Education could be a world of pure innovation

In March 2013, Ben Goldacre released a paper detailing a strong case for transforming the use of evidence in education.

“Building Evidence into Education” (see bit.ly/BEEGoldacre) called on the teaching profession to embrace evidence on an unprecedented scale and establish new ways of working that would help educators become not only the end-users of evidence, but also the generators and custodians of it.

Goldacre wanted research trials in schools to become mainstream. He wrote about a culture of active participation in research being fundamental to the practice and improvement of medicine as a profession, with most doctors playing at least a small role in larger and coordinated research projects as part of their professional life.

Fast-forward to 2017 and much has changed. More than half of all English school leaders now report using resources such as the Teaching and Learning Toolkit, to inform their spending decisions. More than a third of all schools have taken part in a randomised controlled trial - the “gold standard” of experimental research - to test the impact of different programmes and approaches.

In a “post-truth” world, the teaching profession’s claim to the custodianship of evidence about learning is more important than ever. It can help protect what happens in classrooms against the buffeting external forces of populism and it can guard against the internal forces of faddism to which teaching, like any profession, can be prone.

Goldacre’s paper drew on examples from his own profession to strengthen the case for a culture of evidence, tracing the hard-won steps of pioneers such as Archie Cochrane along the path to evidence-based medicine. On the face of it, it might be appealing to argue that education is different to medicine and that common sense and personal experience are enough to drive improvements in education policy and practice. After all, haven’t we all been to school?

But in the case of schooling, there are two key challenges to common sense. The first is that getting better outcomes for pupils is not only about doing what works, it’s about doing what works best. Public investment in education and the long term costs of poor educational outcomes mean that society cannot afford for schools to risk time, effort and money on anything less than the most effective approaches at the most cost-effective price.

The policy vacuum

Our second challenge is less straightforward. It’s the somewhat uncomfortable argument that a good share of the evidence about what works best in education is counterintuitive.

Consider ability-based grouping. Recent data (bit.ly/WideningGaps) has shown that the spread of attainment in the average classroom can span 5 to 6 years - that is, the average Year 6 classroom will likely include pupils working at a Year 3 level and some working at a Year 9 level.

It’s easy to conclude from this that it must be near-impossible for the teacher of such a class to effectively target the learning needs of each pupil and so grouping pupils according to ability must be a sensible and more effective way of organising the school. But the evidence (bit.ly/GroupingAttainment) indicates that while ability grouping might show small benefits for high-attaining pupils, it tends to be detrimental to the growth of mid-range and lower-achieving pupils, making the overall effect negative (see bit.ly/StreamingReferences).

This highlights one of the biggest challenges in education policy-making: in the absence of evidence, a vacuum is created that can too easily be filled by policy wonks with ideas that, while intuitive and no doubt well-intentioned, have little basis in evidence and can run counter to the cause of advancing children’s learning and development.

This is not an argument against new ideas in education or against applying new thinking from other fields. But it is an argument for testing those ideas first.

Let’s ask if and how they might transfer to the classroom and let’s engage with the evidence seriously, understanding that unless a new idea will help teachers to improve the quality of their relationships and interactions with pupils in a manner that supports deeper understanding, it is unlikely to lead to better learning.

The pioneering work of academics such as Carole Torgersen, Steve Higgins, John Hattie, Bob Slavin and Carol Campbell - and of many thousands of classroom teachers and headteachers - means a professional transformation that blends the art of teaching with the science of learning is now gathering pace.

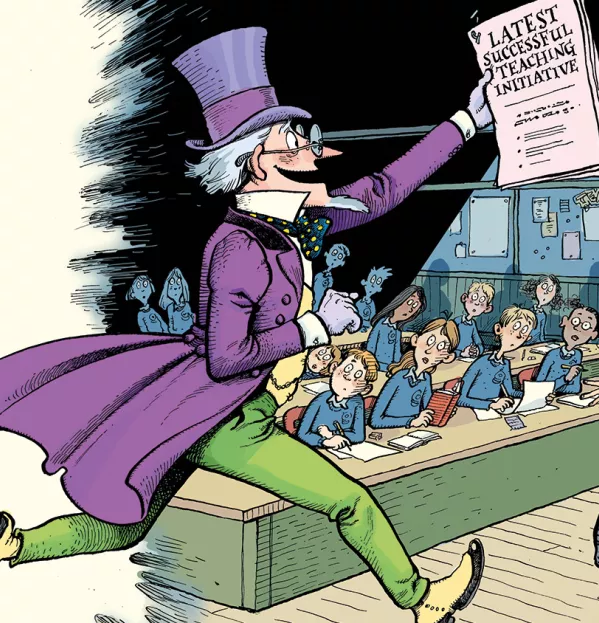

Time for a research ‘Wonkavator’?

The next, and arguably most challenging frontier, is about scaling: getting the most effective practices and the best available evidence to travel not just up and down from ministries to schools, but sideways between schools and back-and-forth in a cycle of feedback and challenge, continually building and refining the evidence and learning how to learn better.

With apologies to Roald Dahl and Gene Wilder, perhaps the education policy wonks need a Wonkavator: “An elevator can only go up and down, but the Wonkavator can go sideways, and slantways, and longways, and backways and squareways, and frontways, and any other ways that you can think of.”

It’s a challenge shared by education systems the world over. The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) is now partnering with teachers and school systems in Chile, Australia and across the UK to move beyond educational tourism and help grow good practice from within the profession.

The EEF’s Teaching and Learning Toolkit has been translated into Spanish and Portuguese and launched earlier this year in Latin America (bit.ly/LatAmEFF). This work is part of a global effort to scale-up evidence from the national to the international, moving to cross-border trials that help us to answer critical questions about the circumstances in which the evidence is applicable; about what is fundamental to the way humans learn and what is subject to the idiosyncrasies of language, culture and context.

It’s a far greater challenge. Not surprisingly, it is also one that the teaching profession has shown itself to be more than up for.

Stephen Fraser is director of international partnerships at the Education Endowment Foundation

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters