Knowledge is not enough

I gave a speech at the recent Bryanston Education Summit asking the question: what should schools teach - knowledge or skills?

My conclusion was clear. Schools should teach knowledge and develop pupils’ skills. Knowledge acquisition and skills development should be planned for and assessed. Knowledge and skills are, indeed, interdependent. Skills need a context in which they can be fostered and developed. In schools, this context is the curriculum, built, in English schools, upon a subject knowledge base.

Just writing this will, I realise, provoke the wrath of some who ardently believe that there are no such things as skills and that, even if there are, it is not the job of schools to develop them. Teach a powerful knowledge curriculum, they argue, and give pupils the cultural capital to compete in the real world.

To them, I reply that knowledge is essential, but it is not enough. Our school leavers also need skills, which should be fostered, nurtured and evaluated in our education system.

If skills are ignored, some pupils - those usually with advantaged backgrounds - will develop them outside school anyway. But those who don’t have such advantages run the risk of leaving school without the social, emotional and personal skills they will need for a successful adult life.

Andreas Schleicher, head of the education division of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the brains behind its Programme for International Student Assessment education league tables, is a strong advocate of knowledge and skills.

He argues that we now educate children and young people in a world that is changing faster and more furiously than ever before, and that schools, in his words, “need to prepare students more and more for rapid changes - to train for jobs that have not yet been created…to use technologies that have not yet been invented.”

Schleicher points out that our world is becoming ever more interconnected. The easier it is for us to communicate with others across the world, the more our school students need to understand and appreciate different perspectives and world views.

In arguing for skills, Schleicher is emphatically not downgrading the importance of subject-based knowledge disciplines. He writes: “Of course, knowledge will always remain important. Innovative or creative people generally have specialised skills in a specific field of knowledge or practice. As much as learning to learn skills is important, we always learn by learning something.”

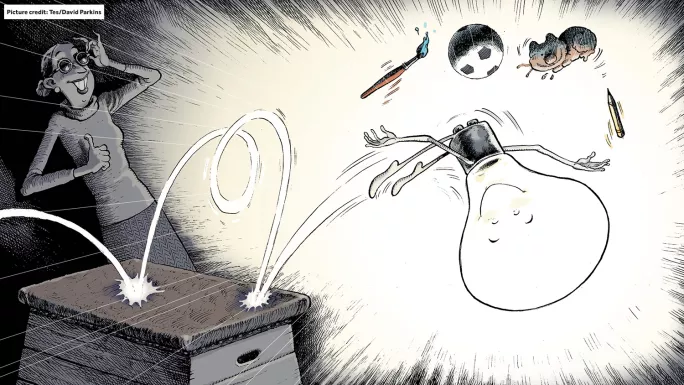

In his excellent book The Missing Piece: the essential skills that education forgot, Tom Ravenscroft attempts to define knowledge and skills. Knowledge, he argues, is the ability to recall, understand and explain. Skills are, by contrast, the ability to do something - to successfully enact a repeatable process. And skills are primarily taught through a combination of “modelling, theory, application, reflection and continued practice”.

So, what might these skills be? Let’s consider, first, the personal skills that our pupils will need. Ravenscroft gives us a good starter for 10 when he writes: “Such skills are involved in achieving goals, living and working with others and managing emotions. They include character qualities such as perseverance, empathy or perspective, mindfulness, ethics, courage and leadership.”

Ravenscroft notes that developing these characteristics is often what distinguishes elite schools. But, he cautions, for the majority of students, “character formation in schools remains a matter of luck, depending on whether this is a priority for their teachers, since very few education systems have made such broader goals an integral part of their curriculum”.

This is certainly the case in England where the schools’ minister, Nick Gibb, is said to be allergic to the term “skills” and to have banned it from Department for Education documents.

The only way is upskilling

But even in this harsh climate, organisations are successfully working with schools to develop pupils’ skills. Enabling Enterprise is an organisation that has worked with more than 500 schools to develop a “skills-builder toolkit” for teachers and school leaders to use to identify and build pupils’ abilities in eight key areas: listening, presenting, problem-solving, creativity, staying positive, aiming high, teamwork and leadership.

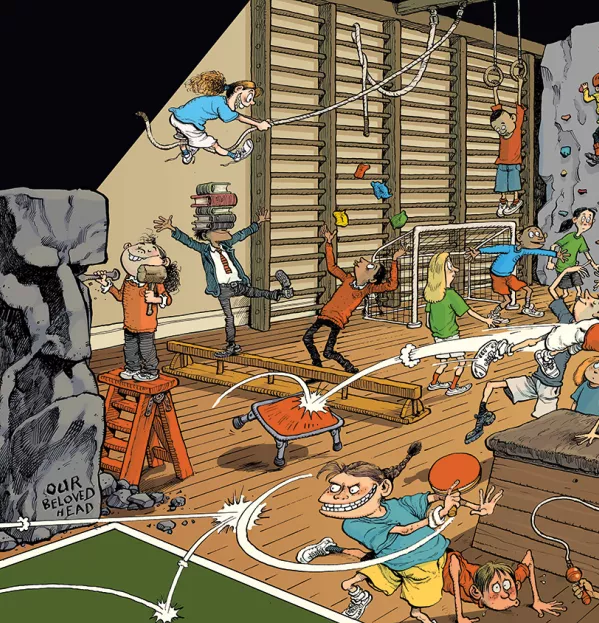

This is a very useful framework for thinking about skills. Added to it should be the motor and fine-motor skills that all our pupils need to develop. The craft skills of making and doing in subjects that develop the skills of physical coordination and creativity - design and technology, music, art, drama and, of course, digital skills.

Nor should we neglect the physical skills and habits needed to address the obesity epidemic among the young, which will be the biggest threat to their physical wellbeing in later life.

But pupils in England’s schools are facing a narrowing of the school curriculum. A toxic combination of inadequate funding and the English Baccalaureate accountability measure is forcing school leaders to cut arts subjects - music, art, dance, drama, and design and technology - from the curriculum.

In the current environment, a focus on skills development in schools is, too often, buried under the weight of subject knowledge content required by the new GCSEs. And as English schools are heading down this path, we learn that other high-performing education nations are deciding to take quite a different direction: countries such as Singapore, which has acknowledged that decades of didactic teaching towards high-stakes exams has resulted in high levels of student stress and unhappiness.

Singapore also acknowledges that its education system has produced students who are compliant, with high levels of academic achievement, but who leave schools without the essential skills they need in their adult lives. We have not, said the city state’s minister for education recently, created good communicators, rule breakers, inventors and entrepreneurs.

So, in Singapore, there is a new education goal - to develop the whole person and to promote the personal attributes of self-awareness, self-management, self-assessment and responsible decision-making.

And Singapore is not alone in refocusing the goals of its education system beyond narrow academic curricula and high-stakes testing. New Zealand, Japan, Estonia, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Ontario are also pursuing similar approaches.

Recipe for success

These nations realise that there has to be another way. The OECD realises this, too. As Schleicher argues: “If everyone can search for information on the internet, the rewards now come from what people can do with that knowledge.”

Applied knowledge, interdisciplinary knowledge, skills development: this is where successful education systems are heading. Systems which recognise that employers increasingly need learners who adapt easily, and are able to apply and transfer their skills and knowledge to new contexts. Where does this leave us in the UK? Well, we are top of the memorisation table, coming behind only Uruguay and Ireland for rote learning which - as the OECD international evidence base proves - is fine for simple, basic knowledge but becomes less effective as a teaching strategy the more complex and high level the learning needs to be.

Teachers in the UK don’t want to teach this way. In its international survey on teacher beliefs, the OECD reports that UK teachers believe their role is to enable their pupils to be ingenious - to think of solutions to practical problems themselves and to promote their students’ thinking and reasoning processes.

Successful education systems take skills development seriously. They do not leave it to chance. And in doing so, they help to prepare pupils for their adult lives.

Employers are very clear that, by the time they leave school, young people must be highly skilled in communicating and working with colleagues.

Sir Mike Rake, former chair of the UK Commission on Employability and Skills, argues that employability skills are the “lubricant of our increasingly complex and interconnected workplace”. He, too, is clear that knowledge and skills are not interchangeable. Both are needed. But skills “make the difference between being good at a subject and being good at a job”.

School is not an end in itself. It is an important stage in children’s and young people’s journeys towards adulthood and independence. They need knowledge and they need skills - schools should build both.

Mary Bousted is joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union. She tweets @MaryBoustedNEU

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters