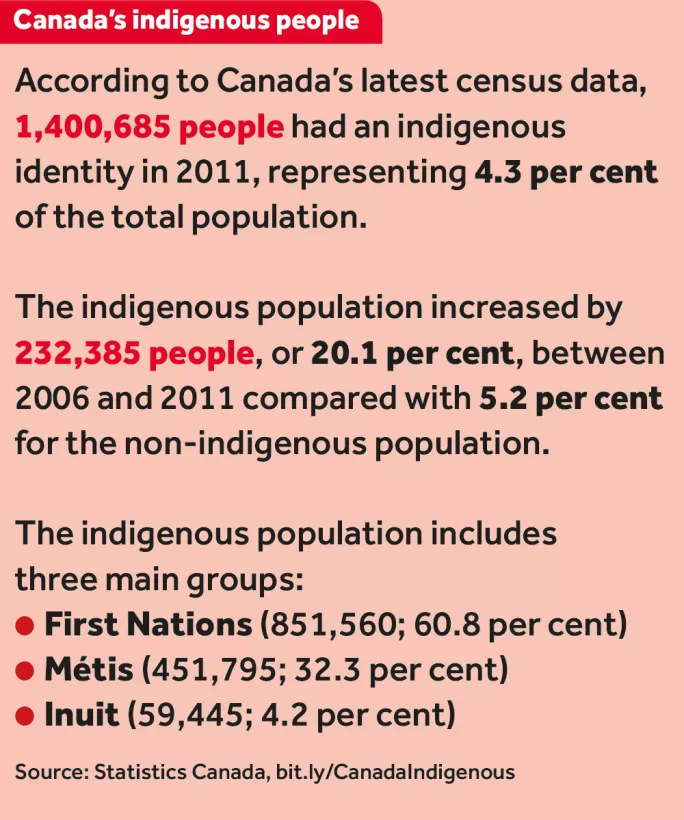

It hasn’t always been this way. The First Nations, Inuit and Métis people who make up about 4 per cent of the population may be the descendents of the original inhabitants, but until recently their traditions were widely ignored by the country’s schools.

And for more than a century, thousands of indigenous children were forced to attend state-funded, church-run residential schools - rife with sexual and physical abuse - far away from their families, in a deliberate attempt to suppress their ancestral roots.

At Notre Dame Catholic High, teacher Alanna Trines, who is First Nation, says that many pupils did not know what residential schools were when she first started her social studies course on indigenous people in 2001.

Today, sitting on a wooden bench in the school’s “restorative practices” room - a dedicated space decorated with colourful flags of indigenous peoples and a circular “grandfather teachings” rug - she says things have improved.

From September, the school will offer an English course in indigenous people’s literature alongside its social studies and arts courses.

Trines’ high school experience was very different in the 1990s. There was a silence about indigenous people; she only learned about residential schools through her independent research at university.

“I didn’t even know you could learn stuff about native people,” she says. “Nobody really talked about it. It wasn’t an important part of our [taught] history.”

The only acknowledgement of her roots came at the age of 9: “My teacher one day, during story time, said ‘Oh Alanna, get up and do a rain dance for us’, and I was like ‘What?’ I did not even know what she was talking about. Now when I look back, I think ‘Well, how inappropriate was that comment?’ I didn’t even know much about my own culture growing up because there was so much racism that my grandma denied that part of herself.

“She tried to pass as being Irish Catholic. She didn’t teach her kids anything because there was shame associated with that.”

Today, children can be introduced to the topic of indigenous people from as early as 4. In an elementary school in Ottawa, a kindergarten class sit on the carpet in silence as they watch their classmate Julian give a slideshow presentation about his First Nation background. He speaks about the significance of the grass dance before showing his classmates the dance moves, as older pupils drum a beat with wooden sticks on blue exercise balls.

And it is not long before the group of four- and five-year-olds at Our Lady of Peace School fill the classroom with noise, as they try out Inuit throat singing.

Julian is just one of a handful of children at the school who have identified as indigenous. About half of the First Nations people who make up the majority of indigenous Canadians live on reserves.

They attend schools run by the federal government, unlike the rest of the country, where education is run by provincial authorities.

Statistics show that those educated on reserves have the poorest outcomes. A report last year from research group CD Howe Institute found that only four-in-10 young adults living on reserves across Canada finish high school. That compares with seven-in-10 First Nations people educated off-reserve and nine-in-10 non-indigenous people.

Last year, prime minister Justin Trudeau pledged to improve the government’s relationship with indigenous people, committing $8.4 billion over five years. And the greatest portion of that money will go towards First Nations education: $2.6bn for primary and secondary schooling on the reserves.

Despite the olive branch, there’s still a long way to go to appease indigenous communities - especially those living on poverty-stricken reserves with high suicide rates. And the country’s 150th anniversary celebrations did not defuse the tension: just a few weeks ago, a group of activists set up a teepee on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in protest at the celebration.

John Malloy, director of education at Toronto District School Board, says: “It should be called the 150th anniversary of confederation. Our indigenous communities rightfully remind us that what we call Canada was here before 150 years ago.”

But it is clear from visits to schools in Ontario that the history of indigenous people is now firmly on the agenda. Every morning, all 584 schools across the Toronto District School Board - which serves the largest non-reserve indigenous community in Ontario - read out the names of the traditional territories on which they are located, over their PA system, before or after the national anthem.

There is a wider debate on the issue taking place across Canadian society; sports teams - professional, amateur and school-led - are under mounting pressure to stop using names, logos and mascots that may be deemed offensive to indigenous people. In 2014, the Nepean Redskins youth football team in Ottawa officially changed its name to the Nepean Eagles after an Ojibway musician filed a human rights complaint against the team.

Sitting on beanbags in an elementary school in the same city, Grade 6 pupils - aged 11 and 12 - discuss whether the Cleveland Indians, Washington Redskins and Chicago Blackhawks should similarly make changes.

Faye Hughes, who is teaching the class at St John the Apostle School - at which only a minority of pupils are indigenous - has made it her goal to challenge offensive terminology and stereotypes. She deliberately chose sport to stimulate a debate. “My class are big hockey fans,” she says. “I knew it would initiate some emotion and some good conversation.”

Her pupils have become passionate about indigenous people’s rights - but they haven’t always been like that. “When I first introduce it, a lot of children say ‘Are you talking about Indians?’ I get it every year. A lot of the children come to school with a really negative attitude about First Nation people. They think they are homeless alcoholics who get everything for free and don’t pay taxes.

“As we talk about them more and dig deeper into their culture, they develop their own passion for these Canadians who live here, too.”

Things are moving in the right direction, but not every school has cheerleaders like Hughes and Trines. And for some teachers, the subject is a daunting one - especially as the majority wouldn’t have been taught about the group when they were at school.

“For the last four years, it felt like a conversation I was having alone,” says Hughes. “There were not many people here who were interested or knew what I was talking about and it wasn’t something that was talked about. It should be school-wide, but it is baby steps.”

Another key challenge is getting indigenous families to self-identify, to ensure they benefit from targeted programmes.

Some indigenous pupils who attend schools off reserves in the public education system would not necessarily speak about their roots for fear of stigmatisation.

Taunya Paquette, director of indigenous education at Ontario’s ministry of education, says 63 per cent voluntarily self-identified this year. “This says to us that parents and families are feeling safe in Ontario schools,” she says. “They are feeling their identities are reflected.”

But educationalists say a number of families still hold back from identifying because of the past. “There was an assimilation process that occurred because we hadn’t acknowledged First Nations as we should have,” says Bill Hogarth, a former Ontario school board director. “I don’t think we realised the impact of residential schools and the embarrassment that caused.”

At Earl Beatty junior and senior school in a leafy suburb outside Toronto, far away from any reserves, headteacher Anastasia Poulis believes there is probably an indigenous pupil in every school in the country. “It’s about the conditions of the school that allow for that self-identity to occur,” she says.

World-renowned Canadian educationalist Michael Fullan is now working with the federal government on education provision for indigenous people and has found that one of the major issues on reserves is low teacher retention rates.

“The pay isn’t as good and you’re in a remote area,” he says. “They haven’t figured out policy incentives to make it work. So you get this revolving door of people going out for six months who then can’t stand it and come home.

“It is just a mess, really. Even as of today, it has been an out-and-out failure and therefore the responsibility is both at the federal level and the provincial level.

“It is a blatant Canadian failure, full stop. All of it has been a disaster.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters