Have targets, testing, tables and Ofsted had their day?

When secondary league tables were published this year, the headline figures made uncomfortable reading for the government.

Schools missing the floor standard - up. Pupils entering and achieving the English Baccalaureate - both down.

Of course, the Department for Education had its caveats and excuses prepared. The rise in the number of schools below the standard was primarily because of changes in statistical methodology, officials told journalists.

But then they turned their attention to explaining away the disappointing EBacc figures. And that was when school accountability jumped the shark.

They pointed out that while fewer pupils might have entered and achieved the “full EBacc”, there had been an increase in the proportion of students entering and achieving “four pillars of the EBacc”.

But there is no such measure as the “four-pillar EBacc”. The EBacc covers five core academic subjects and was meant to be the gold standard for measuring pupil and school attainment. Michael Gove introduced it when he was education secretary precisely because he believed that previous performance metrics had not been sufficiently robust.

Officials’ desperate on-the-hoof attempt to redefine and water-down this totemic quality mark wasn’t just a The Thick of It-style example of how not to bury bad news.

Trouble brewing

The confected “four-pillar” EBacc is symptomatic of a much wider malaise that has gradually engulfed the entire school accountability system. Problems have been allowed to go unchecked and bubble away for years. They have slowly undermined all aspects of the accountability infrastructure, from tables, targets and testing, to Ofsted and the sanctions that the DfE uses when schools fail to meet its standards.

Now they are all beginning to boil over at the same time:

• Schools and academy chains are starting to simply ignore a key DfE performance target.

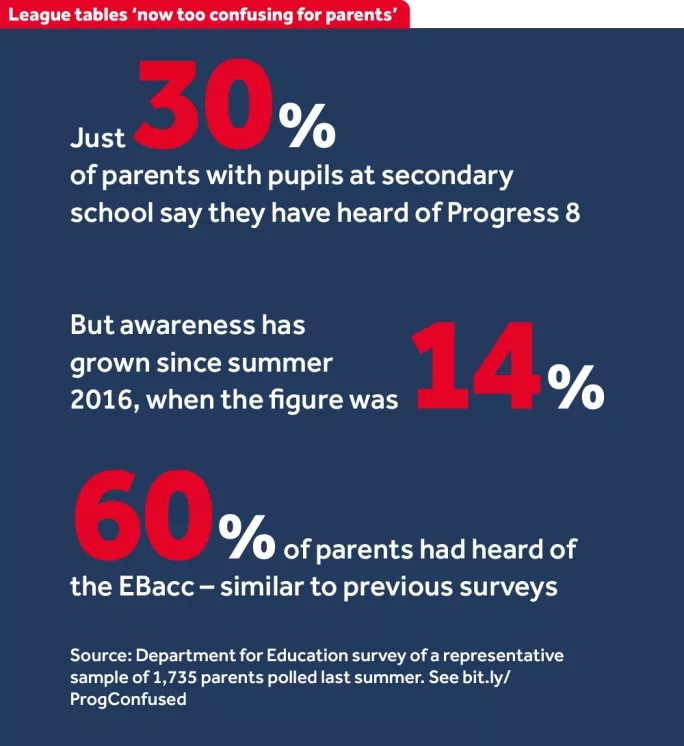

• We now have a headline secondary school performance measure - Progress 8 - that few parents have heard of, let alone understand.

• Schools are closing because the government cannot find an academy chain that is prepared to take them after they have been judged to have failed under its accountability measures.

• Serious questions about the validity and reliability of Ofsted judgements that determine schools’ fates may never be fully answered, according to the inspectorate’s own head of research.

• The recent shambolic “reform” of primary assessment looks likely to continue with experts warning that the government’s new baseline measure won’t work.

In short, the system that central government has used for more than a quarter of a century to get schools to do what it wants is now falling to pieces.

Ministers had got used to the fact that when they pulled certain levers, heads, who had become highly attuned to the necessity of doing the DfE’s bidding, would jump.

Now, when ministers pull those levers, increasingly, they find that nothing happens. Or worse still - as with primary assessment - they get an angry reaction from teachers who simply can’t take any more.

So, has school accountability finally reached the end of the line?

Warning signs

Once upon a time, what happened inside schools was regarded as a “secret garden”, with no school performance data published at all. Then came the revolution sparked by Conservative education secretary Lord Baker, which brought the introduction of national primary testing, GCSE league tables and Ofsted in the early 1990s.

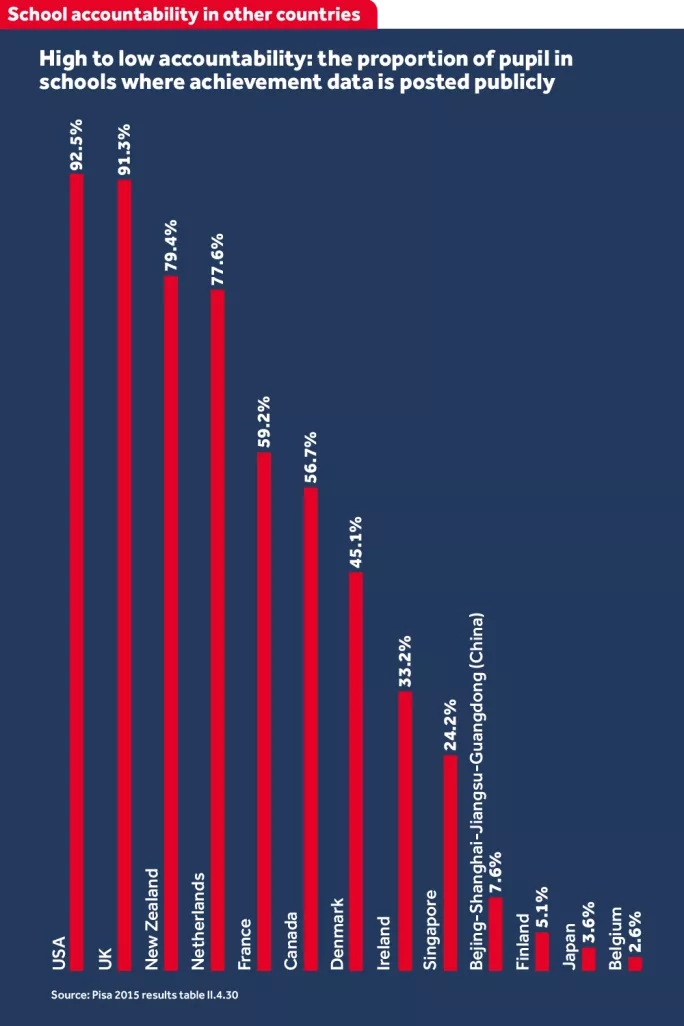

Ever since, our education system has been run on the basis that if schools are held to account for their results then they will improve faster. And, the argument goes, if a school is failing to provide a decent education, it will be identified early and processes will quickly kick in to correct the underperformance.

Accountability metrics are also supposed to give parents an indication of the quality of local schools, allowing them to make informed choices about where they send their children.

However, there have long been signs that all is not well with the system.

The high water mark of central government’s favourite method of school accountability - top-down targets - came early on. The first key stage 2 Sats, taken in 1995, showed that less than half of pupils reached the “expected” standard in numeracy and literacy.

New Labour entered government determined to improve on that, and by 2000, it had used test targets to drive some seemingly impressive improvements. The intervention was lauded as a success for years. But, in fact, results soon plateaued - and not long afterwards parallel data not subject to the same high-stakes accountability pressures raised serious questions about how real the progress had been.

The problems associated with school accountability have only multiplied since then. Growing numbers of secondaries relied on pseudo-vocational “GCSE-equivalent” qualifications - of dubious real-world worth to the pupils taking them - to bolster their league table positions.

Meanwhile, curriculums shrank as schools began to focus on what was tested, and increasing time and resources were dedicated to preparing for all-important do-or-die encounters with Ofsted.

‘Hyper-accountability’

But perhaps the most pernicious impact of accountability has been the pressure placed on teachers and school leaders. A new phrase has entered the English educational lexicon - “hyper-accountability” - to describe the surveillance culture that now exists in schools.

Tim O’Brien, a visiting fellow at University College London’s Institute of Education who previously worked as Arsenal Football Club’s first team psychologist, says teachers are suffering “fatigue” from a “hyper-accountability industry” that has left them in a “state of manic vigilance”.

While the government has batted away such claims in the past, there are now indications that it, too, is facing up to the cumulative impact of years of high-stakes accountability. In October, schools minister Nick Gibb admitted that schools had been put under too much “football manager-type pressure” to reach floor standards.

While Gibb said that the education system still needed accountability, he argued that the “mere publication” of school results was sufficient to provide “the pressure that will raise standards”. However, one minister can’t reverse a decades-long trend in educational policy with a single pronouncement.

And what was already a vexed issue has been exacerbated by a sense that the goalposts are constantly shifting.

When the number of schools below the floor standard increased this year, the DfE attributed this to changes in the way it calculates its Progress 8 measure, which were, in turn, necessitated by the new 9-1 GCSE grading system.

The DfE consequently told regional schools commissioners and local authorities that they shouldn’t rush to take action against schools that had fallen below the standard for the first time in 2017 - a sign that the department’s confidence in its own ability to separate the wheat from the chaff had been shaken.

EBacc confusion

The goalposts have also shifted with the EBacc. Originally, the government set a target for 90 per cent of pupils to take it by 2020. The target has been changed twice since, and currently sits at 75 per cent of pupils by 2022.

Given that the target has been fiddled with so much, it’s not particularly surprising that one multi-academy trust has broken ranks and suggested that as few as 15 per cent of pupils at some of its schools could be entered for the EBacc.

But it’s not just secondary accountability measures that are in disarray. For the past two years, the DfE and Ofsted have said that writing assessments in KS2 will not be used to judge schools owing to a lack of confidence in the moderation process. The government has announced that KS1 tests will be scrapped, but there is considerable scepticism about its idea of returning to baseline assessments.

One of the ironies of the current accountability framework is that as the government has implemented waves of reform aimed at removing its worst inequities, it has ended up with an ever more complex system. This weakens one of the intended purposes of accountability - to influence parental opinion and, therefore, school behaviour.

Ruth Lowe, external affairs manager at Parentkind - formerly known as PTA UK - thinks that Progress 8 is “an incredibly complex measure to understand”. “It took me a good few weeks even to read through all the detail and process and think about how I can make this clearer to parents,” she says.

Parents can frequently be left with “misconceptions” about what the indicator is saying, warns Lowe. “I tried to explain Progress 8 to a parent friend of mine, and talked about the minus scores. She said, ‘Oh, so does that mean that school is making my child dumber?’” (Progress 8 is, of course, a relative measure, so the answer is, “Probably not.”)

The existence of two separate secondary metrics, Progress 8 and EBacc - covering different baskets of subjects - only adds to the confusion. This was tacitly recognised by Rachel Atkinson, the DfE’s head of inspection and accountability, at a recent event. “Why do we have both?” she asked. “You might say we wouldn’t have started here. I think that’s pretty fair to say.”

Actually, under Gove, there was a deliberate decision to introduce a multiplicity of headline measures. The thinking was that the more measures there were, the harder it would be to game them. Introduce enough new ones and in the end schools that wanted to play the system wouldn’t know what to focus on. They would have no choice but to forget about league tables and just do their jobs. But those behind this theory forgot to factor in how confusing the result would be for parents.

Ofsted’s challenges

Of course, testing, targets and tables are only one half of our school accountability system. The other - Ofsted - has faced its own challenges. In 2013, Professor Rob Coe, the director of Durham University’s Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, questioned whether inspection led to valid judgements.

While Ofsted carried out a small study on its short inspections last year, there is still a paucity of research on its reliability and validity.

To cap things off, when schools are found wanting by the inspectorate, the tools that are supposed to turn around their underperformance no longer seem to be working.

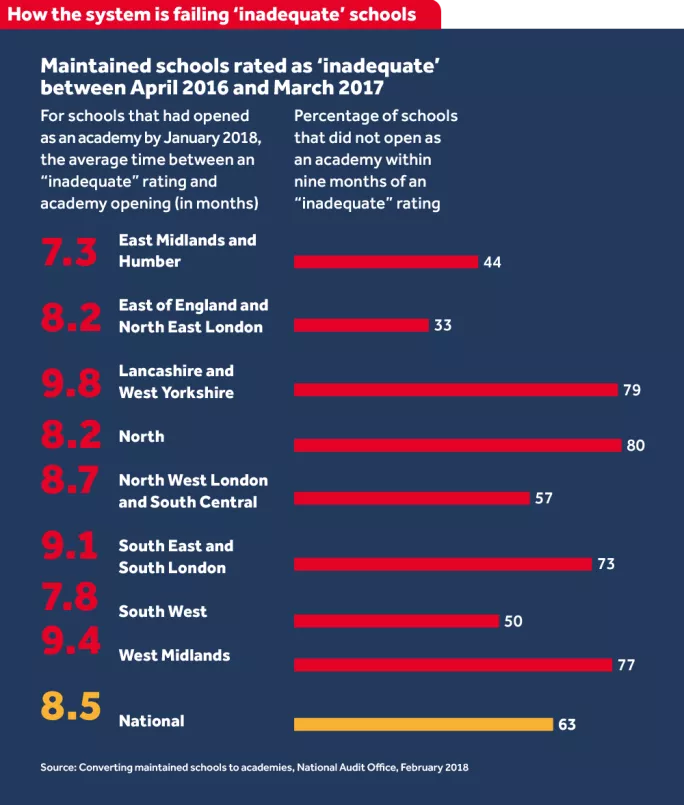

A damning report by the National Audit Office last month highlighted a shortage of sponsors for schools judged to be “inadequate”.

Given this catalogue of problems, it’s not surprising that calls are now being made for wholesale reform of the system.

Last week, the NAHT heads’ union launched an independent commission on accountability. “We’ve described the current accountability system as high-stakes, low-trust,” says Nick Brook, the union’s deputy general secretary. “In a nutshell, it’s doing more harm than good.”

The Liberal Democrats beat NAHT to the punch, publishing a policy paper that suggests scrapping Ofsted and Sats, overhauling league tables and abolishing regional schools commissioners. However, once you take a closer look, the party proposes resuscitating many of these structures in a new guise. Ofsted, for example, would be replaced with “a new HM Inspector of Schools, drawing on the best traditions of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Schools”. A critic might accuse the Lib Dems of wanting to rearrange deck chairs.

The government could go for the nuclear-option, and follow Wales by demolishing its accountability architecture. But the Welsh experience - it is currently the worst-performing UK nation in the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) tests - is not particularly encouraging.

Perhaps the most likely scenario for our wobbling accountability system is a continuing policy of makeshift fix and fudge. Supporters will say it’s not a complete litany of despair - they might, for example, argue that the phonics check introduced in 2011 helped to move England up the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study table.

Fundamentally, our addiction to accountability is a symptom of society’s low appetite for risk in education.

Or, to put it more critically, an unwillingness to trust schools to get on with the job of teaching children without being subject to oversight and performance management.

Is the public ready to let teachers return to the “secret garden”? For as long the answer to that is still “no”, it seems accountability will be here to stay.

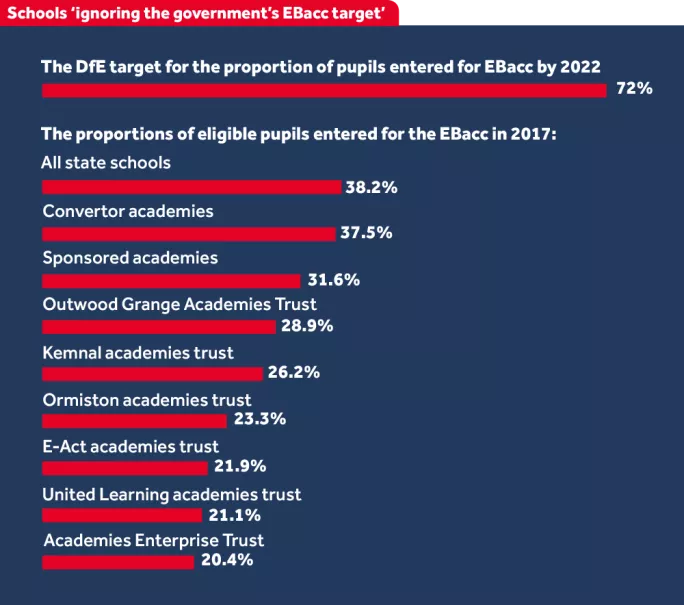

Schools ‘ignoring the government’s EBacc target’

Ministers have made increasing the number of pupils who are entered for its English Baccalaureate measure a key, high-profile target.

But it is now emerging that a significant number of schools may simply ignore it. One of England’s largest academy chains - Greenwood Academies Trust - has discussed plans to put as few as 15 per cent of pupils forward for the EBacc.

The trust has told Ofsted that it wants to “rebalance the EBacc entry” at its schools, according to board minutes obtained by Tes.

Whether it has been emboldened by the steady watering down of the government’s goal - from a target of 90 per cent of pupils sitting the EBacc by 2020 to 75 per cent by 2022 - is unclear.

But Greenwood schools are not the only ones that appear likely to be giving this headline accountability target, first announced in the 2015 Tory manifesto, short shrift. It has certainly failed to galvanise the system, with the proportion of pupils entering the EBacc actually decreasing by 1.5 percentage points since 2016.

At least one other large multi-academy trust is thought to be sympathetic to the idea of cutting EBacc entry at some of the schools it runs, Tes understands, and many trusts remain an extremely long way off hitting the government’s target.

Are these academy chains using their autonomy to make a stand against the target? If so, their stance could well find support among heads who fear that subjects - such as art, music and PE - are being sidelined as a result of the EBacc.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says that his members feel an “increasing sense that the range of subjects that lots of us think are important are being marginalised”.

The union leader also questions how the Department for Education will enforce its targets, saying that the delayed deadline showed a “pragmatism in government that they don’t think it’s going to be hit any time soon”. The DfE did not respond to Tes’ question about how it planned to enforce the target.

But a spokesperson said that the department was “clear that we expect all schools to offer options in addition to the EBacc, so that pupils have the opportunity to study subjects that reflect their own individual interests and strengths”.

Charlotte Santry

New primary baseline assessment ‘unworkable’

Experts have warned that the latest Department for Education plans to fix the increasingly troubled primary accountability system come with built-in errors and will not work.

The government is pressing ahead with plans for a baseline assessment of four-year-olds as they start in Reception class, to use as a starting point for measuring progress.

The project has been backed, in principle, by some headteachers. But Greg Watson, chief executive of the assessment company GL Assessment, has warned that they may find the progress data is not as clear-cut as they think it will be.

“There is a natural level of error,” he says. “People may get the year wrong in a date of birth or there may be data missing. Pupils move around. They may leave infant schools and go to junior, or leave England, and it is hard to make sure the data quality is right.

“Headteachers may find themselves pleading with Ofsted that they don’t have the same pupils they started with, or they can’t match all their pupils, so the data is incomplete.”

Mr Watson says there are three key challenges: matching the pupil data accurately in the first place, keeping track of the data as pupils move between schools, and, in cases where pupils have moved, deciding how much credit each school gets for progress.

“It would take a big effort to improve the quality of the data,” he adds. “Even matching 98 per cent of pupils is not 100 per cent. I don’t expect 98 per cent reliability on my credit card statement. I expect my bank to be measuring that very accurately. This is about pupils making progress and, as a head or parent, I’d be shooting for 100 per cent accuracy, but I think that will be a stretch.”

The DfE says that an “extensive pilot” will ensure baseline data is “accurate and reliable”.

Meanwhile, Early Excellence - a training organisation that developed a baseline assessment chosen by 12,000 primary schools in 2016 - has said that it would not bid for the latest version, slating the revised plans as “incoherent, unworkable and ultimately inaccurate, invalid and unusable”.

And Professor Robert Coe, director of the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University, which also ran a previous baseline assessment, has now criticised the latest version.

“Do we need to reform the accountability system? Yes, and radically,” Professor Coe said last month. “Does it make sense to wait seven years from the time children start school to make a punitive judgement about the school, based on the performance of whatever proportion of that small number of children are still at the same school? Not remotely.”

The warnings about the potential baseline pitfalls come after the primary accountability system has looked on the verge of breaking down. New Sats were introduced in 2016 - designed to match the new, more demanding national curriculum - but while teachers were expecting the bar to be raised, they had not expected a shambles.

During Sats week that year, there was a leak of the spelling, punctuation and grammar paper.

The reading test, which left children in tears, was later found by Ofqual to be “unduly hard”.

And the writing assessments, which had to be constantly updated and clarified, brought the unions to the brink of a boycott - only avoided when the government said it would not use the results to intervene in schools.

The writing assessments have now been altered again for this year, to give teachers more flexibility in judging children’s achievements.

But the concerns that the system does not ensure consistency across the country are so great that a recent review of primary accountability by the Association of School and College Leaders argued that if the assessments cannot be better reformed, they should be scrapped entirely.

And this comes on top of the long-standing criticism over the use of externally-marked tests for accountability - that they are only ever a snapshot of a child’s performance on a narrow set of measures on a particular day and that they narrow the curriculum.

Now it looks as if the new baseline assessment, due to start in 2020, will only add to these concerns.

Helen Ward

League tables ‘now too confusing for parents’

One of the key justifications for our school accountability system is that it empowers parental choice by shining a light on school standards.

But while league tables weigh heavily on the minds of teachers and heads, there’s good reason to suspect that their importance is diminishing in the eyes of parents.

Until a few years ago, secondary school league tables were relatively straightforward for parents to understand. Schools were measured on the proportion of pupils achieving a grade C or higher in five GCSE subjects including English and maths.

But all that changed in 2016 when the government moved to its Attainment 8 and Progress 8 metrics.

Ruth Lowe, external affairs manager at Parentkind - formerly known as PTA UK - tells Tes that parents can find performance measures and what they mean “confusing”. Indeed, a Department for Education survey published in January found that less than a third of parents with pupils at secondary school had heard of Progress 8. Part of the problem is that a parent can’t surmise what the measures mean from their name alone. They require a long-winded explanation.

Take Attainment 8, for example: a measure of pupil performance across eight subjects, including maths and English (both “double-weighted”), three qualifications included in the English Baccalaureate (which requires its own explanation) and three other approved qualifications, where the higher the average score the better the pupils at the school are doing. Simple it is not.

Progress 8 is even more complicated because it is a relative measure. As Rachel Atkinson, the Department for Education’s head of inspection and accountability, notes: “It’s a slightly odd measure to understand. It’s a situation where actually if you get ‘0’ you are doing really well.” She admits there’s “quite a job to be done in terms of how we present that and make that understandable”.

The inclusion of EBacc (“very similar to Progress 8” but a “slightly different basket of subjects”, Atkinson observes) complicates the picture even further.

A quick review of how local newspapers reported secondary school league tables in January underlines the confusion.

The Liverpool Echo, for example, chose to highlight Attainment 8 scores to select “the top 10 secondary schools for GCSEs in Liverpool”. The Newcastle Chronicle, meanwhile, focused on Progress 8 to show “the best North East schools by GCSE grade”.

In London, the Evening Standard published a table showing the percentage of students passing five or more GCSEs at A*-C/9-4 (including English and maths), and the percentage passing the EBacc and the Progress 8 score.

So the creation of a plethora of complex performance metrics has weakened the grip of league tables on the parental imagination, but it’s not the only factor at work.

Local newspapers - the traditional medium for disseminating this information - are also in decline. More than 200 have closed since 2005, with about two-thirds of local authority areas no longer served by a daily local newspaper.

Will Hazell

Inspections aren’t 100% reliable, says Ofsted research head

Ofsted’s own head of research has admitted that it is almost impossible to determine conclusively how reliable inspections are.

Daniel Muijs, who was appointed to the role at the start of this year, says: “No system is 100 per cent reliable: that’s never possible. And, always, any inspection involves human judgement.”

Questioned as to whether the inspection system would stand up to research, he points to two studies investigating the reliability of inspections. One, conducted in 1998, “came up pretty positively”, Muijs says. But he adds: “That’s now old evidence.”

A second study, published last year, looked at the reliability of Ofsted’s short inspections. This involved sending two inspectors to visit 24 primary schools, and concluded that short inspections were 92 per cent reliable.

In the past, Robert Coe, education professor and director of the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University, has criticised Ofsted’s inspection process, saying that it was neither research-based nor evidence-based. But he concluded that a finding that 8 per cent of inspections were unreliable was no cause for concern.

“The reality is that this is a subjective judgement process - you’re not going to have 100 per cent agreement,” he told Tes at the time. “The reality is that we’re going to have to live with some misclassification or subjectivity. It’s in the nature of assessment that you get imprecision. There’s no system that anyone could invent, anywhere in the world, that’s going to reduce that to zero. Certainly no feasible or affordable system anyway.”

Nonetheless, Muijs admits that one has to avoid drawing too many conclusions from a single small-scale study.

“Of course, one study has always got its limitations,” he says. “There are many different strands of inspection, many different forms of inspection.

“And there are limitations to how large-scale you can go with those kinds of studies, because, of course, we do not want to overburden schools and constantly be sending multiple inspectors into schools.”

Adi Bloom

How the system is failing ‘inadequate’ schools

When a small primary on the agricultural fringes of a Surrey market town was put in special measures, everyone knew what its fate should have been.

Since a new law was passed in 2016, every maintained school rated “inadequate” has to become an academy, sponsored by a trust given the job of turning it around.

So it must have come as a surprise to the staff and parents of Green Oak CofE Primary in Godalming that, instead of heralding its rebirth, the government’s accountability system has instead led it to the verge of extinction.

It may be an extreme case, but it points to much wider problems with the forced academisation policy that continue to bedevil ministers.

The formal trigger for Green Oak’s plight was pulled in March 2017. The inspectors had found it “inadequate” following a visit in January, and seven days before Ofsted published its report, the DfE issued it with a directive academy order.

But almost a year to the day later, Surrey County Council opened a public consultation on plans to close it at the end of the summer term. The reason? The government said that the school had to become an academy, but no academy trust was willing to take the school on - not even the local diocese’s own academy chain, the Good Shepherd Trust (GST).

The trust’s interim CEO, David Brown, cites its legal obligations to “ensure that any new school does not have a detrimental effect on the services available to the schools and pupils already in its care”.

Because there was no extra money available to help it fix Green Oak’s problems, the GST “took the difficult decision that it could not viably become part of the trust”, he says.

The heavy irony is that the plan to close the school follows an Ofsted monitoring report in November that said the school was “taking effective action towards the removal of special measures”, and praised the work of the local authority.

Green Oak’s situation is rare, but not unique. Surrey County Council has announced plans to close another CofE school, Ripley Primary, for the same reasons. Meanwhile, North Yorkshire County Council is further along the process of shutting Burnt Yates Voluntary-Aided Primary near Harrogate - a small school with falling rolls and financial difficulties - after the diocese failed to find an academy trust to sponsor it despite it receiving a directive academy order in January 2017.

The compulsory academisation of “inadequate” maintained schools was always controversial. But what must concern ministers is that it is an accountability mechanism that is often failing to deliver on its own terms.

Last year, a Tes investigation found that dozens of “inadequate” schools had been left without a sponsor for months on end because no one would take them on. Of 155 schools that had received directive academy orders, 42 were still left without a sponsor one year on.

It is a problem that is not going away. Last month, the National Audit Office found that almost two-thirds (63 per cent) of schools rated “inadequate” in the year up to March 2017 had not become academies within the government’s nine-month target. In the North of England, only one in five had done so. In the dry language of the spending watchdog, “it has taken longer than intended to convert a sizeable proportion of underperforming schools that [the DfE] considers will benefit most from academy status”.

The concerns about the delays extend to Ofsted itself, which told the NAO that it would not normally monitor schools that have been directed to convert, and they would not then have a full inspection for a further two years.

The inspectorate said: “It can be a long time before an independent judgement is made about whether the quality of education has improved in schools directed to become academies”.

The DfE says it is rare that a sponsor cannot be found for a school, and that it works with schools and local authorities to find solutions on a case-by-case.

Martin George

School accountability in other countries

Wales

Until 2000, the testing and tables regime in Wales was the same as in England - children were tested in English, maths and science at ages 7, 11 and 14 ,and individual school results were published in league tables.

But then the principality’s devolved government gradually introduced what many teachers on the other side of Offa’s Dyke would have wistfully regarded as a nirvana of common sense. Wales abolished school league tables in 2001, Sats tests for seven-year-olds were abandoned in 2002 and tests for 11- and 14-year-olds were replaced in 2004 by teacher assessment.

However, things did not turn out as hoped. In 2006, Wales took a full part in the influential Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) rankings of 15-year-olds in maths, reading and science - and did worse than England, Scotland and Northern Ireland in all three subjects.

But it was in 2009, when the next round of Pisa revealed that Wales’ scores had tumbled in all three subjects, leaving it even further behind the rest of the UK, that this system of minimal accountability came under real scrutiny. An influential paper by the Centre for Market and Public Organisation at the University of Bristol said that the removal of league tables was to blame.

Statutory national reading and numeracy tests were reintroduced in 2013 for all pupils in Years 2 to 9.

US

To find the real extremes of education accountability you need to go the US, where naming and shaming has progressed beyond schools to individual teachers.

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times published individual ratings for around 6,000 of the city’s 14,000 primary school teachers, using a value-added measure to show how their pupils’ had progressed.

The newspaper was then boycotted by thousands of teachers after the suicide of Rigoberto Ruelas, 39. His family said had become deeply depressed by his poor rating, after he had been identified in the table as one of the “least effective” maths teachers in the city.

But ranking individuals publicly has not been isolated to one newspaper. In New York, after a long legal battle between unions and the media, the New York City education department released individual performance rankings of 12,000 teachers in February 2012.

The data had been developed for internal use as part of the city’s annual review process, but media called for access. The margin of error on the rankings was wide and so education officials cautioned against drawing conclusions on the data alone.

In 2015-16, New York state educator evaluation data was given as the overall numbers and percentages of teachers rated as ineffective, developing, effective and highly effective - with no personally identifiable information on the website, although parents may contact their child’s district for information about their child’s teacher’s overall rating.

Finland

School inspections in Finland were abolished in the early 1990s and there are no national tests for pupils.

The grades in the basic education certificate, which is given at the end of grade 9 [Year 11] are decided by teachers, and the first national examination does not come until the end of upper secondary education - equivalent to A levels in England.

While there may be no Ofsted-style inspection system or national testing arrangements, there are local boards that evaluate schools, and there are national assessments of a sample of students every year in either mother tongue or maths. These results are used to allow the authorities to follow how students are doing at a national level, rather than ranking schools. School-level results are not published.

Finland’s low accountability model has had much more success in the international league tables than the Welsh one.

But Tim Oates, Cambridge Assessment research director, points out that in the 1970s and 1980s, while standards were rising, the Finnish system did have a highly centralised inspection and testing regime. He argues that in Finland low accountability levels have only worked because the system had initially developed during a period of centralised control.

Helen Ward

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters