Fighting the fear

Yes, I’ve felt fear in this job. Fear of the next learning walk or observation. Fear of anyone walking into your classroom to tell you you’ve done something wrong. Fear the minute you wake up knowing you have too much to do. Fear driving to work knowing that just the smell of the building will set your heart racing. Fear that you will end up in a psychiatric hospital. Fear that you will lose your job, home and family.”

No one talks about fear as much as they used to in education. Not really. The profession talks a lot about workload, a lot about accountability and stress, a lot about pressure. But as the above post on the Tes forum suggests, in response to a question about whether teachers still felt fear, those other terms may all be euphemisms for, or by-products of, what is really driving the problems in schools: teachers are scared.

“We don’t talk about it directly now but it is there and it underpins everything,” says Mary Bousted, general secretary of the ATL teaching union. “The reason it manifests as workload or as worries about accountability is that these are the real-world impacts of that fear.”

And at this time of year, as we move into accountability season when young people from all levels of education are assessed for progress and teachers are assessed on that progress, those real-world impacts can become even more acute.

“Fear didn’t cover it,” reads another post. “I felt sick with terror sometimes. Terrified that my results wouldn’t be good enough, terrified I couldn’t get the children [to the level] the school hierarchy demanded.”

It’s not just a few teachers at the sharp end of things who are affected. Darren Northcott, national official for education at the NASUWT teaching union, explains that “members report that fear and anxiety increasingly characterise the working lives of many teachers”.

And Bousted adds that fear is a key contributor to retention problems in teaching. “It is fear that is causing that loss of teachers and causing that retention crisis,” she insists.

So it’s important that we look at fear in education - what drives it, what it does to teachers and how to get over it. Because fear is not just an unfortunate side effect of a career in education. It is a destructive force that endangers teachers’ health, stops them from performing at their best and, ultimately, makes them want to leave.

But what if some of that fear is actually within teachers’ control? What if it wasn’t all the government’s fault, but perhaps partly schools’ fault? And what if individuals could be doing more themselves, too?

The drivers of fear in education are complex and nebulous. At a basic level, this is a profession of people who want to do well. They care about their job. And it is a very important job - being responsible for educating the next generation is, by its nature, scary. So a little bit of fear - of not being good enough, of not doing well enough - is perhaps natural.

But what we are talking about in today’s teaching profession seems to be more than teachers being a little anxious. It is much worse. And the factors that contribute to it are not usually internal - coming from a teacher’s hopes and ambitions and sense of responsibility - but external, pushed on to teachers by others.

Northcott believes that a big offender is unreasonable performance objectives.

“We too often see teachers being set objectives relating to pupil performance outcomes only,” he explains. “In conversations I have with teachers, that way of holding them to account is pretty near top of the list of reasons they feel fear and anxiety.

“The school environment, resources, and home lives of pupils are all relevant to how pupils perform. But still your pay, perceptions of your competence, and even your continued employment are determined by these outcomes over which you do not have exclusive control.”

Inspection is another common trigger, says Bousted: “Ofsted has tried its best but everything that comes with Ofsted naturally creates fear - people genuinely fear for their jobs if they have a bad inspection.”

Helena Marsh, executive principal at Linton Village College in Cambridgeshire, who is part of education thinktank the Headteachers’ Roundtable, agrees.

“I would say fear about a poor inspection outcome is one of the most significant factors that causes anxiety among teachers, because so much rests upon that judgement,” she says. “Schools can end up on tenterhooks, wanting to be permanently ‘Ofsted-ready’. You get teachers thinking, ‘Should I take my display board down today? What if we get the call?’ It’s unhealthy.”

Excessive workloads, pupil and parent complaints, capability procedures, syllabus changes and lesson observations are some of the other key drivers of fear that teachers report. It usually arises where repercussions for failing to do enough or the “right” thing are potentially severe.

The clipboard approach

What can exacerbate these problems is that it’s easy for an “us versus them” culture to develop between senior leadership teams and teaching staff in schools.

“The trouble is that you have school leaders who are scared, and that fear then filters down to teachers,” says Bousted. “It creates a profession of compliance rather than one of collaboration.”

Many teachers report being scared of managers. One forum user describes how “every day is like an inspection, with our own personal inspectors walking around, clipboard in hand, picking fault after fault”.

That “clipboard” approach is down to fear, pure and simple, says Marsh.

“As heads, we are the buck-stoppers and there’s an increasing sense in the current high-stakes accountability climate of, ‘You’re only as good as your last GCSE results or inspection,’” she explains.

“In three years, at least three heads in my area have, following a negative inspection or poor results, vanished. That tends to have been the governing body’s decision if they feel the head hasn’t served the school well. That fuels fear.

“How reasonable schools’ quality assurance practices are varies - and it can depend on how fearful people are of justifying the standard of education being delivered. You may have schools doing lots of paper trails or work scrutiny because there’s desperation to evidence everything.”

Once upon a time, climbing the ladder to headship might have increased job control and so diminished fear, but Northcott believes that’s less often the case today.

“With the reorganisation of much of the school system into multi-academy trusts, those trusts in many cases control what happens in each school. So school leaders’ agency is beginning to decline because their responsibility is simply, in many cases, to ensure that what others want to happen in their school is delivered.”

Some forum users also reported inexperienced candidates being promoted to management roles, without appropriate training to handle the pressures.

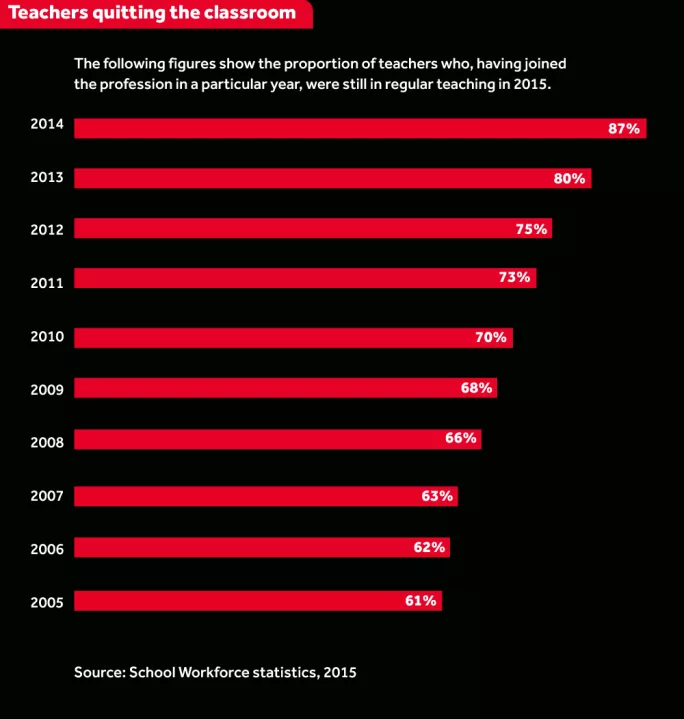

Clearly, fear is making teaching an undesirable career option. It was reported by Tes in October (bit.ly/NewTeachersQuit) that nearly a third of the teachers who entered the profession in 2010 had dropped out within five years (see graphic, below).

And, as Bousted says, a key reason for teachers wanting to leave the profession is fear. That’s because of what fear does to a person and, more specifically, how it can impact on teachers. Indeed, when you look into the science of fear, you begin to see how destructive a state of constant fear can be.

“Fear is the physical and emotional response to threatening situations,” says Dr Susannah Murphy, senior research fellow in the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

“Our brain is optimised for the fast detection of information that might signal danger. It responds by initiating a cascade of reactions. For example, adrenaline is released, increasing heart rate and blood pressure, and cortisol is released, which mobilises energy to muscles. This prepares us for attack, flight or other behaviours in response to the threat.”

Anxiety is a close cousin.

“Fear is the response to specific, actually threatening stimuli; anxiety is elicited by potentially dangerous but unspecified future threats,” explains Murphy.

So if you dread inspection, anxiety may be felt when you think Ofsted might call. Fear may kick in when face-to-face with the inspector.

While the body’s response to fear or anxiety can be positive in the short term - for example, motivating us to meet a deadline - it can be damaging if sustained.

“Long-term secretion of glucocorticoids [eg, cortisol] can have damaging effects, including increased blood pressure and suppression of the immune system,” says Murphy. “Adverse psychosocial work environments are also associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease.”

There is also a positive correlation between the number of stressful events in a person’s life and their probability of developing a psychological disorder, explains Murphy.

“People with generalised anxiety disorder [GAD], for example, experience constant worry and continuously predict, anticipate or imagine negative events. They have physical symptoms such as muscle tension and agitation that lead to fatigue, poor concentration, irritability and sleep difficulties. GAD has an impact on their ability to function socially or professionally.”

Ironically, teachers who know all this may end up adding “health” to their list of things to worry about. Anyone who feels that theirs is being impacted upon should see their GP.

It’s not just teachers, but also their teaching that is affected.“Fear has led to a reluctance to innovate, take risks and to be creative,” says Bousted.

Marsh agrees, stating that fear drives conformity. “It feels like the ‘KFC-ification’ of education - everyone follows the Colonel’s recipe. Either teachers have forced it on themselves because they think that’s what people want to see, or there’s been instruction within the school about how lessons need to be structured and how marking is done. I think consistency can be something everyone strives for - but why? Is it essential we all mark in the same colour pen? Is that helping learning? Or just to make us feel in control?”

Where creativity dissolves, both students and teachers lose out, argues Stephen Munday, chief executive of The Cam Academy Trust and executive principal of Comberton Village College in Cambridgeshire.

“Often it’s only by doing something different - by being prepared to make mistakes - that you progress,” he says.

“Apart from anything, creativity is fun,” Munday adds. He believes the best models are where teachers feel secure and supported enough to work in small groups, testing ideas on each other.

Fundamental teaching styles can be morphed by fear, too, argues Dr Eleanore Hargreaves, reader in learning and pedagogy at the UCL Institute of Education.

“Many schools have gone back to an authoritarian style of teaching recently because of fears about accountability, meaning they favour a controlled classroom environment. However, in authoritarian classrooms children tend to be more fearful, less creative, ask fewer questions, be scared to answer questions, and are not encouraged to be critical,” she says.

Northcott notes that it can be disturbing for teachers when they feel driven down this path: “Teachers feel incredibly responsible for the young people they teach. So if they don’t have the control to do what they think is right, in their professional judgement, to help those pupils succeed, I think that does create fear and anxiety.”

How to fight the fear

So, what can we do about the disruptive role fear is playing in the lives and careers of teachers? Fighting the fear requires action on multiple levels, from things the individual teacher can do right up to system-level changes.

Indeed, while it is tempting to lay all the blame at the government’s door - and clearly there is a substantial amount to deposit there - many claim that, actually, individual teachers and schools can do more than they currently are doing to beat fear. And though an individual teacher may be trapped in a system of fear, there are things that can be done to offset some of the impact. Dr Victoria Galbraith, a registered counselling psychologist, suggests taking a critical look at negative thought patterns.

“Negative thinking has the propensity to take over, so one could begin by challenging this thinking; for example, asking questions such as, ‘What’s the worst thing that can happen in this situation?’ followed by, ‘What’s the likelihood of that happening?’” she says.

The idea is that this can help to reframe worries, as you may recognise that while the outcomes you fear are possible, they are also highly unlikely (ie, that you’ll get sacked because you didn’t mark in the exact right shade of red pen).

Another useful question that Galbraith suggests asking is: “Have I ever been in this situation before and have I learned anything from previous situations that could help me now?” Plotting a practical strategy to tackle your concerns can help you to feel more in control.

But the thing that is most crucial, stresses Galbraith, is not letting your thoughts become the boss of you.

“Often, we allow our mind to be taken over by planning, worrying and so on. A top tip here would be to remember that thoughts are not necessarily facts. Recognise any thinking as mental events that can be observed rather than living your life through the thinking,” she advises.

So if a negative thought crops up - such as, “Tomorrow’s inspection is going to be a disaster” - note it, accept that it’s just a thought, then try to set it aside.

In the heat of the moment, when you are faced with a situation that provokes fear, Galbraith recommends trying the “three-minute breathing space” - a mindful meditation on your breathing (which can be found at bit.ly/ThreeMinBreathe).

“It’s a great technique that can be used to help ground you in the moment. By focusing on your breathing you’re activating the parasympathetic nervous system, which lowers amounts of stress hormones [in your body]. It also takes the focus away from negative thoughts before they spiral out of control,” she explains.

Mark Enser, head of geography at Heathfield Community College in East Sussex, agrees that teachers can begin the process of reducing fear themselves.

“Teachers can sometimes be their own worst enemy,” he says. “It’s a stressful job and easy to stoke a culture of fear. There can be oneupmanship where everyone boasts of the long hours they put in. We need to start boasting that we had an evening off, relaxing with our families. That is something to be proud of.”

Social media can play a helpful role here, with the #teacher5aday and #optimisticed hashtags promoting this positive behaviour.

“I think that teachers should be brave and vote with their feet,” says Enser. There are amazing schools out there. We don’t have to stay in those that promote a culture of fear.”

At a school level, there are numerous things that can also be done to offset fear, according to heads.

This process starts with the actions of the headteacher, says Munday.

“It’s my responsibility to ensure, as much as I am capable, that there isn’t a culture of fear in organisations that I have some responsibility for,” he explains. “I think that’s one of the most important parts of my role. I think you’ve got to have a strong, genuine belief in what you’re trying to do and what education is about. You can be mindful of accountability measures without them driving you to do ridiculous things. There’s no harm in saying out loud: ‘We’re working together, doing a good job. Thank you for what you are doing. When I pop into a lesson, I’m not trying to catch you out.’

“Of course, don’t then pull people up all the time because they’re not doing things precisely the way they’re supposed to.”

Taking away the cliff edge

Marsh believes demonstrating that it’s OK to fail is another powerful move.

“I think you should model failure, as a headteacher or senior leader, by sharing things that haven’t been successful,” she says. “That way, failure doesn’t become this cliff edge, where people feel they can’t admit to it.”

She also believes leaders need to speak out. “I’m quite vocal as a head, for example, by being a member of the Headteachers’ Roundtable. I think that it’s our responsibility to raise our heads above the parapet and challenge things that aren’t working effectively in education.”

Another area that schools should focus on is performance management, says Northcott. He and many others would like to see national safeguards in place, stopping schools from judging performance on pupil outcomes alone.

“We advise members to raise it with their managers if they feel they’re being set unreasonable objectives,” he explains. He would encourage teachers to speak to their union if this is not addressed, or if other matters are contributing to workplace fear.

Enser is testament to the difference that avoiding results-driven objectives makes.

“I teach in a school that does not have a culture of fear,” he reveals. “No one is judged solely on a set of exam results. Last year we saw a slight decline in the geography results. I had regular meetings with the head to discuss what we, as a department, were going to do. These meetings at no point created fear. I never felt blame was being attached. They focused on solutions and it was a team effort. We went on to achieve our best-ever results.”

One school has pushed this even further by scrapping objectives altogether. The journey of Hiltingbury Junior School in Chandler’s Ford, Hampshire, is detailed in this issue (see “Why you should free staff from the shackles of specific targets”).

Interestingly, there are many who think the fear caused by Ofsted is also an issue that can be tackled at a school level, though not all agree. “We need a wholesale review of school accountability to provide a more humane and intelligent way of judging schools, looking at peer review and other vehicles for self-evaluation,” says Marsh.

Munday feels that it is not Ofsted causing the issues - rather, it is how schools interpret and view Ofsted that is the problem. “My view of Ofsted is: the biggest single problem with it in practice is the interpretation within schools, allowing it to be the fear factor,” he says.

Hargreaves agrees that how schools deal with inspection could be improved, and advocates a more open approach. “I think it’s beneficial when teachers say, ‘This is what we have to do for the inspection. Let’s talk about how we’re going to do it and how you feel about it.’ This will give them some control, reducing fear.

“It’s [similar to how we should talk about exams in education]: ‘This is what we need to get good at for the test because tests are important,’ but also talk about the relevance of the subject beyond the confines of the curriculum so kids get to be critical about it - and also take a more critical view to testing itself, recognising there’s more to learning.”

To be fair to Ofsted, it has certainly been trying extremely hard to reduce the fear that its inspections cause. Sean Harford, Ofsted’s national education director, says busting inspection “myths” is a priority.

“It’s really important to get this message to teachers: we have no preferred style of teaching. There’s no preferred style of learning. There’s no preferred style of marking or volume of marking. There’s no predetermined volume of work all children should produce,” he says. “You shouldn’t be afraid. Do what you do - day in, day out - and you will be fine because that’s what you’re judging to be best for your students.”

He also highlights the fact that there is a complaints procedure if schools feel an inspector has not behaved appropriately.

And yet, while fear may well be partly in the control of individual teachers and schools, above all this sits the accountability system imposed by the government. However hard schools, individuals or Ofsted try to reduce the fear in education, there are still league tables and high-stakes exams, and there is still a relentless narrative of underperformance, of schools not being good enough, of those in education “failing”. That stance tends to colour everything else.

Yes, a little fear is healthy; it drives humans to want to do more and it can be motivating. Yes, schools and individuals can better manage causes of fear. But if the government does not manage fear, too - if it does not begin to address what is causing a profession of more than 500,000 people to go to work scared - then, ultimately, fear will remain. And as we have seen here, the result of that is teachers leaving the profession, or those who stick around suffering in terms of both their teaching and their health.

As we come to the key accountability period of the year, schools will see those impacts first-hand once more.

Jessica Powell is a freelance writer

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters