‘Empower’ teachers and close the attainment gap

Teachers, pupils and parents must have much more influence in schools if Scotland is to close its stubborn attainment gap, according to education policy experts.

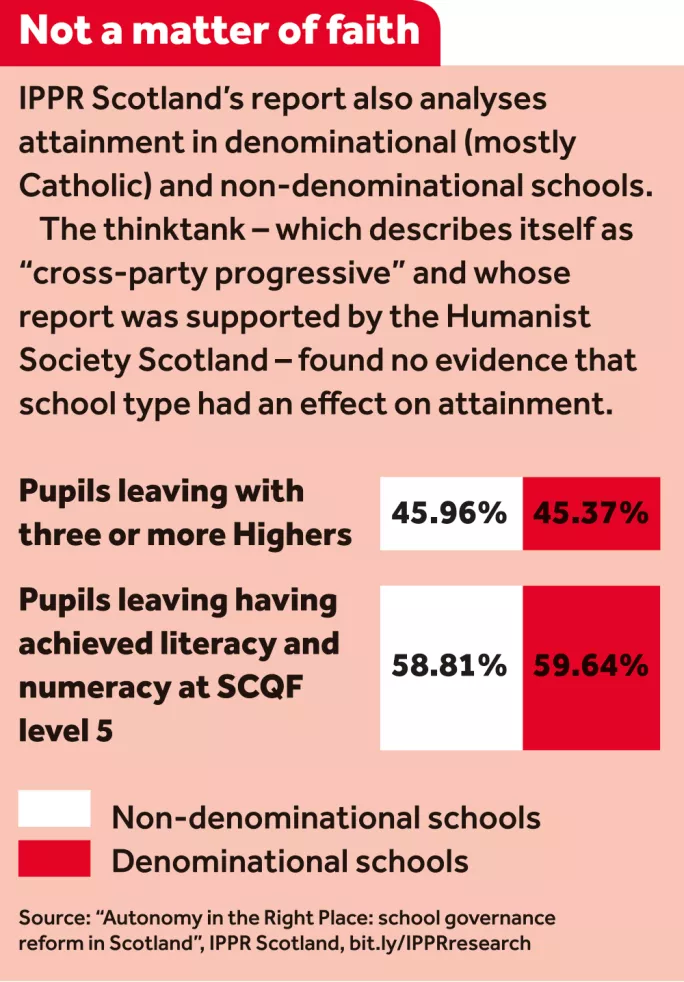

Education secretary John Swinney has stated his determination to hand more freedom to heads - but this does not go far enough, says a report by thinktank IPPR Scotland.

Autonomy in the Right Place: school governance reform in Scotland says it is more important to give teachers a greater say, even if that means they criticise school leaders and their local authority employers.

The report, which analyses a wide range of existing data and research from Scotland and beyond, concludes that “decisions, as a default, are best devolved to school level to allow locally informed decisions to be made in the best interests of all pupils”.

But to fully address the attainment gap between rich and poor - a flagship aim of the Scottish government, and a personal goal for Mr Swinney - “it is crucial that devolution does not stop at the level of school head”.

The report adds: “The evidence suggests that it is the classroom that will have the greatest impact on the attainment gap and, therefore, teachers should play a central role…to make use of their situated expertise.”

That includes giving teachers “a direct route to offer constructive engagement, feedback and criticism to decisions”.

In other words, “it is important that teachers are empowered…to contribute to, engage with and challenge decisions made at the school, local authority, regional or national level”. This should be at “the heart of any school governance changes in Scotland”, IPPR Scotland adds.

In June, Mr Swinney is set to announce the government’s response to the Education Governance Review launched last year, and he has already signalled that “regional boards” will be created to encourage staff to work across school and local authority boundaries.

IPPR Scotland, similarly, promotes the idea of “regional education partnerships” (REPs) and says that, as well as them having local authority members, places should be reserved for teachers, parents and pupils.

Parents ‘have big impact’

The report also stresses the importance of listening to parents and to pupils.

Previous research shows parental involvement has “a significant impact on the attainment gap”, write report authors Russell Gunson - IPPR Scotland’s director - and Jessica Shields.

But the report calls for new and more influential parent and pupil councils, which “should be placed at the heart of decisions in relation to the funding and design of activity to close the attainment gap”.

Last month, Tes Scotland reported on research in which pupils reported that their influence on school life was limited, with, for example, only about one in 20 feeling that they had a say in teacher recruitment.

Greg Dempster, general secretary of primary school leaders’ body AHDS, said teachers’ input would be “crucial” in areas such as the allocation of Pupil Equity Funding, a new £120 million government fund to help close the attainment gap by addressing local issues.

Similarly, Jim Thewliss, general secretary of School Leaders Scotland, which represents secondary heads, said that giving teachers more influence than in the past over decisions made in schools was a “commonsense” move.

Eileen Prior, executive director of the Scottish Parent Teacher Council, said that “a strategic, planned programme of parental engagement” should be “part of everything schools do to improve outcomes for young people”, and that improvements in this area were essential “to really address the attainment gap”.

Joanna Murphy, chair of the National Parent Forum of Scotland, said the involvement of parents in school activities was “hit or miss”, and often depended on the willingness of a “gatekeeper” to allow parents in.

She added that parents were extremely keen to help their children’s learning but often did not know where to start, and would need help from schools. This applied just as much in secondary schools, Ms Murphy said, where there was often a mistaken assumption that parents were less inclined to get involved.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters