A little more conversation?

It was 1.30am when Elena Kaloyanova arrived at The Sheffield College. The deserted street, she says, was “dark and scary”.

By 4am, however, a small crowd had gathered. Now, at 6am, hundreds of people are waiting.

Volunteers push a trolley along the queue, serving free teas and coffees. For the children waiting patiently with their parents, sweets are handed out along with chalk so they can draw on the pavements.

“These are just little things, but it makes it welcoming,” explains Steve Kelly, the college’s head of student services. “This can’t be yet another form-filling exercise for people to go through - we have to make it a nice experience. I find it really moving; these are people who have gone through so much in their lives, and it’s a privilege that they choose to come to us.”

By the time the registration desk opens, Kaloyanova has been patiently waiting in line for more than seven hours. She and the 500 other people who have congregated at the college’s Hillsborough campus are all there for the same reason: they want to learn English. Kaloyanova moved to Sheffield from Bulgaria, unable to speak any English, three years ago to be with her boyfriend.

In recent years, the number of people living in the UK whose first language is not English has increased significantly. This trend is especially visible in schools. According to the most recent census, England’s schools are teaching more than 1.3 million students with a first language other than English. The proportion of primary pupils speaking English as an additional language (EAL) has steadily increased from 12 per cent in 2006 to 20 per cent in 2017.

Funding appears, broadly speaking, to be keeping pace: the new national funding formula for schools will allocate a record £404 million for EAL students.

But there is a blind spot - and it is the reason why Kaloyanova had to queue through the night. The most troubling issue is not to be found in schools, where pupils who do not speak English will be given language classes and the opportunity to integrate. The people who appear to be largely invisible to policymakers, rather, are the families these pupils go home to at night.

The parents are cut off from the society in which they live because they struggle to talk to their neighbours, read the newspapers or even make an appointment to see the doctor. They struggle to become a part of their children’s education - a factor that is so crucial to a pupil’s success.

Three-year wait

The scene described above in Sheffield is by no means unusual. A survey by the charity Refugee Action, published last month, showed that, in almost half of providers, the waiting time for a place on an English for speakers of other languages (Esol) course was six months or more; in the most extreme cases, learners faced a three-year wait simply to learn English.

Evidence of this shortage of places can be detected across England. In London, over two-thirds of colleges report that demand for Esol courses exceeds supply. In Manchester, where 17,000 residents speak little or no English, there is a total of 4,000 Esol places - and a collective waiting list of 1,000 people.

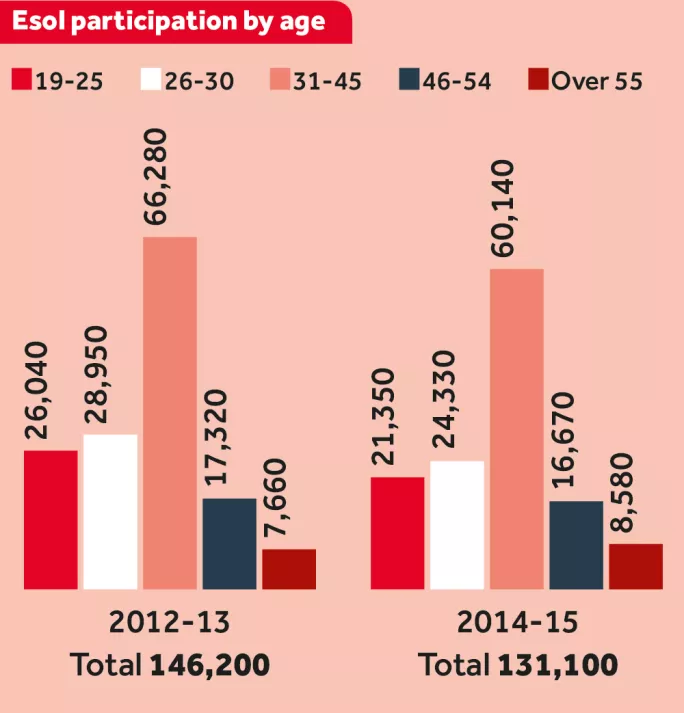

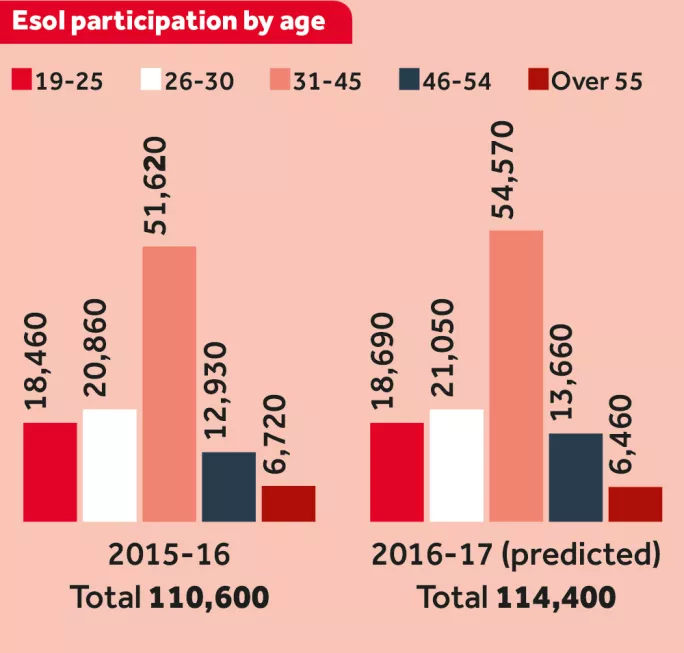

Funding available for Esol through the adult education budget has plummeted by 55 per cent over the past seven years, from £203 million in 2009-10 to just £90 million in 2015-16. Not surprisingly, participation has fallen from 180,000 to 110,000 during the same period. Demand for Esol courses, however, continues to rise. The current situation for the Esol sector is “the worst we can remember”, Natecla - the organisation that represents teachers of the subject - told Tes last month.

“I’ve never known Esol to be in such a fragile state,” said co-chair Jenny Roden. “The whole infrastructure is crumbling, and in some places they can’t find enough staff to teach the classes because many teachers are demoralised and are leaving the profession.”

Natecla has led repeated calls for a national strategy for Esol to coordinate provision in England, similar to those that exist in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. To date, these pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

While MPs across the political spectrum agree that it is vital for immigrants to be able to speak English, evidence from across the country suggests that a significant proportion are missing out on the opportunity to learn it.

So what are providers doing to tackle the obstacles to integration? And is there any prospect of Esol practitioners’ demands for a coherent national strategy - one that can match EAL tuition in schools so that whole families can benefit - bearing fruit?

In a quiet little corner of the cavernous Edmonton Green shopping centre, accessed via a staircase tucked away next to a halal butchers and a nail bar, is what David Byrne, principal of Barnet and Southgate College, describes as a “haven for the community”.

The North London college takes Esol seriously: of the 15,000 students that it enrols each year, 4,000 are on English language programmes. And this tiny, second-floor premises, dedicated to teaching local residents English in the heart of the community, is where many of them attend their classes.

A map of the world on display in the corridor is covered with dozens of learners’ passport photos showing the country each of them left to come to the UK. From Greece to Guyana, Sierra Leone to Sri Lanka, all corners of the globe are represented. On the opposite wall is an image of a tree, made up of yellow, green and blue paper leaves. On each leaf, a student has written why learning English is important to them.

“I want to talk to my doctor.”

“I want to talk to the council.”

“I want to watch English TV.”

The messages serve as a poignant reminder of the everyday interactions from which thousands of people living in the UK are excluded, simply because they speak a different language.

“Esol helps with interview for the UK passport,” states the message on another leaf.

“Esol helps my future and my children. Esol helps my education. I will find a job.”

The benefits of Esol may be easy to grasp, but understanding how provision is delivered is anything but. Funding is channelled through several government departments and local authorities; provision is delivered through an eclectic network of colleges, charities, schools and community-learning organisations. Some English classes are taught by experienced specialist teachers; others are led by enthusiastic volunteers with no formal classroom experience.

There is massive variation, too, in the types of people who turn up wanting to learn. Some are refugees and asylum seekers who may have fled war, torture or poverty; others have lived in the UK for decades, but remain unable to communicate with anyone outside of their diaspora. Some have little or no experience of formal education and may be unable to read or write in their own language; others have brought strong qualifications from their own country, and are capable of learning quickly and progressing to high-level jobs.

Creating a provision that works for all - and is affordable for providers - is clearly difficult. But Byrne believes that delivering English language provision to this diverse community is too important to ignore; he sets aside £4.5 million from the college’s annual adult education allocation to fund Esol.

“If you’ve got a community objective, you can’t ignore it,” he says. “Our surveys indicate learners won’t travel more than three or four miles - it’s predominantly right-on-the-doorstep provision. That’s why we wanted to be closer to the other agencies. Here, for example, you’ve got the job centre, the library, the big supermarket. People can walk metres rather than miles.”

The centre’s remit does not stop at English classes. “We act as a social service,” adds Byrne. “You’re helping people with housing benefit, understanding how local councils work, explaining to them how to register at the doctors. It’s all about the sharing of knowledge about what it’s like to live in the area. There’s a rich source of information. Our staff are willing and able to help.”

Tailor-made learning

As the majority of the college’s Esol learners are women, childcare is an obstacle for many. So the college works with local childcare providers to enable learners to attend classes. Timetables, too, are adapted to allow learners to fulfil family and religious commitments. Morning classes rarely start before 9.30am, so students can take their children to school beforehand; evening classes start later, so they have time to cook for their families before coming to college.

As well as having to leave classrooms empty at peak times, the college is also used to taking a financial hit on tuition fees. While the government fully funds Esol for most unemployed people, it only covers part of the cost for other learners, leaving providers to decide whether to cover outstanding costs themselves or pass them on to the learner.

Problems can arise when a learner’s benefits status changes mid-course, meaning they may no longer be eligible for free tuition. Hundreds of learners find themselves in this position each year, says Byrne.

“Are we honestly going to say, as a college, that we will let the student go because they’re not funded? No. It’s a no-brainer, you’ve got to pay for it,” he insists. “What it means, though, is that our margins on Esol are tiny.”

But while providers are quick to complain about what Refugee Action describes as the “chronic underfunding” of Esol, Sue Pember, director of policy and external relations at Holex, the umbrella body for adult and community learning providers, believes the picture is more complex, citing the £200 million in the adult education budget for 2016-17 that remained unspent. So if there is demand for Esol, and funding available for it, why are providers not delivering more classes?

The reason, Pember says, is the effect of regulator Ofsted’s influence: statistically, Esol learners are among the least likely to complete a qualification. As a result, colleges could end up being penalised by the inspectorate and in national data for taking on too many students who risk dragging down their success rates.

She says: “The rules of engagement and the performance arrangement have a negative impact on recruitment - you can’t take a chance on a person. [Providers] need to recruit people who are certain to stay the course.”

And this, believes Pember, has cultivated a cautious approach to Esol recruitment.

One consequence of this is that many parents left without English language skills struggle to play a part in their children’s education. The impact of this approach can be witnessed in schools across the country, with parents struggling to understand official school communications and often relying on their children to act as translators.

On the Esol tree on display at the college’s Edmonton campus, one theme recurs time and time again: “I want to help my children with their homework.”

While learning English is a given for immigrants of school age, their parents often end up missing out - both on language classes and the opportunity to support their child’s education. One way many providers address this issue is through family learning, in which parents and children learn English together, often in a school setting.

Family learning became an established policy under the Labour government from 2001 onwards; at its peak, funding for family literacy, language and numeracy programmes reached £25 million a year between 2008 and 2011. But its prominence has dropped on the national stage, with funding largely now provided through local authorities for individual projects.

A report on Esol in London, however, published in May by the Learning and Work Institute, highlights a “sound correlation between the improvement of parents’ English language with the literacy progress made by their children in school”.

Earlier research by the institute found that family learning could increase the overall level of children’s development by as much as 15 percentage points for those from disadvantaged groups, and provide an average reading improvement equivalent to six months of reading age.

A pilot project in Waltham Forest in 2014-15 led to 126 parents taking part in family English language courses in local schools. This “enabled second-language speakers to integrate more with their children’s school community, and more effectively engage with local facilities, services and other parents in their schools”, said the institute.

A major study is currently ongoing to monitor the impact of a family learning programme designed to improve the literacy skills of both Reception-class pupils and their parents. This £2 million research project is being funded by the Education Endowment Foundation, Unbound Philanthropy and the Bell Foundation. The results of the randomised control trial across 140 primary schools are expected to be published next summer.

‘Building bridges’

Karen Dudley, an Esol specialist at social enterprise Learning Unlimited, which is coordinating the programme, says: “We’re looking at how this can make a difference in supporting parents with their own language but, just as importantly, understanding the education system in the UK and how they can support their children’s learning. It’s about helping to minimise the communication barrier with school staff, whether it’s the teacher, teaching assistant or people at reception. It’s about building bridges and giving parents the confidence to interact.”

For now, however, conclusive data demonstrating the impact of family learning is limited. In the meantime, what can the government do to address the challenges facing Esol and allow provision to flourish?

For Pember, the answer is simple: England needs a clearly communicated, cross-departmental strategy for Esol. And she should know. Having served as the lead director for adult and further education in the former Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, she has seen first-hand how Esol has slipped down the list of political priorities.

“The new migrants do not know whether they have an entitlement to learn English,” she says. “There’s no communication of this, no promotion at all. Ministers don’t even mention it in speeches. Why can we not have an Esol policy in England? We need one so the learner knows what they’re entitled to, the provider knows what they can do, local authorities are clear, and we don’t get duplicated initiatives or removal of funds from the Home Office, the Cabinet Office or the Department for Communities and Local Government. No politician wants to take the lead on an Esol strategy.”

After years of being ignored, though, there could finally be a ray of hope for Esol provision. Back in July 2015, David Cameron, then prime minister, commissioned a review of “opportunity and integration” in the UK amid growing panic about radicalised young Britons heading to the Middle East to join the so-called Islamic State. The report was written by influential mandarin Dame Louise Casey. The Casey Review, published last December, made explicit the “fundamental” importance of a shared language to enable the integration of immigrants. It also called for “sufficient” funding to be made available for community-based English classes through the adult education budget.

The government “should also review whether community-based and skills funded programmes are consistently reaching those who need them most, and whether they are sufficiently coordinated”, the report added.

Almost a year on, the government’s response has yet to be released. But Tes understands that this, and a new integration strategy, are expected to be published imminently. Could this be the best hope of a national approach to Esol finally arriving?

The indications are that the message may be starting to get through. In August, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Integration called for a “comprehensive strategy to promote English language learning”. Last month, former education secretary Nicky Morgan joined the debate, writing that investing in English classes “will unlock people’s potential to work, volunteer, socialise with their neighbours, and make a full and active contribution to our society”. The signs appear to be encouraging.

But for Pember, it is time for words to be backed up with action: “We need someone to say, ‘This is really important, we’re putting in a lot of money, we need better coordination and we’ll put some work into getting it right.’

“All we need is the will of the government to make it happen.”

Stephen Exley is Tes’ further education editor. Additional reporting by Sarah Simons

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters