‘I’ve never had so much stress and worry as this year’

Teachers in England have become used to change in recent years, but for those in secondary schools this summer looks set to be the most tumultuous yet.

The exam reforms set in motion when Michael Gove was education secretary in an attempt to inject more academic rigour into the assessment system have hit their peak, with pupils sitting 20 new GCSEs and 11 new A levels in the coming weeks.

The reforms are being phased in over a four-year period, but 2018 is when they are set to affect the biggest number of pupils and teachers. Teachers have had to deal with a blizzard of changes, including revised specifications, extra content, a completely new grading system at GCSE and linear A levels assessed by terminal exams.

The upheaval has created an “inordinate” amount of stress for pupils, which, in turn, has cranked up the pressure on schools even further, headteachers are warning.

“I have never experienced so much stress and worry as I have this year, and that is among students, staff and parents,” is how one school leader describes the devastating effect on wellbeing caused by the current wave of reform.

But what impact have all the changes had on the quality of learning?

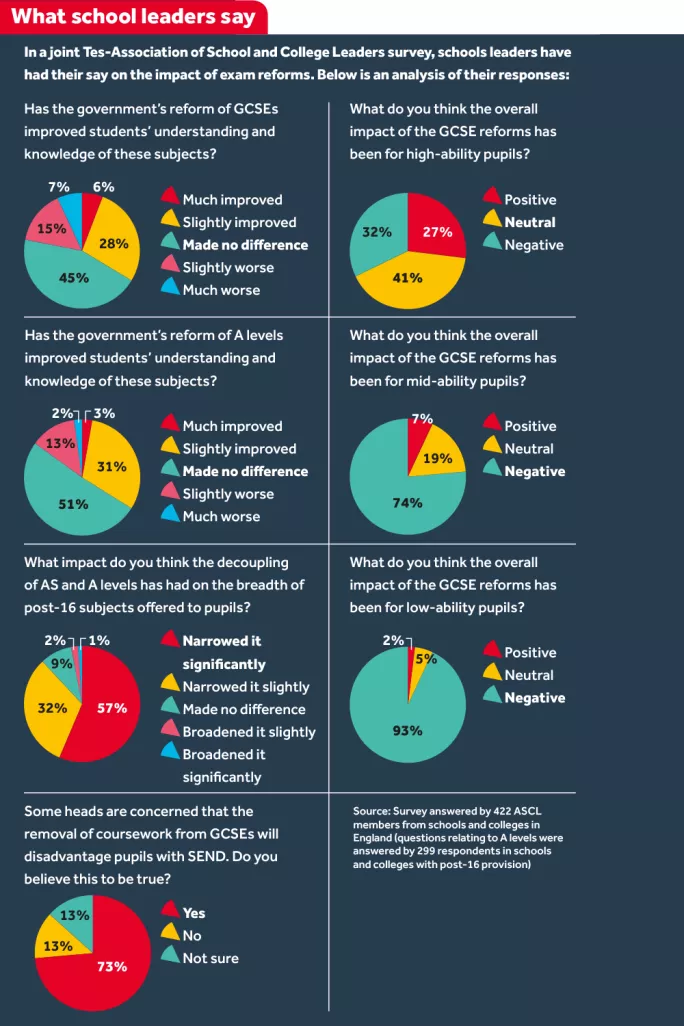

A poll by Tes and the Association of School and College Leaders has found that nearly half of school leaders believe the reforms have “made no difference” to pupils’ understanding and knowledge at GCSE and A level.

Other concerns flagged up by the survey included a narrowing of the post-16 curriculum and a negative impact on pupils with special educational needs and disabilities.

‘Rushed’ exam reforms

Unions and subject associations have also criticised a rushed implementation and a lack of support to cope with the changes.

There is no doubt that these reforms represent the biggest shake-up of the exam system in decades, with the curriculum and structure changed for both GCSEs and A levels.

GCSEs have been reformed to be “tougher”, with a numerical 9 to 1 grade system introduced to allow greater differentiation between pupils. Coursework and modules have largely been swept away for both qualifications.

At A level, students are now assessed at the end of two years - AS levels have been “decoupled” from the qualification, meaning that AS results no longer count towards A-level grades.

The first reformed qualifications, in maths and English, were sat last summer. The number of new exams will peak in 2019, when 25 new GCSEs and 20 new A levels will be taken. But in terms of the number of pupils and teachers affected, 2018 arguably marks the peak of the reform programme - certainly at GCSE level, where big-cohort subjects like science, geography, history and modern foreign languages are getting their first exam outing under the new system. Based on subject entry data from last year, it is likely there will be more than 2.5 million entries for the new GCSEs in 2018, compared with just under 2 million in 2017 and about half a million in 2019.

Suzanne O’Farrell, ASCL’s curriculum and assessment specialist, says that 2018 is a “massive year of reform”. She warns that the education system may have been “lulled into a false sense of security” by the fact that last year’s reformed qualifications were delivered relatively smoothly. There were certainly no ructions similar to the last big shake-up of the exam system - Curriculum 2000 - which contributed to the education secretary at the time, Estelle Morris, losing her job in 2002.

However, while things might have appeared quiet last year, all was not as it seemed. In 2017, revised specifications and a new grading structure at GCSE led to unpredictable results in maths and English. For example, some schools with historically high-performing English departments reported seeing a surprising drop in their results.

The reason this didn’t garner more attention was that Ofqual’s “comparable outcomes” statistical model ensures that, at a national level, students end up with roughly the same spread of grades as in previous years. But at a school and classroom level, results can be much more volatile after such a big shake-up.

One exam industry insider, who asked not to be named, told Tes: “To the nation, it looks like everything has stayed the same, but, underneath, if you look at schools’ performance, they are up and down all over the place.” The insider expects this volatility to continue with this summer’s reformed GCSEs. “A lot of teachers are saying, ‘We just don’t know how our students are going to perform because we’ve never been through a cycle of exams like this.’”

For teachers trying to manage pupil, parent and school leader expectations, this uncertainty can be stressful. Jill Stokoe, education policy adviser at the NEU teaching union, says that making grade predictions has been like “sticking the tail on the donkey”. Teachers “feel really bad” that they are unable to give students an idea of what grade they are on track to achieve, she says. “They feel that their professionalism and their care for their students is diminished by their lack of confidence.”

Unfortunately, this is not the only pressure that teachers have had to contend with. In many of the reformed qualifications being sat for the first time this year, teachers have reported difficulties covering the expanded course content. “The feedback on GCSE has been that teachers are struggling much more to get through - to teach the entirety of the course,” says Alan Kinder, chief executive of the Geographical Association.

“The new GCSE course is too big to teach in two years,” says Stokoe. The NEU says it has heard of schools resorting to a three-, four- or even five-year key stage 4 curriculum to fit in all the GCSE content.

Raising the stakes

Another reason why teachers are feeling the pressure is because the stakes have been raised for their pupils. James Eldon, principal of Manchester Enterprise Academy - a school serving a deprived community in Wythenshawe, Greater Manchester - says that the scrapping of GCSE coursework and modules in favour of an intense six-week exam season takes a toll on pupils. “One of the biggest challenges we face is the ability of the students to sustain and cope,” he says.

Stokoe calls the new linear A level “assessment by ambush”. “It’s one shot and you’re out - obviously that’s very stressful,” she says.

Many school leaders surveyed by Tes and ASCL expressed similar concerns. One said: “Perhaps a reduction in the contribution of coursework was needed in some areas, but the massive increase in content has created a sense of failure among students as they feel swamped, particularly as in many subjects most students will be getting more of the questions wrong.”

Two big bugbears are the breakneck pace of change and a lack of support to adapt to the new exams. Kinder says it is a “big regret” that the government didn’t provide a “comprehensive training package” to help teachers with the new GCSE and A level in geography.

Stokoe says that when teachers are asked what CPD they’ve received to equip them for the new qualifications, their reply is: “Are you kidding? We don’t have any money for that.”

That’s not to say that all of the changes have been poorly received by teachers. “The elimination of the coursework element for a number of GCSEs has made them more straightforward and relieved the burden of managing that element for teachers,” says O’Farrell.

René Koglbauer, chair of trustees at the Association for Language Learning, agrees with that. He says the controlled assessments “caused a lot of administrative nightmares” for MFL teachers. In most subjects, specialists can point to aspects of the new qualifications that they like. Kinder says that geography “did need a refresh of content”, particularly at A level, where the new course contains “exciting themes”.

However, the Tes-ASCL survey suggests that many school leaders do not think that all the disruption has been worth it. Asked whether the government’s reform of GCSEs had improved students’ understanding and knowledge of these subjects, 45 per cent said that it had “made no difference”. Asked the same question about A levels, the figure was 51 per cent. For both qualifications, about a third of those surveyed said the reforms had “much improved” or “slightly improved” pupils’ knowledge and understanding.

The survey flagged up a number of concerns in relation to the reforms. Asked what impact the decoupling of AS and A levels had had on the breadth of post-16 subjects offered to students, 89 per cent of school leaders said it had narrowed it “significantly” or “slightly”. O’Farrell says that this narrowing of the curriculum has been exacerbated by the squeeze on school funding.

“When the decoupling was originally put forward, I don’t think we ever realised the extent to which the funding crisis was going to hit post-16 provision as well,” she says.

The Department for Education says that the new GCSEs and A levels are “the culmination of a programme of curriculum and qualification reform over the last six years to make sure that standards keep pace with the needs and demands of the best employers and universities”.

But there is doubt over whether the new exams are achieving this aim.

One survey respondent said: “There is now far too much content in the new GCSEs to get through in the time available, which means far more didactic/rote learning and less time for more engaging activities and developing crucial key employability skills.”

This was echoed by another ASCL member, who said: “The skills required for GCSE and A level are less about intelligence and application of knowledge, more about memory retention across subjects that have diminishing relevance to the world of work and the future challenges facing young people.”

Another concern is the impact of the reforms on certain groups of pupils. Just under three-quarters of school leaders believe the removal of coursework from GCSEs will disadvantage pupils with SEND.

Vijita Patel, principal of Swiss Cottage School, Development and Research Centre - a special school in London - says that some pupils who would previously have sat GCSEs are now taking alternative qualifications that are felt to be more appropriate to their abilities. The problem, she says, is that these alternative qualifications do not have the same “currency” with employers as GCSEs.

She argues that the way the new GCSE qualification is geared - particularly its focus on pupils engaging with their working memory over the two-year period in which the course is covered - disadvantages some pupils with SEND. “Their actual cognitive ability is on a par with pupils of their own age - it’s that the design of the linear exam is almost putting them 10 steps back,” she says.

O’Farrell believes this is part of a wider issue: the GCSE being redesigned with a particular type of student in mind. “The new grading was designed to bring about differentiation at the higher end and push higher attaining pupils,” she says. She worries that tougher GCSEs assessed via make-or-break exams could hit middle- or lower-ability students.

School leaders share this concern. Asked what the overall impact of the GCSE reforms had been on mid-ability pupils, 74 per cent answered “negative”. A massive 93 per cent said that they believed the reforms had been negative for low-ability pupils.

For the teachers whose pupils are taking new GCSEs this summer, they can at least get some advice from their colleagues in English and maths who were in their shoes last year. And teachers will no doubt show the same phlegmatic, resilient approach that they’ve demonstrated through all the shake-ups of the education system they’ve had to endure over the years.

As Corinne Angier, from the Association of Teachers of Mathematics, says: “Teachers have to be incredibly used to change. You do get more used to things and get on with it really.”

But all this change undoubtedly takes its toll. One school leader, responding to the Tes-ASCL survey, said: “The world moves on, so exams to some degree should be continuously reformed. However, the demands have become too high too soon and placed an inordinate amount of stress on young people and schools.”

Koglbauer believes many of the problems stem from the government’s decision to reform GCSEs and A levels at the same time. He says: “A clear message to policymakers for the future is never, ever to do that again.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters