A fighting chance for ‘unmanageable’ students

You might think that the last thing you’d want to do with kids at risk of exclusion for violent behaviour is to show them how to throw a punch properly.

But the real surprise of The Boxing Academy - the winner of the Tes Schools Award for alternative provision school of the year - is that many of its streetwise, tough students aren’t keen to learn how to fight.

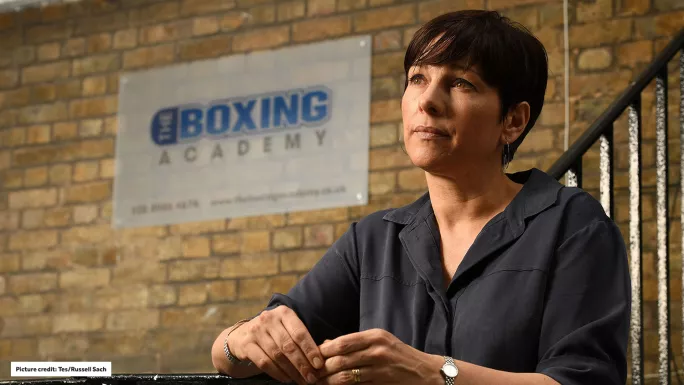

“Ninety per cent of the kids say they don’t like boxing,” says principal Anna Cain. “Most of them don’t do any exercise. There’s a lot of sitting on the sofa playing PlayStation.”

That isn’t necessarily out of laziness, Cain suggests. Many of them face confrontations with territorial postcode gangs if they stray out of their neighbourhood to use leisure facilities that middle-class families around them take for granted.

But if they’re reluctant to get in the ring, how does boxing inspire them to re-engage in education?

The academy’s results certainly seem to suggest that many of its students’ lives take a new direction in this cramped building down a side street in Hackney, East London.

Their behaviour, which had been unmanageable in mainstream settings and even in PRUs, was described by Ofsted inspectors last year as “outstanding”.

Every student at the academy continues education or training after they leave at 16 and their grades are above average for comparable schools nationally, with 15 per cent getting A* grades in the academy’s strongest subject, PE.

“Boxing has a long history of being exceptionally effective with disaffected teenagers,” Cain says. “But it’s almost not about the boxing; it’s about relationships.”

It was a close relationship that brought Cain to the job of principal: she was working in a corporate career when her son was excluded from his school and referred to the academy’s former premises in Tottenham, North London.

That experience means she knows the “shattering” toll that exclusions can take on families. Amid all the stress and extra meetings in school, she lost her job. The academy asked her to come in and take some ICT lessons, and the rest is history.

“It’s a school first and foremost: there’s a timetable, we have teachers, we do GCSEs,” Cain says. Students take exams in English, maths, RE, citizenship, science and art, as well as a Health and Fitness V Cert, which replaced the PE GCSE after an unwelcome specification change. “It’s all very ordinary, but the ratio of staff in this school is very different to mainstream.”

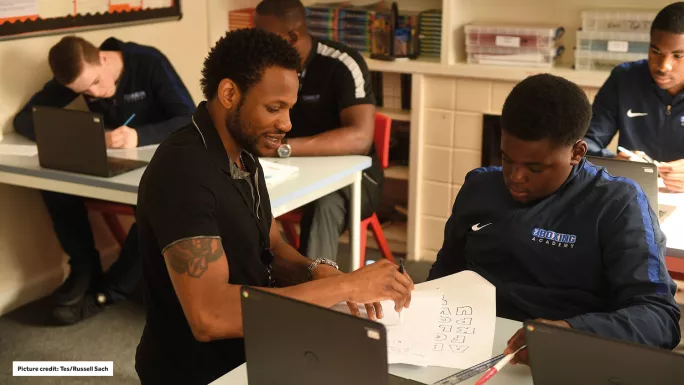

There are five classes of eight students - mostly boys, with a handful of girls. They have five teachers and eight of what the academy calls “pod leaders”. Dressed in black, wearing earpieces like bouncers, these are the competitive boxers turned educators that make The Boxing Academy unique.

They coach the daily boxing lesson, then follow their students into their other lessons as TAs, mentors and behaviour co-ordinators. Cain says that the person most responsible for the way they work is the head of boxing, Jermaine Williams.

Williams has a life story many of the students can relate to. An undocumented immigrant from Jamaica who arrived in South London as a child, he fell in with the wrong crowd, one that committed robberies, carried knives, fought in the street and sold drugs.

A spell in Feltham Young Offenders’ Institution, where another inmate tried to strangle him, was his wake-up call. On the outside, he resolved to change his life, volunteering and eventually joining a boxing gym nearby.

He describes the coach there as a figure like The Karate Kid’s Mr Miyagi - small enough that Williams mistakenly thought he could beat him in the ring. The coach soaked up his punches before immobilising him with a single blow to the ribs: it was an unforgettable lesson in the power of patience and discipline.

“Without me even knowing, it was changing my whole perception of life. The people in the gym were like brothers and sisters, and the coach was like the dad, giving me structure,” Williams says. “This was the first time I felt like I belonged somewhere.”

A sense of belonging and patience are two of The Boxing Academy’s tools. That patience even extends to the rare threat of violence.

With the boxing staff trained in de-escalation, dodging punches and even taking them, the academy can afford not to exclude students for assault. That ends up removing much of its power - they even let students settle arguments with sparring under controlled conditions.

“If you’re struggling to access the curriculum and you kick off, you get sent home for five days. It’s like a reward for these kids and they learn how to play that system. We don’t do that,” says Cain.

For Williams, working with the behaviour of these kids is more like the psychological battle in boxing than the physical struggle.

“You have to be very disciplined, that’s what boxing teaches you,” he says. “You have to be patient and clever. It’s like a game of chess where you try to outsmart your opponent. You have to be quicker, because they always try to get one over on you.”

Unable to make use of their usual disruptive strategies, the students knuckle down, accepting punishments such as 25 press-ups or being forced to do the washing up. Every detention also comes with a heart-to-heart talk.

Eventually, students say that this mix of discipline and compassion begins to change them. Ali Delidogan, 15, is one of them: excluded for fighting from his old school, he asked to come to The Boxing Academy instead of a PRU.

“The pod leaders are always with you, throughout the day. As soon as you make a mistake, they don’t just shout at you or give you a punishment - they’ll pick up on it. If you do get a punishment like push-ups, they’ll just be there, talking to you,” says.

“Since I’ve been here it’s made me reflect on what I can actually do, instead of wasting my time. I’m not perfect right now, but I’ve changed a lot since I’ve been here. I’m still working on it.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters