‘I was eating one meal a day’

“One winter it was literally a choice between heating and eating,” says Donna Spicer, a teaching assistant who works in a primary school in Plumstead, south London.

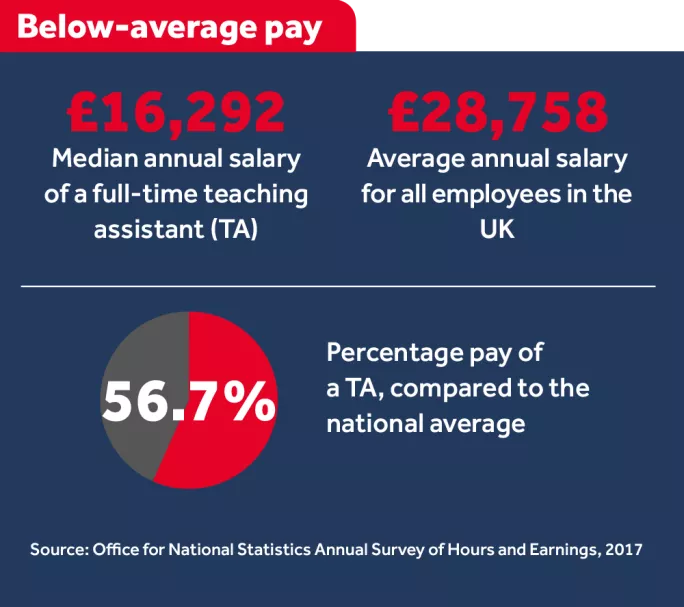

Spicer, a teaching assistant of 18 years standing, is paid a salary of £16,500 and knows how difficult it can be for school support staff to make ends meet on their current wages.

That’s just one of the reasons why support staff are in line for a significant pay rise over the next two years.

The pay offer outlined by the National Joint Council (NJC) - which represents 350 local authorities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland - affects school support staff as well as council workers.

In schools, the reach of the offer will be profound, covering basically all staff bar teachers and senior school leaders.

“It will include everyone from school business managers to cleaners, caterers, teaching assistants, administrative staff, clerical staff - the whole range really,” says Jon Richards, head of education at the Unison union.

The deal outlined by the NJC involves “bottom-loading” - giving those on lower wages a larger pay rise. This is designed to keep pace with a planned increase in the new national living wage, which is supposed to hit 60 per cent of median hourly earnings by 2020 - £8.56 according to the latest forecast from the Office of Budgetary Responsibility.

The NJC offer is designed to create some “headroom” over the living wage, with the lowest paid support staff receiving £9 an hour by April 2019. Bridging the gap between this figure and current wages will require a significant increase - as much as 16 per cent over two years in some cases.

The pay offer is currently being considered by unions, and there is no certainty it will be accepted. The proposal of a 2 per cent annual increase for those on salaries starting at £19,430 is the biggest bone of contention, and the Unite union has already recommended its members reject the offer.

Crippling effect

However, the prospect of a larger increase for those on the lowest wages could not come too soon for struggling school support staff.

Spicer has first-hand experience of the crippling effect of poor pay. “Over half my wages go on my rent,” she says. “By the time I’ve paid out gas, electric, council tax, water, all the essential bills, I’m actually left with £230 for the whole month. Out of that I’ve got to get clothing, food, travel to and from work. It goes nowhere.”

Her teaching assistant colleagues are in the same - or worse - situation. “I know a lady at work, her car broke down, and she was struggling to get into work because she couldn’t afford to fix it,” she says.

Another colleague with young children was forced to go to a food bank. “She was so ashamed,” Spicer recalls.

For her own part, there have been times when Spicer has “gone without”. “There have been times when I was eating one meal a day,” she says. Several winters ago she had to choose between heating her house and putting food on the table. She opted for the latter, making do with blankets and hot water bottles in the evening.

Spicer says she’s particularly felt the pinch in the last year and a half as inflation has increased. “You’re getting less and less each month, because food prices are going up - my wages haven’t gone up by anything.”

It’s not just teaching assistants who are struggling. According to a recent poll by Unison, 43 per cent of school kitchen staff say they are weighed down with debt, other than a mortgage. A quarter of catering staff say they’ve had to take out loans from banks, credit unions or payday loan companies to make ends meet - 21 per cent have had no choice but to borrow money from friends and family.

For Spicer, the most galling thing is that her pay has not grown to reflect how the role of the teaching assistant has changed during her career. “The responsibilities have grown with each year,” she says. “In the past being a teaching assistant would mean sharpening the pencils, washing off the paint brushes, sitting and listening to the children read. That’s progressed to working one to one with not just special needs children, but all children that need support within the classroom.”

Spicer finds herself doing work traditionally done by teachers - producing lesson plans and differentiating work for her students.

“Where I work, we’re classed as non-teaching staff. That’s a real grind to a lot of us because actually we do teach the children.”

Under the NJC deal Spicer is in line for a 5 per cent increase, but the effect of years of poor pay on her and her colleagues has already taken a toll. “It’s hard to watch people struggle for a job that everyone used to really love. We don’t all go into jobs for the money, especially in teaching you do it for the love of the kids. But people are struggling now.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters