How a ‘knee-jerk opposition to universities’ was ended

Initial teacher training is in a state of flux. Over the past few years, the system - responsible for channelling some 30,000 recruits a year into schools - has been on a journey away from university-led courses.

But what began as a hell-for-leather dash towards school-led training has slowed to a crawl. As TES revealed last week, university teacher training - not long ago denigrated by ministers as being part of “the blob” - now appears to be back in favour (bit.ly/DfEblob).

Ben Ramm, head of teacher supply at the Department for Education, told a conference in London: “We now have an approach that I would describe as pragmatic rather than focused on any specific structural preference for school-led or university-led ITT.”

The official said education secretary Justine Greening recognised “the importance and value of high-quality university involvement in teacher training” and that this would be “sustained and increased in the coming years”.

So why the switch from abuse to praise? It could be pragmatic - one reason for the proliferation of routes, from Teach First to Troops for Teachers, is that they were intended to suit the distinct needs of would-be teachers. But for thousands of graduates, a postgraduate course at university still appeals the most, so protecting this route makes sense.

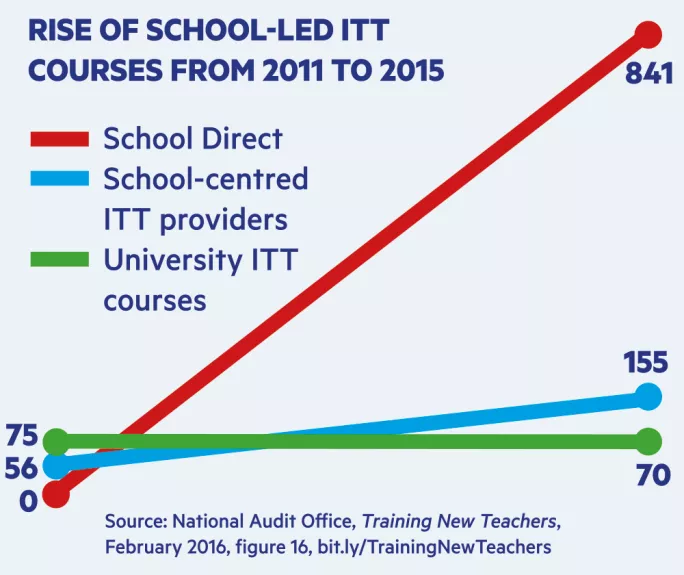

Then there are the logistics: in the five years to 2015, the number of school-centred providers increased from 56 to 155 and the total number of lead schools in School Direct grew from zero to 841. That amount of choice risks confusion for potential trainees. Last year, the Commons Public Accounts Select Committee warned that the proliferation of new routes and growth of school-led training was “reactive and lacks coherence”.

More ‘joined-upness’ needed

But perhaps there is more to the new thinking about higher education’s place in ITT than just pragmatism - universities argue that they are also well placed to tick other policy boxes.

In a speech to secondary heads last Friday, Ms Greening underlined her commitment to a strengthened qualified teacher status and ongoing professional development.

James Noble-Rogers, executive director of the Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers, believes that the university courses he represents could help the minister out with both of these aims.

“I think there is now a recognition of the importance of CPD that implies the need for larger providers and a joined-upness between ITT and CPD,” he said. “Universities are ideally placed to do this.

I have no sense of there being a plan. There is a sense of people having ideas

Mr Noble-Rogers added that reports by Sir Andrew Carter and Stephen Munday for the DfE on ITT content both pointed to the importance of education research and argued that universities were well equipped to provide trainees with research skills.

He does not believe that the DfE is now anti-school-led teacher training, but thinks “they realise things have been spread too thinly”.

“There is no knee-jerk opposition to universities’ involvement in teacher education, which there was in the Gove years,” he said.

Three-year allocations

So the shift in policy appears to have been driven by hard-headed realism about what would most likely attract the necessary graduates into teaching, as well as a need for more coherence in training before and after teachers qualify.

Concerns remain that the government needs to give ITT providers greater stability. For a handful that has already happened, as three-year allocations for trainee numbers were introduced for some providers last year -although the DfE has repeatedly refused to publish their names.

Ms Greening has also said that bids are about to open for separate three-year allocations for “innovative teacher training models” aimed at schools and areas that “need them most”. But no information has been forthcoming about how many providers this could cover.

“I have no sense of there being a plan,” said Jo Palmer-Tweed, executive director at Essex and Thames Primary SCITT. “There is a sense of people having ideas.”

While those in university teacher training might welcome the end of the DfE’s hostility, the sector is still a long way from the stability and clarity of direction it craves.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters