The democratic deficit facing England’s schools

Of the many criticisms levelled at the academies system over the years, the lack of democratic accountability has been the most consistent charge.

In 2014, the Department for Education finally took note and introduced a new system of eight regional schools commissioners (RSCs) to make decisions closer to the ground, advised and challenged by boards largely made up of local school leaders. And, for the first time, there was democracy, with four academy leaders elected to join each headteacher board (HTB).

But now, with the second batch of elections underway this month, a Tes investigation has raised new questions about the legitimacy and effectiveness of the process. It has revealed that:

* More than two-thirds of state schools are not allowed to vote, even though they could all be directly affected by HTB decisions.

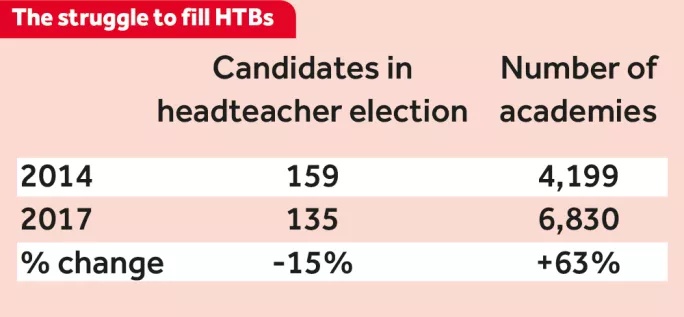

* Fewer academy leaders are standing in the elections, despite a big rise in the number of academies since 2014.

* Three-quarters of the school leaders elected in 2014 have decided not to stand again.

Disenfranchised schools

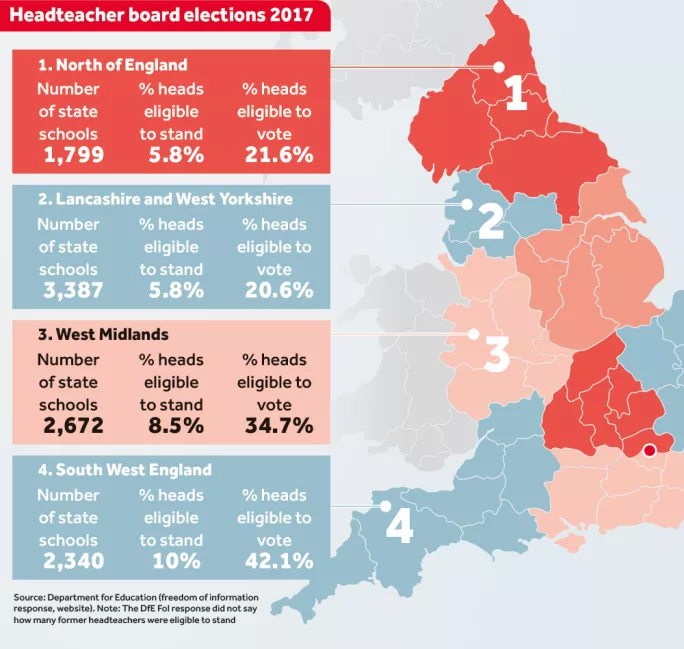

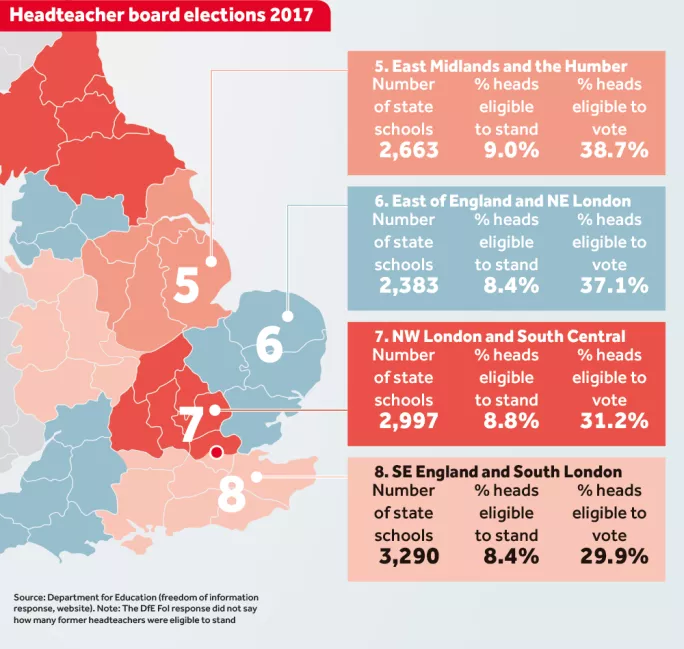

Only current or recent headteachers of academies judged outstanding overall, or good overall with outstanding leadership and management, are eligible to stand for HTB elections. And only academies are allowed to vote. This means that, out of more than 21,500 state-funded schools in England, less than 10 per cent of headteachers are allowed to stand, and that the two-thirds of state schools without academy status are completely disenfranchised. But today, RSCs and HTBs exercise considerable direct power and influence over maintained schools, as well as academies.

Last year’s Education and Adoption Act required maintained schools that are rated “inadequate” by Ofsted to convert to academy status. The process is overseen by RSCs and HTBs, which decide on the sponsor for the school.

They also determine the fate of maintained schools that fall into the government’s new “coasting” category - even if this does not result in academisation.

And the powers do not stop there. HTBs also recommend the approval or rejection of applications from maintained schools that want to convert or set up an academy trust. Their decisions about the approval of new free schools, or existing academies, also affect surrounding schools, whatever their status.

Emma Knights, chief executive of the National Governance Association, brands the “limited franchise” as “unfair”. But for her, the problem goes wider, and she questions whether the election process itself is able to produce the range of skills HTBs need to make the decisions asked of them.

“It comes back to whether voting is the best way - I think it’s fundamentally flawed,” she says. Knights contrasts elections with the direct appointments school governing bodies are able to make.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), believes the number of schools that cannot vote raises “a democratic discussion”, and may show that “something that was set up for a system as it was may not be entirely suitable for a system as it is”.

“When you listen to [national schools commissioner] David Carter, he increasingly talks about the whole system,” he adds.

“He has a very inclusive view, saying it does not matter whether a school is an academy, a free school or a maintained school: we want all schools to improve. The corollary of that would be that HTBs are also inclusive, otherwise it raises questions about why people in certain schools are making decisions about the rest of the population.”

The proportion of schools that are disenfranchised varies starkly between regions.

In Lancashire and West Yorkshire, almost 80 per cent of schools cannot vote in elections to the board that could help make decisions about them. In the South West, the figure is 58 per cent. No region has more than half of state-funded schools entitled to a vote.

The Tes analysis also raises questions about how much confidence academy leaders themselves have in the HTB system.

Despite a 63 per cent rise in the number of academies since the 2014 HTB election, and the fact that the system is much better known than three years ago, the number of people standing across England is down by 15 per cent (see above).

One current board member, who is not standing for election this year, believes the reputation of HTBs may be putting potential candidates off. “There are a lot of questions being asked about HTBs at the moment and there’s the transparency issue, and I think it’s making people nervous about being associated with it,” they say.

Barton says the fall in the number of HTB candidates has come despite a drive from the ASCL to encourage its members to stand. He adds that the situation is “not a triumph of the democratic mandate”.

For him, the decline raises questions about the time commitment involved in the role, as well as the reasons for the apparent disengagement in the sector.

Again, the picture varies from region to region. In the North of England, only six people put themselves forward for election - with four of them existing elected members. Had they not stood, the DfE would have faced the embarrassment of not having enough candidates to fill all of the positions.

By contrast, 25 candidates are up for election in South-West England.

Across England, three-quarters of those who were elected in 2014 have decided not to seek election again.

For one HTB member, who is not running, there are two factors affecting these decisions whether or not to stand: the time that the position demands of people who are already busy running a school or trust, and the extent to which the role is rewarding.

“Where I think there are issues to be resolved is that a lot of it is very procedural and very formulaic,” they say.

“We should know trusts better, so we can take more informed decisions.”

The DfE was approached for comment.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters