Don’t battle boredom - it’s the father of invention

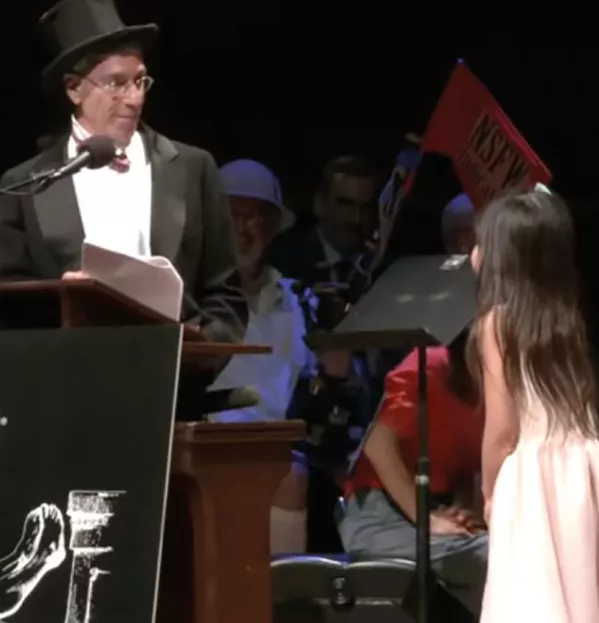

No one is immune. At the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony, the eight-year-old Miss Sweetie Poo tells the world’s most eminent scientists who drone on too long: “Please stop, I’m bored.” And she keeps repeating it until they do. And they do.

Those words have also been uttered by children to their exasperated parents down the generations. And, so I’m told, it just doesn’t cut it to tell them that they don’t know what boredom is unless they have experienced Sundays with only three TV channels and no shops open.

But, of course, we are all in a kind of time warp now: trapped in a repetitive rehash of the day before, with no prospect of a fresh perspective any time soon. As such, if there’s one thing that this period of social distancing and self-isolation has given children on an industrial scale, it’s boredom. There’s no playing with friends, no kickabouts, no extracurricular activities. Ballet classes, swimming lessons, piano tuition, drama club, all gone. Just like that.

All routines have gone out of the window. What’s taking their place? It’s boredom, of course, because there’s only so much Netflix anyone can watch and so many computer games anyone can play (after doing all the necessary schoolwork, of course).

And it’s not just children: it’s just as bad for adults. A study of the Covid-19 experience in Italy listed boredom as the second most common psychological complaint.

Boredom is a serious subject. There’s an entire annual conference on it - the Boring Conference, which was created in response to the cancellation of the 2010 Interesting Conference. Obviously.

And there’s even a whole lab devoted to it at York University in Canada. When our quest for neural stimulation fails, we get a feeling of boredom. It’s such an undesirable feeling, says the head of the Boredom Lab, Dr John Eastwood, that in laboratory settings some people actually resort to shocking themselves with electrical current.

In schools and in our homes, we try to stop children getting bored. We fear the reaction of a child faced with boredom. Bored pupils can be lesson wreckers. But although boredom may be an unpleasant feeling, it’s a normal one and it does serve a purpose. It tells us when we are at risk of stagnation, says Eastwood. So, despite making us feel uncomfortable, we are the better for it.

So, should we let children, and ourselves, be bored? One flag waver for boredom is Teresa Belton, a visiting fellow at the School of Education and Lifelong Learning at the University of East Anglia. It’s important for children to get bored and stay bored, she says, because it helps them to become independent and resilient.

All those after-school activities that parents lay on just teach children to rely on external stimuli provided by others for entertainment. They need to learn how to use their wherewithal to find their own entertainment.

“Qualities such as curiosity, perseverance, playfulness, interest and confidence allow them to explore, create and develop powers of inventiveness, observation and concentration,” Belton says.

Children - and adults - need to get bored and to allow their minds to wander, to daydream and to create. Necessity may be the mother of invention, but its father is, no doubt, boredom. This period may breed a huge litter of innovation.

And yet, like everything else, we should be cautious, too. For every yin, there is a yang; for every day, there is night; for every Obama, there is a Trump. And if, for any reason, this lockdown starts to break down, beware of people saying: “I’m bored.” Because it won’t be wilful rule breaking or disobedience that gets us into trouble, it will be boredom.

@AnnMroz

This article originally appeared in the 17 April 2020 issue under the headline “In times of tedium, remember that boredom is the father of invention”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters