Life lessons

When I was first teaching in special education I was told the, perhaps apocryphal, story of a child learning to put on his own jumper.

Every day, this child worked to place it over his head, get his arms through the sleeves and adjust it so that it was comfortable. Eventually, he perfected the task and the teacher rang his parents so he could share the success with them.

However, the next day, a message came through that he could not perform the task at home. In fact, he was bemused by what he was being asked to do.

At school he was working with a green, woollen jumper. At home he was not. The child had learned to complete the task in a resource-specific manner and could not replicate it using different items.

It’s a story every leader in special education would do well to remember. It demonstrates how it is essential they look beyond the acquisition of knowledge within the security of a highly supportive and structured environment. The real success of a special school can be found in what happens elsewhere. How knowledge is applied in the often confusing, unpredictable and challenging world beyond the school gates. That’s not always easy - to do or to communicate.

Moving from the security of the classroom can be challenging and destabilising for some, and needs to be handled carefully. The last thing that we would want is for a child to have their confidence shattered by a poor experience of applying what they know in a confusing functional setting.

Overcoming challenges

Yet it is important that they are given the chance to overcome the challenges that real-life situations present. In assessing whether something has truly been learned, we need to establish whether it can be completed with different resources, at different times, in different locations and with different people.

We need to consider the variability of life beyond the school and the importance of building this variability into learning.

The jumper example is a good one. Another example of the impact of variability on learning is independent travel.

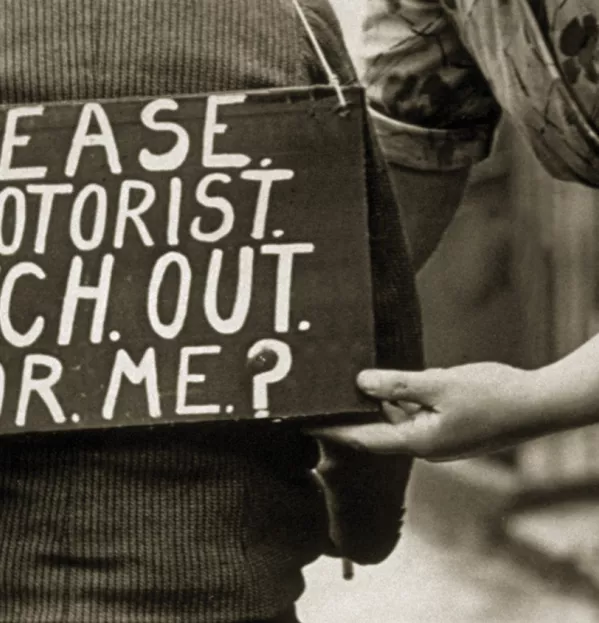

Being unable to decide where you want to go, when you want to go and completing the journey without the need for adult assistance can be very limiting. Not only can it restrict the control you have over your life, but it can potentially reduce the size of the world you have the opportunity to engage with.

A carefully-thought-through risk assessment, co-constructed with the child and their family, can make the seemingly impossible achievable. In making learning challenging but safe, it is important to think through the many variables that can make something successfully demonstrated in one context impossible to do in another.

Communicate success

Frank Wise School, in Oxfordshire, where I was previously deputy headteacher, explored this in some detail regarding travel. The factors they identified included distance, familiarity with the route, the complexity of the route, the types of transport used, the reason for the journey and the amount of time required. All of these can be combined in various ways in order to build confidence and capability, but failing to consider their influence on success can lead to the creation of significant barriers to achievement.

Once you have integrated real-world success criteria into your school, you then have to communicate that success.

It is relatively easy to articulate the capability of a student to those outside a school if you work in a mainstream setting. Most understand GCSE, A level and degree - any variations in those qualifications demand a tweak to messaging, but not a wholesale change.

But in the specialist sectors, things are more difficult. There is a greater challenge around communicating what pupils are able to do, something that is complicated by a social tendency to underestimate the potential of those with a disability.

As such, it is essential that special schools are well versed in highlighting the things that pupils are capable of. While a qualification may have a title that is unfamiliar or opaque, a list of evidenced competencies can have a much greater degree of clarity for those who do not know the person and can be tailored to specific contexts beyond the school, such as employment or independent living.

We also need to act as advocates of those we teach, seeking to draw the community into the school so that the perceptions of difference associated around disability are broken down. By working with the wider community, we can make it easier to see capability first, to understand that disability doesn’t mean no ability.

And we need to remember that learning isn’t easy and neither is applying what has been learned. If we want the time spent in school to have a lifelong impact on the children that we teach, then it is essential that together we take learning into life.

Simon Knight is director of education at the National Education Trust. He tweets @simonknight100

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters