Mastering the art of good teacher explanations

Teachers, if we look at things simplistically, are explainers. They explain knowledge, they explain ways of being, they explain life. And they are, on the whole, very good at it. But though most teachers are already good at explanations, it would seem sensible to lay out how every explanation can be as excellent as possible.

That’s not just because explanations have become increasingly seen as something some teachers are just gifted at, like a dark art, but because, in the current crisis, good explanations are more important than ever before. They may be the only bit of teaching a child receives at home, and it’s likely they will have to be transferred from classroom delivery to print or online delivery, so we need to get the essentials right.

What’s the first consideration when forming an explanation, then? One word: audience. “The first thing to observe is an explanation has an audience. An explanation isn’t good or bad in itself - its quality depends on whether it makes sense to the people it’s intended for,” says Alan Schoenfeld, the Elizabeth and Edward Conner professor of education and affiliated professor of mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley.

“An explanation that a mathematician provides to another mathematician may be correct and comprehensible to that other mathematician, and completely incomprehensible to a student.

“Similarly, a clear explanation given by a doctor to another doctor might be barely comprehensible to the average patient. A good explanation of an idea to a fourth grader (Year 5) could be tedious to an eighth grader (Year 9), and insulting and not adequately nuanced for a senior (sixth-former).”

Essentially, any formation or judgement of an explanation needs to consider the age, working attainment, special educational needs and disability (SEND) profile and subject discipline of the recipient.

That means we need to have a good working knowledge of every student in our classrooms, says Neil Mercer, director of Oracy Cambridge, also known as the Hughes Hall Centre for Effective Spoken Communication, at the University of Cambridge. “Especially in an educational context, a good explanation is one that takes account of what the recipient knows and does not know,” he says.

“An effective explainer doesn’t waste time telling the recipient things that they already know or do not need to know, but they also do not make false assumptions about the recipient’s existing level of knowledge and understanding, which means the explanation is pitched too high and will not make sense.”

With 30 pupils awaiting that explanation, how do you make sure you know enough about each of them? Teachers need to employ their “uniquely human ‘theory of mind’ capabilities” to make judgements about the “state of knowledge and understanding of the recipient”, says Mercer.

“This should be based on what the learner has already said or done, or the teacher’s experience of what a Year 6 student, for example, usually knows about [the topic].”

You will also need to consider what “engaging” looks like for each child. The tone, delivery or elements of storytelling that one child finds engaging may not be the same for another.

In an ideal world, this would probably mean unique explanations for each child, but that’s just not viable, so finding the best fit for larger groups, or even the whole class, should be the aim.

Shared ground

However, getting more complex points across in an accessible and engaging way requires more than simply pitching your subject knowledge at the right level and knitting together a decent narrative.

“Obviously, good explanations have to be correct but, in addition, they have to say why something is true and leave the audience understanding those reasons,” Schoenfeld explains. “They start by meeting the listeners where they are, on shared ground. And then they move forward in steps that the listeners can get their heads around.”

This means not just “telling them” but working with them to build knowledge in a collaborative way.

“Ultimately, the listeners should have internalised the information so that they can reproduce the substance of the argument in their own terms,” continues Schoenfeld. “So, in effect, a good explanation is dialogical - it involves a give-and-take that ensures, at the end, that the learner has internalised the substance of the reasoning that produces the desired understanding.”

So not having a strict script but being flexible with your explanation to match the reaction, and developing understanding of those in front of you, should be the aim.

“‘Explaining to’ presumes a one-way interaction and undermines the sense-making potential of the individual,” adds Schoenfeld. “What you’d like is for classrooms to serve as cultures of sense making, in which students are supported in building arguments and explanations; building, in meaningful ways, on what they know.”

If that all sounds complex, Schoenfeld has a tool that can help. Through his research, he has developed the Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU) framework (truframework.org). According to the TRU framework, the quality of a learning environment depends on the extent to which it provides opportunities for pupils in what it calls five “dimensions”:

- The content: this is not just about developing accurate knowledge - what is taught should also include disciplinary skills and habits of mind.

- Cognitive demand: content for students should put them in a state of “productive struggle” - that is, the content should be pitched just right to stretch their current knowledge and skills.

- Equitable access to content: this is all about creating a culture in which every student can listen to, engage with and process the information offered equally.

- Agency, ownership and identity: good explanations should be about pupils absorbing content, then rephrasing it, engaging with it and owning it.

- Formative assessment: the extent to which what you are saying is developing the pupil and how far you can ensure that development continues.

The ownership point is one reiterated by Barak Rosenshine, a former professor in the department of educational psychology at the University of Illinois. His seminal paper, “Principles of Instruction”, makes it clear that an extended single monologue followed by practice is not the best idea.

Instead, he advocates a more fragmented approach, presenting new material “in small steps with student practice after each step” ; and only presenting “small amounts of new material at any time, and asking a “large number of questions and check[ing] the responses of all students”.

Rosenshine writes: “Questions help students practice new information and connect new material to their prior learning. Compared with the successful teachers, the less effective teachers gave much shorter presentations and explanations, and then passed out worksheets and told students to solve the problems. The less successful teachers were then observed going from student to student and having to explain the material again.”

Working memory limitations

There is robust science behind avoiding too-long explanations. One of the issues that teachers have to overcome is the limitation of working memory - our ability to hold things in our minds for a brief time while getting on with, or learning, other things.

“Our working memory … is small. It can only handle a few bits of information at once - too much information swamps our working memory. Presenting too much material at once may confuse students because their working memory will be unable to process it,” Rosenshine writes. “Therefore, the more effective teachers do not overwhelm their students by presenting too much new material at once.”

As Susan Gathercole, a professor of psychology at the University of Cambridge and a leading expert on the cognitive mechanisms of short-term and working memory, told Tes in September that teachers do not always take into consideration these limitations when giving explanations.

For one of her early studies, Gathercole observed classes and wrote down the sequences of instructions that primary teachers were giving to their pupils. She often found that the instructions were incredibly lengthy and complex.

“We took some of the instructions and, as part of a project at Durham University, read them out and got university students to repeat them back,” Gathercole said. “Quite often, they were just too lengthy even for them to repeat, even though it came from a class for six-year-olds.

“So some teachers maybe aren’t quite so good at judging the amount or complexity of information that a child can remember.”

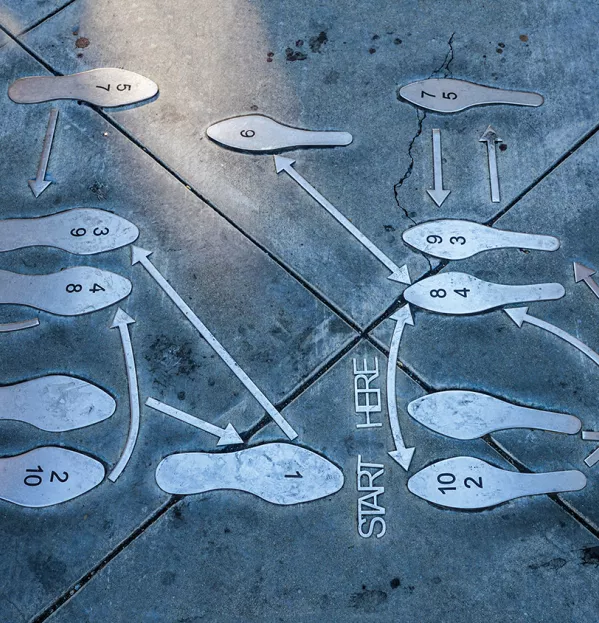

There are ways around this. Gathercole noted that the use of diagrams depicting instructions as a reference for students who need it, or getting pupils to work in teams, can be effective ways of increasing comprehension. “In one Year 1 classroom, a teacher had provided audio recorders for each child and they used to speak the instructions and record them so the child could listen back to them when they needed and refresh the information that they had lost,” she said.

So what makes a good explanation? Know your audience - not just the right content but also the right delivery. Ask yourself, “What does great storytelling and great intonation look like for them?” Break up your explanations and ensure that pupils get a chance to own what you are explaining.

That makes it sound easy. It’s not. And trying to do all of these things outside the familiar classroom setting, via printed booklets or over video-conferencing tools, will make things even harder. But, hopefully, the above will reduce the stress and ensure explanations become less of a dark art for the millions of teachers who rely on them.

Now, did we explain all that clearly enough for you?

Chris Parr is a freelance writer

This article originally appeared in the 27 March 2020 issue under the headline “Tes focus on...Good explanations”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters