Could yoga stop children doing a stretch in prison?

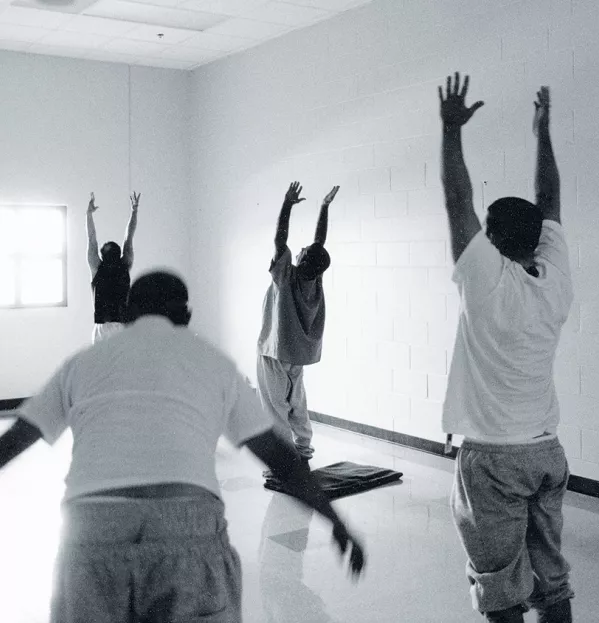

Yoga might seem an incongruous pastime for a tattooed biker doing a long stretch for murder. Its impact on hardened criminals, however, has persuaded a Scottish academic that this practice rooted in Eastern spirituality - and related to techniques such as mindfulness - could be critical in steering school pupils away from paths that lead to prison and wasted lives.

Ross Deuchar, a criminologist who has explored gang culture at home and around the world, believes yoga, spirituality and meditation have helped prison inmates move on from violent pasts linked to traumatic childhoods.

Professor Deuchar, assistant dean at the University of the West of Scotland’s School of Education, has studied gang culture in Denmark, Hong Kong and the US, and has just returned from a five-month Fulbright scholarship in Florida, where he spoke to some of the most violent American offenders.

He has also written a peer-reviewed chapter for an upcoming Danish book, Vejen ud Går Indad (The Outward Goes Inward), on violent criminals’ response to yoga.

“This approach really helps people to have a different kind of life and makes them more able to deal with anger,” he says, explaining that prisoners often have a fragile ego and a desperate need for a warped sense of respect and status - one inmate said that people like him were prepared to “kill if anybody’s threatening your image”.

‘Happiness and control’

The Danish prisoners - who will also feature in Gangs and Spirituality, an upcoming book by Professor Deuchar - went through two separate programmes, which have involved more than 250,000 prisoners and staff since they started in the US in 1992.

One programme involves an intense oneto-one introduction to yoga, breathing and meditation techniques over five days, followed by top-up sessions.

The Danish prisoners - all men - used Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY), which has been described as a “sequence of specific breathing techniques”. The impact matched that of previous clinical trials in which prisoners talked of being able to discard their “old selves”. Most had grown up in poor communities with limited job prospects, where violence was rife and gang culture dominated (see box, above right); alcoholism, abuse and parental loss or rejection were common at home. They said yoga gave them a sense of control, happiness and peace that was previously out of reach.

The Danish book quotes one inmate, Søren, as saying: “Something happens when you meditate - it’s like you’re coming home … you get in touch with some part of yourself which is maybe [from when you are] three, four, five years old and when you are [that age] you don’t harm anybody, so by practising every day you become a better person … you start to be more kind to people.”

Professor Deuchar believes that the impact of such techniques could be profound if used before violent and criminal behaviour become entrenched in young lives.

“Yoga or techniques such as meditation and mindfulness could make a difference to young people, in the home and in the classroom environment,” he says.

“You could see how it could help break that vicious circle, where children with a difficult home background then become frustrated at school, and lash out. Something like this could be really effective in terms of helping them become more ready to learn.”

However, in May, Tes reported academics’ concerns that lessons explicitly designed to make children happier, including seemingly innocuous interventions such as meditation or mindfulness exercises, could actually do damage. An over-emphasis on wellbeing in a school and the increasingly common use of techniques such as mindfulness, they argued, risked exacerbating problems and pathologising normal emotions, such as sadness.

Pooky Knightsmith, vice-chair of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition, said: “If a child is suffering abuse at home, being given space and time for thoughts to drift through your head isn’t necessarily good. Schools need to be aware of the potential risks, even with the most seemingly nicest of interventions.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters