How to deploy a hook that engages as well as entertains

Every teacher has a metaphorical toolbox with a variety of approaches to help with engagement. But should hooks be one of them? In some quarters, these attention-grabbing introductions are considered a key element of a lesson or series of lessons. In others, they’re written off as unnecessary razzle-dazzle.

How teachers can use hooks in lessons

Tes spoke to associate research school director Stella Jones about how hooks can help or hinder young people’s learning, particularly when those young people come from a disadvantaged background.

Tes: So, what exactly is a hook?

Stella Jones: Hooks have long been used in primary schools as a way to spark pupils’ interest and enthusiasm for a topic or unit of work. In an ideal world, these would create a captivated and enthused audience who are ready to read and write. But there is a school of thought that hooks are woolly, futile, time-wasting distractions.

In the past, I have seen and used hooks, varying from a simple dinosaur footprint stencilled on to the school playground to the classroom being taped off as a crime scene and a ransom note being frantically delivered by the headteacher.

I have often used hooks simply for the purpose of enthralling, engaging and stimulating, and there really is nothing wrong with that. However, I have now realised the potential hooks have to provide children with essential context, background knowledge or life experiences that many of our disadvantaged pupils just don’t have.

Why is background knowledge so important for literacy?

Good readers bring their own background knowledge and personal prior experiences to any text they encounter.

Both are crucial for understanding and making inferences, as they enable readers to make strong links with their personal values and life experiences, to other texts, genres and authors, and to facts, other disciplines and the real world.

Children with a broad background knowledge are better able to relate to what they are reading (and therefore comprehend it). It also means that they have more detail to hand to enliven and expand their writing.

It is more likely that children from privileged or advantaged families will have the opportunity to collect a diversity of life experiences, from holidays abroad, and museum visits and theatre trips, to various social events.

This cultural capital means that they are exposed to a greater wealth of experiences that expand and extend their oral language structures, general knowledge and vocabulary, and underpin their social and cultural bases. Quite simply, the literacy-rich get richer and the gap between the haves and the have-nots widens.

Activating prior knowledge is a key strategy recommended in both of the Education Endowment Foundation primary literacy guidance reports. If there is a prior knowledge to activate, hooks can help to bridge the gap. We can carefully design a hook that delivers the background knowledge children need to access the task.

What separates an unhelpful hook from a helpful one?

I can give an example from my own teaching. After moving from London to the North East, I made the assumption that a Year 4 class - living within three miles of a seaside town, in an area of high deprivation - would have all been on a trip to the beach.

Our writing that week was a diary entry based around a text we were using, which was set at the beach.

I thought the hook was fabulous: we set up a fake beach in the early years foundation stage area, using their play sand. We had deckchairs, buckets, spades and water.

I started discussions about the sights and sounds we’d expect at the seaside. However, owing to the school’s position on a busy road, these mainly encompassed descriptions based on the traffic noise behind (hardly an authentic experience).

Soon it became apparent, through the further sharing of ideas about the smells and tastes of the seaside, that most children had never actually been. Our lovely hook had provided children with a nice experience but not a meaningful one.

What was the impact on their work, if any?

We continued through the unit of writing but the results lacked depth, richness and crafted description. This was understandable: how could children who had never been to the beach write authentically about a beach-based scene?

This lack of experience also made it trickier to make inferences from our class text. How could they answer questions about spume or the trough of a wave when the students had never been near any? The vocabulary had no meaning for them.

What would a more useful hook look like?

What we did the following year. We ditched the gimmick and our hook was an actual visit to the beach. Armed with this experience, the children were able to tackle the text and writing tasks far more successfully. I learned never to make assumptions and to always gauge carefully where gaps in background knowledge or experiences might be - and use hooks to fill these wherever possible.

So, what should teachers bear in mind when creating their own hooks?

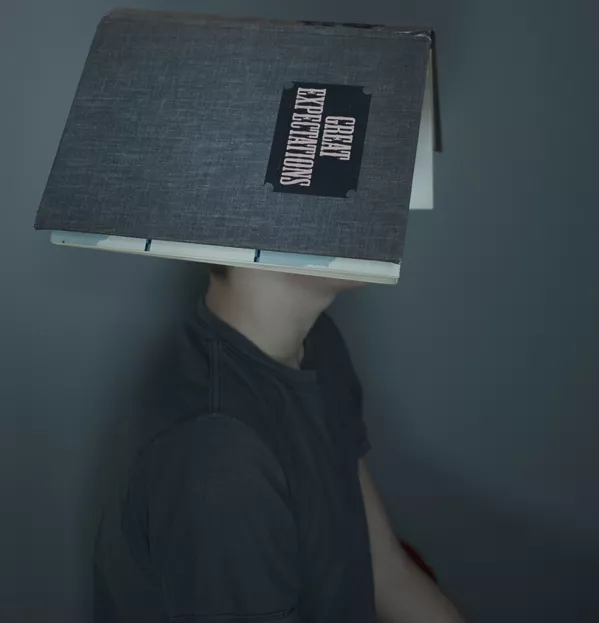

Hooks don’t always have to be so grand. A video, artefact, picture, photograph or book can be used to provide context and give children the background they need.

What we need to do is think carefully about what it is the students need to know first in order to be successful when meeting a text or completing a piece of writing, and then plan the hook accordingly.

Gamifying and dramatising words or events can be useful ways to enable children to explore, understand and attribute meaning to vocabulary and for gaining vital first-hand knowledge about a topic.

If children are to acquire deep and coherent meaning from texts, or bring richness and plausibility to their writing, they must first have the necessary prior knowledge, which will probably need to be explicitly taught.

A hook can help with this but just make sure it’s not an empty gimmick.

Stella Jones is director of an associate research school and leads on teaching and learning across a trust of primary schools in the North East

This article originally appeared in the 12 February 2021 issue under the headline “How I...hook students into my lesson”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters