The last outpost

“Let me give you a fact about this town,” my taxi driver said. “There are more people here with chunks bitten out of their noses than there are anywhere else in the British Isles.”

I had been invited to spend five days in a school in one of the most deprived estates in one of the most deprived towns in England. As I walked through its corridors for the first time, I looked for any clues: peeling paint, the sounds of misbehaviour, mutilated noses.

In fact, the school was bright, clean and quiet, its staff almost unnaturally cheery for a Monday morning.

I realised then that I had no idea what to expect: no idea what a working week meant for the teachers and support staff I was about to meet. I certainly had no idea how eye-opening, chastening and just plain exhausting the next five days would be.

Monday

The children were not beaten over the weekend. This is what Lucy Turner establishes on Monday morning.

A phone message has been left at the school by the police, saying that there has been a domestic-violence incident related to one or more pupils at Pinder Street Primary.

Turner, the school’s assistant head, makes the call to the police.

It transpires that, in the early hours of Sunday morning, the drunken father of two Pinder Street children broke into the home the boys share with their mother. He attacked the boys’ mother, before police arrived and he was arrested.

Neither of the boys was harmed, although it is not clear whether they were awake during the attack. Turner puts down the phone, sighs and runs her hands through her hair.

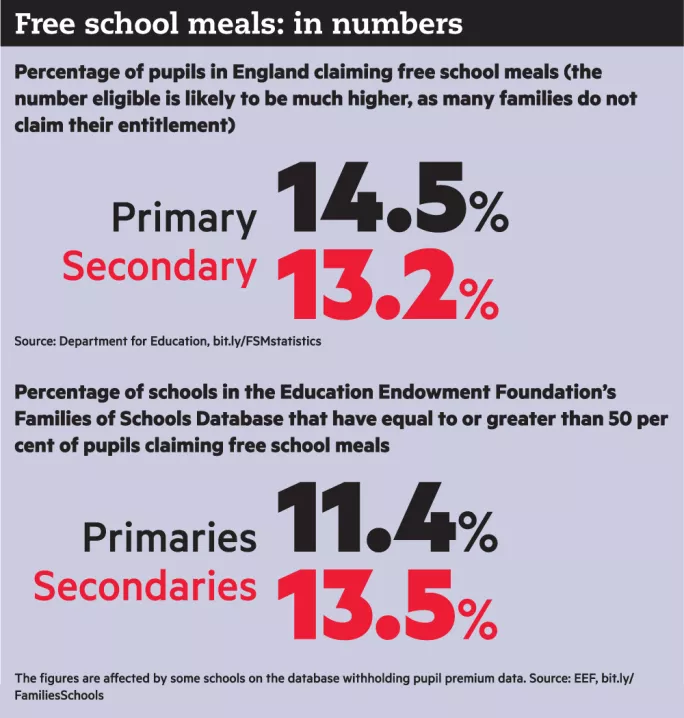

This is not an unusual start to the week at Pinder Street Primary. Situated on a council estate in a coastal former industrial town in the North of England, the school serves one of the most deprived catchment areas in the country: 76 per cent of pupils receive free school meals; similar numbers attract pupil premium funding.

Outside, although it is still only September, the wind is beginning to bite. Mothers brush strands of hair from their faces as they drop off their children at the school doors. Claire Mitchell, Pinder Street inclusion manager, stands huddled in a parka.

“Morning, Jessica,” she says to a little girl being led into school by her father. “Looking beautiful.”

Her father rolls his eyes. “She’s been a pain all weekend.”

Another father approaches. “Morning, Mr Bulmer,” Mitchell says. “How’s Riley?”

The two of them have a brief chat, after which the father leaves.

“He’ll be in touch again,” says Mitchell. “I’m working with him and his wife, trying to get them to do things on their own.

“It’s just parenting stuff: behaviour management, usually. Or confirmation - we work with them to do something and, when they manage to do it, they want confirmation that they’ve done it right. Like if they’ve managed to get Riley sleeping in bed, because usually he sleeps on the couch.”

Pinder Street serves a community where grandparents and grandchildren live on the same street. People rarely move out of the area; for most, their world stretches no further than the route of the number 8 bus.

In an effort to change this, each of the teachers has pinned up a graduation photograph of themselves - complete with gown - on their classroom door.

“We did this to see who went the furthest away for university,” says head of school Helena Neville. “We tell the children, ‘If you want to aspire in life, you’ve got to leave and then come back.’ ”

She opens the door of the Year 3 classroom. “That boy over there?” she says, indicating a child with red hair and glasses. “His mum’s an alcoholic. His dad’s about 70.”

A little girl with a hearing aid walks past. “We have about nine hearing-impaired children,” Neville says. “That’s down to foetal-alcohol syndrome.”

She walks through into the Year 6 classroom. “Are you tired, Debbie?” she says, stopping a girl with sandy-brown hair.

The girl has visible bags under her eyes; she nods slowly.

“Debbie’s looked after by her nana,” Neville says later. “So much rejection in her life: mum and dad and aunty, because they couldn’t cope.”

She shakes her head.

“She can be quite challenging but, you know, if she was brought up in a nice, stable home, she’d be happy as Larry.”

As Neville leaves Debbie’s classroom, she walks past the school inclusion office. This is where Mitchell is based; it is where pupils come - or are sent - when they need some time away from the classroom, or when they have been acting out.

She knocks on Mitchell’s door, and looks round. “Any news of little Riley Bulmer?” she asks Mitchell.

“Nothing,” says Mitchell.

Neville looks surprised. “Is he not in?”

“No,” Mitchell’s voice rises in pitch, “he’s in!”

Last week, seven-year-old Riley was sent to her office every single day. The fact that there has been no sign of him all morning is therefore cause for celebration - and for reward. Picking up her selection of brightly coloured stickers, Mitchell walks to Riley’s Year 3 classroom.

Riley is not there. Neither are his classmates: they have all gone swimming this afternoon. Mitchell returns to her office.

Five minutes later, however, assistant head Turner is at the inclusion-office door. “It’s Riley Bulmer,” she says. She sounds slightly breathless. “He’s refusing to come back to school.”

She glances at Mitchell; Mitchell glances back.

“I’ll go,” Turner says, and runs across the hall and out to the car park.

Mitchell sighs and puts the stickers back in their box.

Tuesday

It is 8.25am. Mitchell is having coffee in the inclusion room when there is a knock on the door. It is Riley’s class teacher. Immediately, Mitchell gives her a hug.

The teacher flops down on one of the chairs. “I have no words. I was walking along the corridor, dragging my swimming stuff behind me, my hair all frazzled, and I was just…” She holds up her hands. “I have no words.”

Riley began misbehaving during the swimming lesson, she says. Afterwards, he started kicking and hitting the other children in the changing room. He was taken to change on his own, at which point, he refused to board the bus back to school.

Riley is in the midst of the process of being assessed by child and adolescent mental health services. But, until he is given a diagnosis, any extra support must be funded by the school.

This is a situation that the school finds itself in again and again: a choice between providing the best possible service for children and spending money that it simply does not have.

“The money we get from the government and the local authority is never enough for what we’ve got in place,” says Neville.

Mitchell’s role is covered by government funding, for example. But the job is too large for one person, so the school pays an inclusion assistant as well. Similarly, a play therapist comes in once a week. But the school is in the process of engaging a second therapist, to cover the need.

“We have to decide where our priorities lie,” Neville says.

It is almost lunchtime now. Outside Mitchell’s office, a group of children has gathered. Turner, on her own lunch break, comes to join them. Today, she is on red-card duty. All children who misbehave are awarded a red card, which equates to a supervised, silent lunchtime.

And so, once all five children are present, Turner leads them down to the dining hall. They all - Turner included - queue up to receive their meals.

“Ms Turner,” one of the five, a girl with dusty blonde hair, says as soon as she is seated.

“I am interested in what you have to say, Jamie-Lee,” Turner replies. “But not today, because you’re on a red card. So you have to be quiet.”

This is a deliberate approach, she says, “because we’ve got to maintain their self-esteem, but they still have to know that what they’ve done is wrong”.

The school must make a choice between providing the best for children and spending money it simply does not have

She glances at the pupils opposite. “Kalen, knife and fork. Jamie-Lee, knife and fork.”

A boy spears his broccoli with his fork. “Where’s your knife, my love?”

“I’ve used it,” he says.

“But I’d like to see you use it all the time, Kalen. I taught you, Jamie-Lee, do you remember?”

Across the table, Jamie-Lee breaks away from effortfully carving at a piece of cucumber in order to nod assent.

In the remaining minutes of her lunch hour, Turner calls up the parents of the red-carded children.

“You may want to talk to him about that when he gets home today,” she says to one of them.

To another: “But he’s shown remorse, so I think we all need to move on.”

Mitchell, meanwhile, is packing her bag: she has a meeting to discuss the domestic-violence case that was reported the day before. Together with the boys’ mother, the school, the police and social services will arrange a protection plan for the children. This will be statutory, and reviewed at regular intervals.

She is just about to leave when Riley’s teacher knocks at the door. “Can we borrow a phone to call Riley’s mum?” she says.

Mitchell feigns surprise. “Is it for being silly? Is it for being naughty?”

The teacher shifts out the way, and a small boy squeezes past. He is seven years old; he has large eyes and a keen expression. “It’s for being good!” he says, with an expression of evident triumph.

“Oh, Riley,” says Mitchell. “Look at my face. Look at how happy I am. But you’ve let me into a secret now: I know you can be good. So what are you going to have to do?”

“Be good,” Riley says.

“Every single day, for the rest of your life.”

Mitchell passes the phone to the teacher, who dials the number for Riley’s father. “Mr Bulmer? It’s Riley’s teacher from school. I’m ringing with fabulous news. He’s been outstanding this morning. Oh, I’m not just smiling, Mr Bulmer. I’m doing backflips.”

She passes the phone to Riley. “Hello, Daddy? I’ve got three stickers. I have to go now, but I’ll be good for the rest of the day.”

Wednesday

“Jamie-Lee’s been acting up,” Neville says to Mitchell.

Last night, there was a fight on the estate between a group of Year 6 girls. Complaints - and requests for intervention - have since reached the school.

Jamie-Lee was born addicted to heroin. Her mother was 15 years old at the time; since then, her mother has been in and out of prison, as a result of efforts to feed her drug habit. Two years ago, Jamie-Lee’s mother was rushed to hospital: she had been injecting drugs, and the site had become infected. The infection had spread to her internal organs, and a large section of her side had to be removed. For a while, Jamie-Lee was uncertain whether her mother would live or die.

Now, Mitchell decides to hold a friendship circle for the Year 6 girls. Around 10 of them trail in and take up seats in the inclusion room. Jamie-Lee sits apart from the others; she slumps low in her chair.

“I’m worried about how the behaviour has changed among some of the most clever, responsible, sensible girls in our school,” Mitchell says. “My concern is that that’s disrupting not only your class time and your friendship time but also now the community. I mean things that are causing distress or anxiety when you’re out of school.”

Most of the girls have lowered their eyes. Jamie-Lee, however, fidgets in her seat.

Jamie-Lee was born addicted to heroin. Her mother was 15 years old at the time

The group of girls is going to meet every week, to discuss these problems, Mitchell tells them.

“So, first of all, who would like to think of a name for this group?” They settle on Girls Aloud; their motto is #JustSaid. Then they draw up a list of rules: honesty, courage, happiness, friendship, respect (“R-E-S-P-E-C-T, find out what it means to me,” Mitchell sings; the girls laugh and ask her to sing it again).

Then Mitchell tells them that she is going to read them a story. The book is a morality tale about a creature who is so worried about being hurt by other people that he hurts them pre-emptively. Eventually, no one wants to know him; all brightness and colour drain from his life.

At the end, most of the girls have given real thought to the issues raised. Jamie-Lee, however, squirms in her seat some more.

“I don’t like stories,” she says. “Stories are for babies.”

“And she’s the one we need to reach,” Mitchell says later. She has already spoken to the play therapist about Jamie-Lee; now, she hopes to arrange sessions for her as soon as possible.

Once the girls have all filed back to their classrooms, Mitchell packs her bag. She has a home visit to pay, to a toddler who is about to start the school’s pre-nursery class. The toddler’s family is already well-known to staff at Pinder Street. Her mother was excluded on a number of occasions. Her uncle achieved local infamy when, at the age of 12, he was arrested for joyriding. At 18, he was caught dealing drugs; he is now in prison.

The partner of the toddler’s mother recently attacked the child; as a result, the toddler is now living with her grandmother.

Shutting the inclusion-room door behind her, Mitchell heads out.

Thursday

It is 11.30am. Every morning, Mitchell calls up the parents of children who are absent from school without authorisation; today, she has not been able to reach them all. So she is paying home visits.

There is no answer from the first two houses. At the third, however, there is a muffled call from within. Then a man in a tartan dressing-gown opens the door.

“I’m sorry,” Mitchell says. “Did we wake you?”

The man yawns and blinks. “I’m sorry. We’ve got our days mixed up.”

“Is Lily-Rose upstairs?”

The man blinks again. “I’m not sure.”

He disappears upstairs to check; Mitchell cranes around the front door for a glimpse of the living room. She is concerned about the man’s appearance, she says. It is not the dressing gown that worries her: it is the fatigue. He may have taken sleeping pills; Lily-Rose’s mother has a history of amphetamine use.

A voice calls out - “Yes, she is!” - before a nine-year-old girl, still dressed in her pyjamas, comes down the stairs.

Mitchell keeps smiling. “I can take Lily-Rose into school, if she gets dressed.”

Lily-Rose runs back upstairs. Moments later, she reappears in a summer blouse and coat. “Am I late for swimming?” she says.

“No, no,” Mitchell says. “Have you had anything to eat today?” Lily-Rose says that her stepfather gave her some Cheerios.

“So why didn’t you come into school, if you were up?”

“I thought it was the wrong day. I thought it was Saturday.”

Mitchell has been buckling her seatbelt; now, she twists round to face Lily-Rose. “Really? Well, I’m afraid it’s only Thursday.”

Later, as school ends, staff gather in the hall for a CPD session on internet safety. Here, an unexpectedly animated man discusses porn and sexual grooming.

Then he moves on to fundamentalism. “You might think Isis won’t come to your town,” he says. There are nods from the staff: Pinder Street has two Chinese children, one Hindu and one Muslim. The rest of the 500 pupils are white. “But what about these people?”

He clicks on the next slide, and a picture of the English Defence League logo fills the screen. Not far from Pinder Street, a recent council by-election voted in a Ukip councillor with an overwhelming majority.

“’If we get the foreigners out, then we’ll have our jobs back’,” the speaker says. “It’s a very persuasive argument for people who have nowt.”

Friday

Year 5 teacher Jo Humphreys is conducting a circle-time session on anger management.

“Anger is like feeling happy or feeling upset,” she says. “It’s a human feeling.”

One girl puts up her hand. “You might hurt yourself,” she says.

“What do you mean by that?” asks Humphreys of the girl.

“You might get that angry at yourself that you want to hurt yourself.”

Humphreys then tells the class the story of Marvin and Christina, who are both angry.

“Do you think they can talk while they’re angry?” she says. “What should they do?”

Hands go up around the circle. “Walk away until you’re calm?” one girl says.

“Very good. What else can you do?”

“Say sorry.”

“Hmm.” Humphreys says. “If you’re feeling really, really angry, do you think ‘sorry’ is something that will come out of your mouth easily?”

While she and her pupils move on to play an anger-management version of snakes and ladders, Year 6 pupil Kalen is standing at Neville’s office door, holding a cold-pack to his knuckles.

“Kalen! What happened?” Neville says.

Kalen looks at his feet. “I punched the door.”

“My goodness,” says Neville. “What has the door done to you?”

‘Kalen! What happened?’ Kalen looks at his feet. ‘I punched the door.’

Kalen’s mother does not want him. She cannot cope, she says; she has called up the police and social services, asking them to take him off her hands. The school arranged a meeting between Kalen’s mother and social services for the following Monday, but the social worker has just called to say that no one from her office will be able to attend.

“They say Kalen’s mother won’t answer the phone,” Neville explains. “But she answers every time for us, because we keep trying. And if we can’t get through, we’ll go round to the house.

“What does it say to a family if mum’s saying she can’t cope and social services are saying they can’t turn up for the meeting?”

Because of his earlier behaviour, Kalen is being kept in detention after school. The misbehaviour itself did not necessarily merit detention, but Neville did not want the threat of a red card hanging over Kalen’s weekend. “The hardest thing about Fridays is that you want them to have a new start next week,” she says.

Kalen, however, does not show up for his detention. Neville informs Mitchell of this, and Mitchell goes back to her office to call Kalen’s mother. Returning, she tells Neville that his mother has promised to send Kalen back.

Neville looks at the clock. It is 3.40pm. “I’m leaving at four on the dot,” she says. “I don’t know why she thinks it’s worth sending him back now.”

She sends the final emails of the day, and then starts tidying her desk. She is just logging off her computer when there is a knock at the door. Sheepishly, Kalen steps into the office. It is five to four.

“Seriously?” says Neville.

“I forgot,” Kalen says.

Neville sighs. “I’ll give you a piece of paper and, if I see you trying very hard, then maybe I’ll let you off detention on Monday. All right?”

Kalen nods. He takes the paper and sits down in the office to work. Neville turns her computer on again.

Reflections on the week

When you spend only a week somewhere, your view is coloured by the fact that you are going to walk away. It can’t be otherwise.

For a week, I cared about the children I met, but I also knew that I wasn’t required to care about them any longer than that.

I could go back to the TES offices and talk about how exhausting - mentally and physically - life in the school was. I could mutter platitudes about how delightful the children were (and they were, often minutes before an outbreak of temper or violence), how bright they were, how much potential they showed, if only something could be done about it.

Every day, the staff give those children their all, in the hope that it will be enough

And, the entire time, I could rest in the journalist’s safe place, where no one would ever require me to do anything about it.

The teachers and support staff I met, on the other hand, have no such luxury. Every day of their life is devoted to making sure that the schooling children like Riley, Jamie-Lee and Kalen receive in some way compensates for the poor start their home lives have given them. Every day, the staff give those children their all, in the hope that it will be enough to sustain them through the secondary years, in the face of other influences.

And, across the country, thousands of teachers do the same, often with little recognition and even less official support. I walked away after a week; they continue to walk back in, day after day and year after year. I hope this article goes some way towards expressing my awe for them all.

The names of the people, the school and some identifying details have been changed

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters