‘The impact of teachers being refused visas is now critical’

Kate Johnson had been working as a teacher in a London primary school for nearly two years. She loved her job and was valued by her employer.

As a New Zealander, the time was coming for her to renew her visa - a routine process that required a trip back home.

But one week before her flight, she received shocking news: she didn’t qualify for a visa.

Johnson was so distraught, she had to leave work for the rest of the afternoon. “I had to go home because I was absolutely devastated,” she recalls.

Johnson is now back in New Zealand. The ordeal has taken a huge toll on her, wrenching her away from her British partner and her life in London (see box, right). But it has also left a UK school with one fewer teacher.

Unfortunately, she is not alone. Between December 2017 and April 2018, about 250 applications to sponsor visas for teachers were rejected. Many more teachers are not applying because they have no hope of meeting high salary thresholds.

Tes has heard from multiple overseas teachers who are desperate to work in UK schools but are currently barred from doing so.

And while a recent change of the rules to help overseas doctors could ease the pressure on visas, experts think that teachers will continue to be turned away.

At a time when schools are already grappling with a teacher recruitment crisis, is our immigration system making the situation worse?

In 2011, as part of its commitment to bringing down net migration, the Conservative-led government introduced an annual cap of 20,700 “tier 2” visas for non-EU skilled workers, with places allocated on a monthly basis.

To qualify for these visas when the monthly cap has not been exceeded, applicants require a “certificate of sponsorship” from their prospective employer and generally need to have a job offer with a salary of at least £30,000.

However, when the monthly cap is hit, a points-based system comes into play, which is heavily weighted towards applicants’ salaries.

Up until the end of last year, the cap had only briefly been hit, in one month in 2015. But this year it has been a different story.

Below the salary threshold

In every month since December, the cap has been exceeded, with the number of applications - and the number of rejections - increasing each month.

The system is now so oversubscribed that the salary threshold to qualify for a visa has been sent sky high: in March, applicants had to earn £60,000 to qualify.

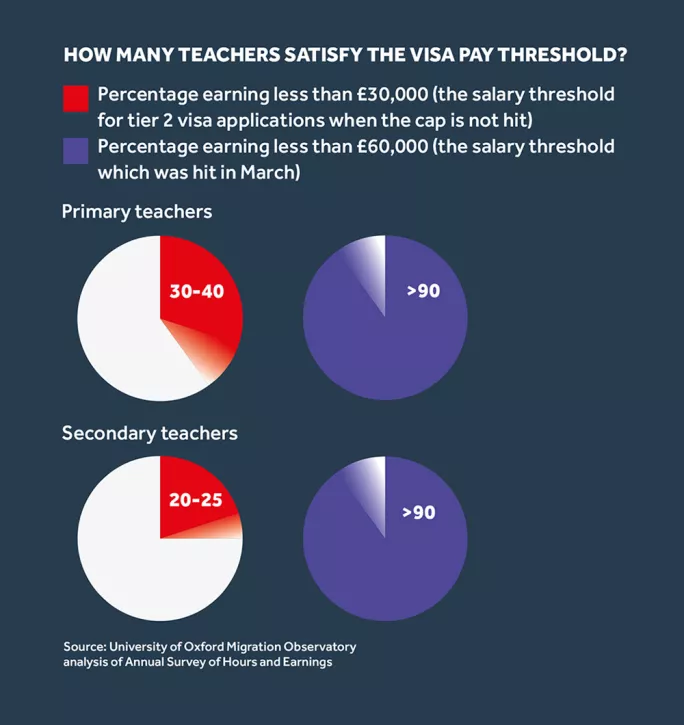

When there is such a high bar, lowerpaid professions - including teaching - suffer the most. According to the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, more than 90 per cent of teachers earn less than £60,000.

A substantial chunk of the profession would not even meet the standard salary threshold in a month when visa applications are below the cap; the Observatory estimates that 30 to 40 per cent of primary school teachers, and 20 to 25 per cent of secondary teachers, earn less than £30,000.

According to data obtained by the law firm Eversheds Sutherland and shared with Tes, between December 2017 and April 2018 there were approximately 300 applications for certificates of sponsorship on behalf of teachers, but more than four-fifths of these were turned down.

Of those applications that were successful, the majority were for teachers in a few subjects designated as shortage occupations - maths, physics, computer science and Mandarin. Shortage occupations get a larger number of points, which means applicants do not need such a big salary.

However, outside these subjects, just three teacher applicants have been successful in five months. With teacher recruitment in dire straits, the visa situation has landed schools with a new problem.

Victoria Eadie is chief executive of Tudor Park Education Trust, which runs three schools in Feltham, West London. Earlier this year, she provisionally appointed two teachers from Australia, having failed to get a field of candidates in this country. The trust had never had difficulty obtaining certificates of sponsorship in the past, but it has been refused visas for both teachers over the past three months.

“Teacher recruitment is such that there physically aren’t enough teachers in the system,” Eadie says. “We’ve got holes for a head of RE and for a geography teacher that we’ve had since January.”

The prospective head of RE was “absolutely perfect” for the role, she explains, but having failed to secure a visa for three months, both parties were forced to decide to give up on the application. “We’ve lost that opportunity, and we still haven’t filled the post,” she adds.

The visa problems are happening at a time when many British teachers are quitting their jobs to teach overseas.

“With recruitment as it is, and our teachers going to teach abroad, the impact of visa refusals is now critical,” says Eadie.

Stumbling blocks

Tudor Park Education Trust is not alone in being unable to recruit international teachers. Esme Dickinson is an HR consultant at law firm Browne Jacobson, but until last month worked for a large multi-academy trust (MAT). Her former employer had never experienced problems recruiting overseas teachers until last year, when it had three visa applications refused.

This causes huge problems for school leaders, Dickinson says. “They’re basing their timetables on having those recruits,” she explains. “You then have to wait for the next monthly cycle for visa decisions, so you’re looking at least a month without that teacher. Then you’ve got the increased supply costs, the impact on teaching and learning. It’s huge for the individual and for the school itself.”

That the visa cap is only now being hit is possibly explained by the fact that it was first introduced in the aftermath of the financial crisis, when the economy and demand for labour were both weak. As the economy has improved, there has been a steady increase in applications for tier 2 visas.

It has also been suggested that the decision to leave the EU has increased demand for non-EU workers because fewer Europeans now wish to come to Britain, though this is difficult to prove.

What is unarguable is the fact that many qualified, overseas teachers cannot take up jobs in UK schools that are unable to recruit at home. But the most pernicious aspect of the current situation is that it is forcing foreign teachers already in the UK to quit their jobs and leave the country.

Many international teachers initially come to work in the UK on a different visa - the “tier 5 Youth mobility visa”. However, this expires after two years, at which point the teacher has to switch to a tier 2 visa if they want to continue working in the country.

In the past, most teachers had no difficulty getting a tier 2 visa if they earned over £30,000. But now the high threshold is forcing people out of work, and leaving classrooms without teachers.

For those teachers who have been unable to get visas, there was a ray of hope last week with the news that the Home Office was going to exempt NHS nurses and doctors from the monthly visa cap. As well as helping hospitals which have been unable to fill vacancies with overseas doctors, this should free up more visas each month for teachers and other professionals.

However, experts think that the cap is likely to still be exceeded and that teachers will continue to be refused visas.

Simon Kenny, an immigration expert from Eversheds Sutherland, says that, based on data from the past five months, exempting nurses and doctors from the cap could free up about 1,150 extra places per month. But he says that schools may “still find it difficult to sponsor most teachers”.

He calculates that the change will bring the required minimum salary down to between £35,000 and £40,000 - still out of the reach of many teachers.

Even at the top end of the main pay range, the majority of teachers would fall shy of this hurdle: those outside of London and its surrounds earn £33,824.

And, even if the number of visa applications falls below the cap, the relief could only be temporary, as there is no guarantee that it will not be hit again.

Schools and other employers cannot be certain what the salary threshold will be, because it has the potential to change month by month.

Uncertainty is a defining feature of the current system, says Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory. “The one thing we know is that it will be unpredictable,” she says. “The UK no longer has a policy on what the threshold is for tier 2 any more - it’s determined by an algorithm.”

When the government announced the exemption of doctors and nurses, it also said it would ask the Migration Advisory Committee to review which professions should be on the shortage occupation list.

The Association of School and College Leaders thinks that there is an opportunity to add all teachers to the list, which would give them a much greater chance of winning visas each month. “We have argued for some time that there is a national shortage of teachers and that teaching should be placed on the shortage occupation list,” says Geoff Barton, the union’s general secretary. Today, Tes is launching a campaign to add all teachers to the shortage occupation list.

“Recruitment from overseas provides a means of overcoming shortages and putting teachers in front of classes,” says Barton. “It makes no sense at all to place bureaucratic blockages in the path of schools, and we will be arguing vigorously for the shortage occupation list to be extended to include teaching in general.”

A fundamental question is whether salary is a fair way of determining priority for visas. “If you use salary for prioritisation then you will have professions like teaching [losing out], where essentially we think their social importance is not reflected in their relatively low salaries,” says Sumption. “That will always create dilemmas.”

A potential solution, she says, is to exempt public sector roles from the cap altogether. Doing this would accord teachers the special status given to doctors and nurses.

Those teachers who are locked out by the current system have a clear view on the fairness of the salary threshold.

“People who work in the public sector in fields like education, they’re never going to make that much money,” says Justine Despins, a Canadian teacher contemplating returning home after failing to obtain a visa. “I’m never going to be able to compete with people in the corporate world for a visa, and I shouldn’t have to - I feel my field is valuable enough.”

Kate Johnson puts it a different way: “The kids are our future, aren’t they?”

“I’m saying ‘our country’ even though I’m not a [UK] native,” she adds. “But our children are our future, and the caps that they are putting on immigration for skilled teachers to be working in the UK are having a huge impact on our future because it’s affecting the progress and the livelihoods of these kids.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters