Equal work but unequal pay for female leaders

The ongoing national controversy over the gender gap exploded again last month.

BBC figures revealing that more than two-thirds of the stars it paid £150,000 or more were male added more righteous indignation to one of the country’s longest-running inequities.

But education has no room for complacency. In less than a year, academy chains and large schools - state and independent - will have to reveal their own statistics on gender and pay.

And new Tes analysis of figures collected by the Department for Education suggests it too will not be pretty.

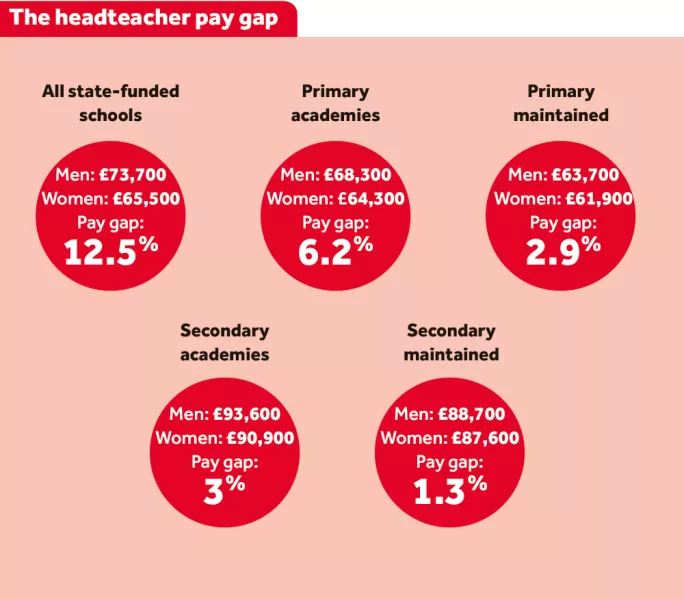

It shows that across all state-funded schools, male heads earn 12.5 per cent more than their female counterparts, with the average male headteacher taking home £73,700 per year compared to the £65,500 received by female heads.

Much of that pay gap can be explained by the overrepresentation of men in leadership positions in the higher-paying secondary sector. But not all of it.

Male heads still earn more on average than their female peers in every sector of the state-funded school system - in academies, at local authority maintained schools and across both phases.

This comes as no surprise to Mary Bousted, general secretary of the ATL teaching union.

“Women have never achieved equal pay for equal work,” she says.

“In that respect, teaching is no different from virtually any other profession. The only difference is that teaching is an overwhelmingly female profession.”

The DfE’s latest school workforce statistics for 2016 reveal that the biggest gender pay gap in any one sector is among heads of primary academies, where men earned an average of £4,000 - or 6.2 per cent - more than their female counterparts.

They took home £68,300 on average, compared to the £64,300 earned by the women who make up 69 per cent of primary academy heads.

In the highest paid sector - secondary academies - there is a 3 per cent gap, with male heads on average earning £93,600 a year, compared to the £90,900 earned by women.

The gender gap is also replicated at the very top end of headteacher pay. Of the 700 headteachers in secondary academies who took home more than £100,000 in 2016, 500 were men and 200 were women.

Men’s 71 per cent share of those who enjoy the top pay bracket cannot be explained away by their over-representation in secondary academy leadership, either - men have 64 per cent of such headships.

‘Disturbing, yet unsurprising’

A gender pay gap also shows up when pay for all teachers below headship level is compared.

In December, Tes revealed Office for National Statistics data showing that female teachers working in UK secondary schools earned an average of 6.4 per cent less than their male colleagues per hour.

However, in primary and nursery education, female teachers were paid on average 0.5 per cent more per hour than men, according to the ONS figures.

Chris Keates, general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union, described the findings on school leadership pay as “disturbing, yet sadly unsurprising”.

Both she and Bousted say that the gap is not just down to underlying gender inequality manifesting itself in education. They point the finger at recent government reforms, which they believe have exacerbated the situation - namely, schools being given greater control over teacher pay.

Academies have the freedom to create their own pay structures and automatic pay progression has been abolished in maintained schools.

Keates argues the greater the local discretion over pay, “the greater the opportunity for discrimination”.

“The door was opened wide to pay inequality when excessive freedoms and flexibilities were given to schools and the government embarked on its obsessive pursuit of deregulation,” she says.

“One of the things payscales do, and a clearly understood and defined national pay framework does, is act as a guard,” says Bousted.

“They act as a barrier to pay inequality. When you demolish that without putting anything in its place and leave it up to the market to decide, the market will decide in ways that are always highly unequal for women.”

It is true that the headteacher pay gap is lower in maintained schools, which are still required to follow the school teachers’ pay and conditions document and pitch salaries within an overall payscale.

While the gender pay gap is 6.4 per cent in primary academies and 3 per cent in secondary academies, it is 2.9 per cent in primary maintained schools and only 1.3 per cent in secondary maintained schools.

The disparity between the salaries of male and female headteachers is not the only gender pay gap affecting academy trusts. The problem also stretches to executive pay.

Tes analysis of official DfE statistics shows that in 2014-15 (the latest figures available), of 107 academy trustees earning more than £150,000 where the individual’s gender was identified, 80 were male and only 27 female.

What’s more, eight of the 10 highest-paid trustees in the country were men.

Keates says the “astronomical” salaries being earned by mainly male multi-academy trust CEOs disadvantages female leaders and “plays a leading role in depriving fair pay awards to the wider general, majority women, teaching population”.

While structural factors such as pay liberalisation and academisation might have contributed to the gender pay gap among school leaders, others think that there may be subtler forces at work.

Sian Carr, president of the Association of School and College Leaders, suggests that “women can sometimes be more reticent than their male counterparts about asking for more money, and this may be the reason behind the gender pay gap”.

She says it shouldn’t be up to individuals to negotiate equal pay - the responsibility lies with governing bodies to make sure pay and conditions are “fair and equal”.

“Likewise, governing bodies need to be ensuring they are helping people - both men and women - to step up to senior posts while juggling family responsibilities through the use of flexible working,” she adds.

A DfE spokeswoman says that the UK gender pay gap is at “a record low”, but there is “more to be done to make sure all women are treated equally”.

The government has required all large employers to record details of their gender pay and bonus data in April 2017 and publish it within a year.

The spokeswoman adds: “While it is up to schools to decide how much they pay their staff, the department is clear that governing bodies should pay full consideration to relevant equalities legislation when setting headteacher pay.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters