The Just Say No message isn’t working - but what could?

On a radio phone-in earlier this month, listeners were asked to share memories of the most gobsmacking moments in 80 years of television. There was a predictable mix of responses: the Apollo 11 moon landing, the Queen’s coronation, Michael Buerk’s report on famine in Ethiopia, Emu’s frenzied attack on Michael Parkinson.

But no one mentioned one moment that seared itself into the memories of millions of young people as their oblivious parents prepared tea one afternoon in 1986. In this broadcast, Zammo, the classroom scamp of school-based children’s drama Grange Hill, was unrecognisable: he had become a heroin addict, and we watched aghast as he slumped next to a toilet bowl, clutching a needle and wrap of foil.

‘Shock and horror are ineffective in terms of prevention’

The Just Say No single spawned by the storyline echoed the drugs education taking place in schools in the 1980s, which was little more than a litany of dire warnings. Thirtysomethings may recall a policeman visiting their school and sonorously spelling out in detail the dangers of illicit substances, many of which they had never heard of.

Education on drugs, alcohol and smoking is still, to this day, often reduced to a rushed hour or two of grave warnings in PSHE (personal social, and health education), according to charities that deal with substance abuse. And going by the findings of new national research, whatever Zammo-like pitfalls teachers depict, this appears to have little impact. As David Liddell, director of the Scottish Drugs Forum, told TESS: “Shock and horror are ineffective in terms of prevention.”

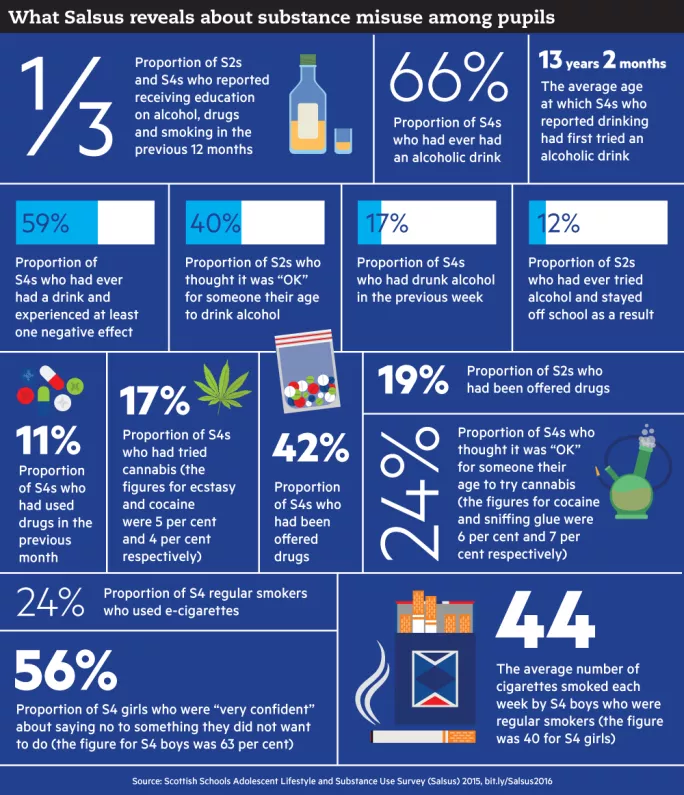

A series of new reports from the Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (Salsus) - looking at S2 and S4 pupils’ experience and knowledge of alcohol, drugs and tobacco - includes one particularly sobering observation about schools’ contribution: “Overall, receiving lessons on a substance was not correlated with lower levels of use.”

Information and influence

Yet Salsus also notes that substance misuse among 13- and 15-year-olds has been falling for two decades, amid wider social and policy changes. Which begs an obvious question: if it makes little difference, is there any point in schools providing education about drink, drugs and tobacco?

Expert charities, while critical of the variable standard of education in schools, believe it can make a difference, but say it must change. Liddell argues that existing school education on drugs does influence pupils - but mostly those who are less likely to succumb to using them anyway.

Salsus, he adds, suggests that these pupils receive “enough information to articulate a reason not to use”.

However, the message from schools “is not getting across to the pupils about whom we should be most concerned”, Liddell explains. And, in any case, schools “reflect a wider societal confusion”.

Why, for example, are young people routinely told about moderate drinking, Liddell asks, or how to put someone who is drunk and unconscious into the recovery position, but no such pragmatic advice is offered about reducing the harm of drug use?

Sheila Duffy, chief executive of anti-smoking charity ASH Scotland, says trying to instil fear and a sense of the forbidden is not a good starting point. Instead, she argues, schools should send out positive messages about health.

She favours a whole-school approach rather than it “just being left to [PSHE]”. That might encompass history (the changing tactics of tobacco advertising), religious, moral and philosophical studies (the ethics of tobacco companies targeting the developing world) and maths (the long-term price of cigarettes).

But everyone in the school community has to buy into this: when smoking is banned on school grounds, for example, it sends out mixed messages if teachers, catering staff or visitors are seen lighting a cigarette.

Trying to instil fear and a sense of the forbidden is not a good starting point

While school education is “probably not all that effective in changing behaviour” and suffers from inconsistent approaches, Duffy says powerful results can be achieved when teachers work with health officials over a long period - and hand responsibility to pupils.

The Assist (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial) programme, developed by Cardiff University, was taken on by the Scottish government for three health boards in 2014. It relies on taking S1-2 “peer influencers” out of the classroom for training, before sending them back to have informal conversations with classmates about the risks of smoking. If it was implemented throughout the UK, Duffy argues, it could prevent or delay 20,000 young people starting smoking each year.

Alison Douglas, chief executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland, similarly says that one-off sessions in schools about the dangers of drink are “unlikely to have any lasting benefits”. She also warns schools to be wary of substandard materials and programmes that have not been independently evaluated, or might even have been created by the alcohol industry.

Alcohol education can help pupils to “make more informed choices”, Douglas says, but “on its own, it is unlikely to change behaviour”. The ubiquity of alcohol advertising and the ease with which pupils can get hold of drink “are the issues we need to focus on to better protect children and young people from alcohol harm”, she adds.

Euan Duncan, a guidance teacher and president of the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association (SSTA), is surprised that many pupils in Salsus reported not receiving recent education on drugs, alcohol and smoking. Pupils may be so disengaged by teachers’ methods that they “switch off”, he suggests.

He believes that school approaches have probably not changed much in decades, despite the fact that there is now a much better range of outside speakers - such as medics and reformed addicts - willing to visit schools and deliver memorable lessons. Even some of the best resources, he adds, may not have been updated since the early 1990s.

‘Maximise support’

Susan Quinn, the EIS teaching union’s education convener, agrees with the Salsus position that the more engaged a pupil is with school generally, the less likely they are to misuse substances.

She adds that pupils who have poor health, a disability or mental health problems, or those who are carers, may be more susceptible.

‘Pupils’ sense of hopelessness and isolation must be minimised’

“Schools need support from health and other professionals in order to maximise the support that they can provide for young people facing such challenges,” says Quinn, citing support assistants, educational psychologists, mental health specialists and home-school link workers. If that “sense of hopelessness and isolation is minimised”, she adds, then “so is the incidence of substance misuse”.

The likes of Liddell sympathise with teachers, believing that “we probably expect too much of schools on issues like drugs”. But no one TESS spoke to from the schools sector wanted to shirk responsibility on alcohol, drugs and smoking education, whatever extra demands this placed on an already stretched profession.

Jim Thewliss, general secretary of School Leaders Scotland, sums up this view by depicting school as a last-chance saloon for pupils who are not getting the right messages elsewhere. “For a great many things, schools will compensate for the deficit at home - and that’s why substance misuse is dealt with in the classroom,” he says.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters