‘Fairer’ funding: is the money really going where you’d expect?

“Fairer funding” is the government’s mantra when it comes to explaining its controversial new approach to setting school budgets.

But new findings reveal how an apparently anodyne change to the government’s national funding formula plans will cause a “dramatic” shift that prominent education figures say is anything but fair.

A Tes investigation shows that the final version of the formula, which was published last month, will see many schools with low levels of deprivation among its pupils handed the biggest increases in funding.

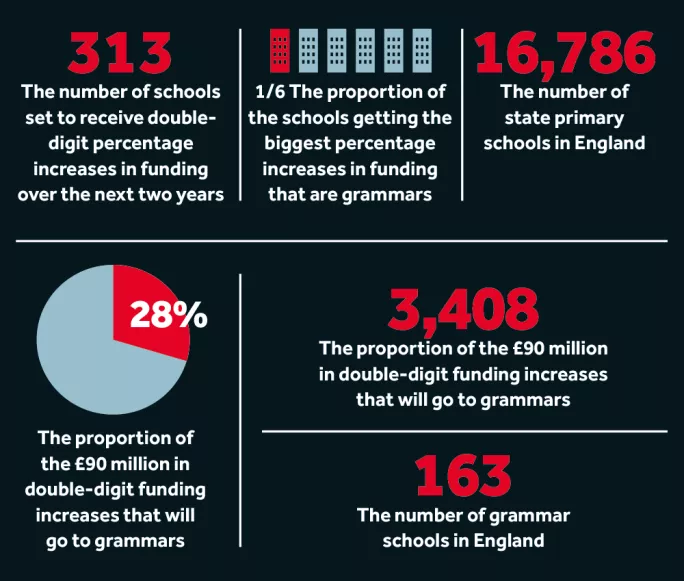

According to the analysis, grammar schools are 24 times more likely than primaries, comprehensives and secondary moderns to have their budgets increased by at least 10 per cent by 2019-20.

Of the 313 schools that will get a double-digit percentage increase to their budgets under the government’s new funding formula, 51 are grammar schools.

Grammar schools account for 16 per cent of the schools that will do best out of the new funding arrangements, taking 26 per cent of the extra funding. This represents a significant reversal of fortunes for a group of schools that has seen the spotlight drift away from it since the general election.

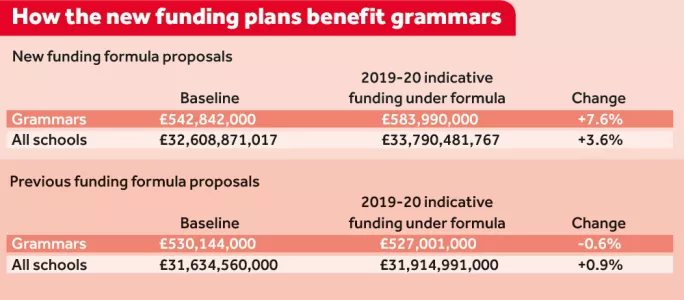

When the government first unveiled the proposed national funding formula, which would have resulted in many grammar schools losing out, it was dubbed a “funding betrayal” by the Grammar School Heads’ Association (GSHA).

The change is largely due to the fact that, although schools will have any annual budget increases capped at 6 per cent over the next two years, they will be allowed to go above this to reach “minimum” per-pupil funding: £4,800 for secondary and £3,500 for primary pupils.

The aim is to help those schools that, due to the demographics of their intake, receive little or no extra funding for the additional needs of pupils, such as those from deprived backgrounds, with low prior attainment or who speak English as an additional language.

The final formula also very slightly reduces the proportion of funds aimed at helping schools in the most deprived areas.

The minimum funding levels fail to reflect the different needs facing different schools; this is problematic when there is not enough money to go around, according to Mary Bousted, joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union. “The national funding formula was supposed to fund all schools fairly and according to their needs, but these figures show that the government’s failure to provide enough funding overall is failing to achieve that,” she says.

Bousted argues that many grammars will be “better protected than comprehensives and secondary moderns” as a result. She adds: “This runs counter to the government’s aims of reducing inequality, since grammar schools admit fewer children living in poverty, with low prior attainment or with English as a second language.”

‘Anything but fair’

Chris Keates, general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union, echoes these concerns. “The information that the funding may be privileging grammar schools over others requires urgent investigation as it appears to indicate the formula is anything but fair,” she says.

NEU’s assistant general secretary, Andrew Morris, warns that the system will leave schools with the least deprived intakes better protected, which many will see “as fundamentally unfair.”

But headteacher unions, while highlighting the need for bigger budgets, have cautiously welcomed the minimum funding levels for primary and secondary pupils.

Valentine Mulholland, head of policy at the NAHT heads’ union, said: “The impact on grammar schools is an unintended consequence of the minimum per-pupil funding. As grammar schools tend to be smaller and have low levels of additional need, they are likely to be relatively poorly funded in current funding formulae.”

Grammar school heads agree that the disparity is because schools that have been traditionally less well-funded are being brought up to the same level as other schools.

As David Scott, headteacher of Kesteven and Grantham Girls School - which is in line for an 11.9 per cent increase - puts it: “There are a disproportionate number of grammar schools among those schools that have repeatedly for many years received funding well below the basic minimum per-pupil funding level.”

The NEU’s own research shows that grammars are not immune to the budget squeeze, and suggests that they will suffer a real-terms loss of £25 per pupil between 2015 and 2020. This equates to a 1 per cent drop in real terms, taking account of rising costs - lower than the 4 per cent cut facing the average secondary school.

It still leaves grammars with lower per-pupil funding than other secondaries on average - £4,697 by 2020, compared with £5,274 for non-selective secondaries.

Jim Skinner, chairman of GSHA, says: “This is not a grammar school issue, this is a low-funded school issue...there is a minimum per-pupil funding level below which a school simply can’t operate.”

And the latest GSHA newsletter says the fact that the minimum per-pupil levels do not take account of higher labour costs in some parts of the country “is a problem for some of our schools in outer London”.

Clive Sentance, the principal and chief executive of Alcester Grammar School in Warwickshire, which is expecting a 10.4 per cent rise, says: “The proposed increase will simply raise us to the minimum level of per-capita funding.

“Whilst we welcome any additional income, the fact remains that even with this rise we will be one of a great many schools funded at the lowest possible rate.”

A Department for Education spokesman says: “The National Funding Formula makes no distinction between types of schools.

“Some institutions that have been historically under-funded because of the regional disparities in the previous system will see bigger increases than others. The majority of these are not selective schools.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters