As exclusion rates rocket, the human cost mounts

The number of permanent exclusions in some areas rose by as much as 300 per cent in a year, a Tes investigation revealed last week, placing the subject back on the national agenda. But behind every exclusion statistic are real-life pupils. And what happens to those pupils once they have been asked to leave a school?

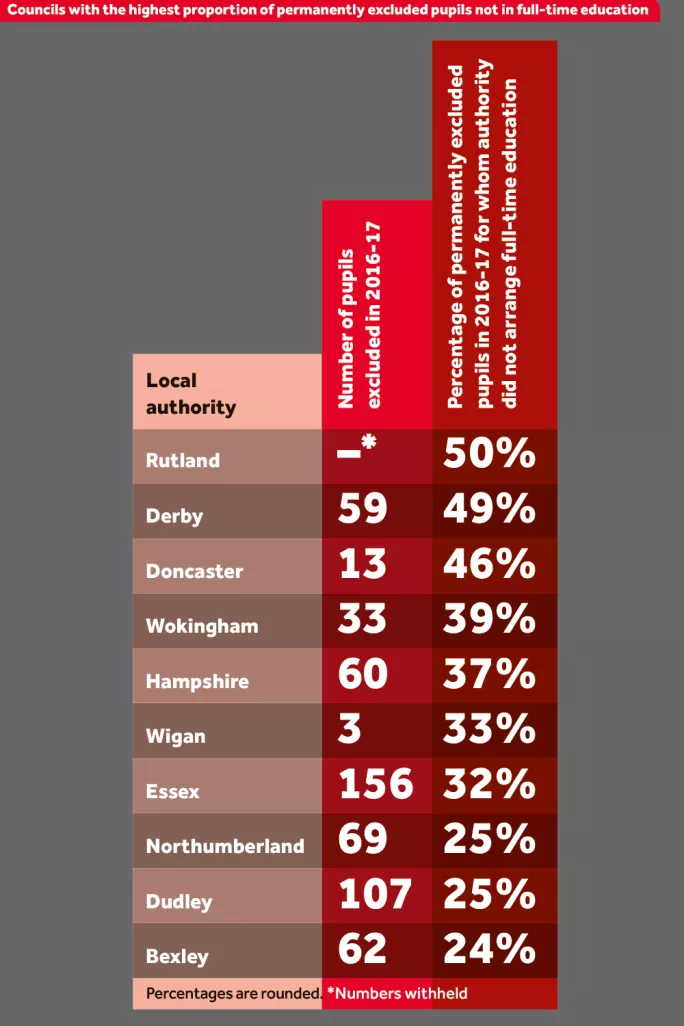

New figures obtained by Tes show that there are local authorities in which large proportions of the permanently excluded are not being provided with the full-time education they are legally entitled to. Three authorities are only providing about half of their permanently excluded pupils with a full-time education. A total of nine authorities have failed to fulfil their legal duty for at least a quarter of these pupils. Shrinking budgets are being blamed.

“Local authorities are expected to carry on and provide all the packages that are in place while their funding has been reduced,” says Colin Harris, a retired primary headteacher who has worked as a consultant at a pupil-referral unit (PRU).

Secondary schools receive an average of £4,800 annually per pupil, he says, whereas a place in a PRU can cost double this amount. “It’s expensive,” says Harris. “And local authorities don’t have the resources.”

Stretched services

Behaviour expert Jarlath O’Brien says pupil-referral units “are bursting at the seams”, leaving some pupils with little hope of getting a full-time place. He gives the example of pupils two terms away from the end of Year 11. “Those kids’ chances of finding another school are pretty much nil,” he says. “And it’s hard for local authorities to provide tuition for 25 hours a week. They can do something, but not 25 hours a week.”

Department for Education guidance states that the local authority in which a permanently excluded pupil lives has a duty to provide full-time education from the sixth day of exclusion. However, 29 of the 118 local authorities that responded to Tes’ freedom of information request are not providing that for all such pupils who live within their jurisdiction. Some are even uncertain of the destinations of their excluded pupils.

In Hampshire, only 36 - or 63 per cent - of the 60 pupils who were permanently excluded between September 2016 and 30 June 2017 received full-time education. Three of the remaining 24 pupils are not Hampshire residents, so their education is the responsibility of their home borough. But the other 21 are being given only part-time education.

In Essex, only 68 per cent of the 156 pupils permanently excluded in 2016-17 are currently receiving full-time education.

‘Reduced timetable’

A spokesperson for Essex council says: “They are receiving education commissioned by the local authority. In some cases, this may consist of a reduced timetable, which increases gradually and is reviewed regularly. Others will return to school and similarly may build up their timetable over time.

“A small number of pupils receive oneto-one tuition, pending reintegration into a pupil-referral unit.”

In Wigan, meanwhile, the parent of one of the excluded pupils declined an offer of full-time education, opting to school the child at home instead.

Harris points out that, when an excluded child is home-educated, the authority is statutorily obliged to visit the home and look at what education is being offered. “But I know that very seldom happens, because of the resources available,” he says.

And Loic Menzies, director of the education and youth thinktank LKMco, says that offering pupils home learning or a reduced timetable is not always in their best interests.

“We’ve seen examples of kids who have been excluded from school because something’s gone wrong in their lives, and then have ended up having a few hours’ teaching in a library here and there,” he says.

“Then that falls off, and what should be a temporary arrangement turns into a falling off of education altogether.”

But Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says that unconventional forms of education can work well for excluded pupils. “The most important thing is that they’re getting quality education,” he says. “I’m concerned with the quality of it rather than the quantity.”

Some authorities, meanwhile, are not even certain how many of their permanently excluded pupils are in full-time education. Nottinghamshire council originally reported that only 31 per cent of these pupils were in full-time education. However, when Tes followed this up, the authority said that the figure was, in fact, 80 per cent. It said it only belatedly realised that its data did not include pupils who were placed in full-time education immediately after their exclusion.

A DfE spokesperson says: “When any child is excluded for longer than five days, there is a duty on the local authority to ensure that they continue to receive a suitable education.

“The education must be full-time, or as close to full-time as possible. We are working closely with local authorities and schools, as well as providers of alternative provision, to ensure all children, including those who have been excluded, receive a high-quality education.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters