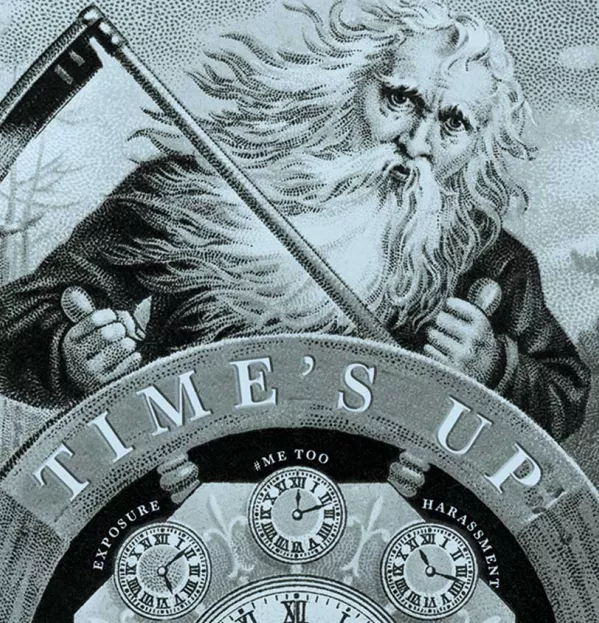

A message to my sexual harasser: your time is up

In the wake of revelations surrounding Harvey Weinstein’s sexual harassment of Hollywood actresses, the #MeToo movement has become a beacon of hope for women around the world. And perhaps nowhere is the message of this movement more powerful than in schools, where children form lifelong attitudes about one another.

But all is not well at the chalkface, as a recent survey by education union NASUWT shows. It reveals that more than eight in 10 teachers believe they have suffered sexual harassment or bullying in the workplace, while one in five says they have been sexually harassed at school by a colleague, manager, parent or pupil since becoming a teacher.

As a result of such incidents, 43 per cent of teachers say they have suffered loss of confidence; 38 per cent have experienced anxiety and/or depression. Nearly half have made changes to their daily routine to avoid the harasser, while almost a third have felt pressure to change their appearance or style of clothing in an effort to avoid further aggravation.

Sexual harassment and behaviours that fall under this category include inappropriate touching; invasion of privacy; sexual jokes; lewd or obscene comments or gestures; exposure of body parts; being shown graphic images; unwelcome sexual emails, text messages or phone calls; sexual bribery, coercion and overt requests for sex; sexual favouritism; being offered a benefit for a sexual favour; and being denied a promotion or pay raise because you didn’t cooperate.

My story isn’t one of physical harassment, but it has still left me feeling violated and used. The truth is that many men - gay, straight, queer, bisexual and others - also suffer sexual harassment and assault of varying degrees of severity. These range from objectifying remarks about their appearance to sexual suggestions and invitations that are out of place, touching and genuine assault. As a gay man, it’s difficult to feel you can come forward to talk about harassment when you are already trying to break stereotypes, fight for equality, but also be treated like your heterosexual counterparts. The conflict is deafening.

It started when I received a connection via LinkedIn from a male school leader in Scotland. Having noted a few mutual connections, I accepted, and received a private message from him thanking me for connecting.

The discussion started professionally, but soon became sexual and awkward. A man of power was using his status to try to meet me, and to fulfil his sexual fantasy and fetish. Two things crept into my head while the conversation was happening: 1) Why is this happening to me? 2) How do I respond?

The typical me would have told him where to go, but I thought, “What if he needs to interview me in the future?”, “What if I need to work with him?”, “If I tell, would people believe me?”

‘Persistent and predatory’

At first, I laughed it off, but he became quite persistent and was contributing to the anxiety I suffer from generally. This shouldn’t be happening in education, I thought - we’re professionals, we have integrity - so why is it happening? His fascination with what I was wearing, the bulge in my jeans (which I later found was a common thread between those he had made contact with) and how my “arse” looked made me feel physically sick, as my partner sat upstairs unaware. But, again, the thought of “What if I need to work with him in future?” came to mind.

I said to him that I thought it was unprofessional and awkward that this was happening over LinkedIn. He apologised and suggested we move to WhatsApp (as if, in his mind, that made things more casual).

I put a message on my personal Facebook saying how appalled I was, and a friend - another gay educator - private-messaged me, saying he felt he knew who it was, as the scenario was very similar to one he’d encountered. It soon became clear it was the same school leader and, like me, he had also approached my friend via LinkedIn, where the conversation became persistent and, in my friend’s word, predatory.

We discussed how unprofessional the behaviour was, but I also found out that the leader in question was married, which threw an added obstacle into the mixture.

My gut was saying “Phone the GTCS” (General Teaching Council for Scotland), but my head was holding back. I can’t be responsible for outing someone and I believe that, even with this horrible situation, telling someone about your sexuality or gender identity must always be a personal decision. No person has the right to take that decision away. Publicly outing someone robs them of the chance to define who they are in their own terms.

Not wanting to discuss the matter with the GTCS, I posted on Twitter in the hope that he would back off and understand that this type of behaviour wasn’t right. After being called out, he deleted me as a LinkedIn contact.

Two weeks later, a probationer contacted me: a similar discussion, similar language, similar uncomfortableness. But he didn’t want to report it, as he had just been given a contract with the council that the school leader works for. This probationer reached out to me for support and to tell someone.

The episode has left me feeling ashamed; it’s been humiliating to be made to feel like an object - and also that somehow I invited this conversation to happen by accepting the school leader’s connection. Sexual harassment can be a humiliating experience to recount privately, let alone publicly.

As human beings, we want to believe that we have control over what happens to us. When that personal power is challenged by a victimisation of any kind, we feel humiliated. We believe we should have been able to defend ourselves. And because we aren’t able to do so, we feel helpless and powerless. This powerlessness causes humiliation.

When I was talking to the probationer, he was trying to downplay it and minimise the situation until I said “If you were a woman, would this be acceptable?” To which he responded “no” and then said: “The message didn’t sit comfortably with me. Put it this way, I keep my private life private and this potentially put that at risk if I need to report it.”

The GTCS is there to protect us, to make us accountable, but you still fear repercussions - fear of losing your job, that you won’t find another job, that you will be passed over for a promotion, of losing your credibility, of being branded a troublemaker, of being blackballed in our industry, for your physical and/or mental safety.

So if you are the school leader in question and you are reading this, be aware that you are making people uncomfortable, that what you are doing is not correct, and just because we are men, it doesn’t make it any less acceptable than it is for the many women across the country who face this sort of behaviour. As a school leader, you should have vision and values - not be abusing your role to meet some sort of fantasy. And know that in 2018 it is OK to be gay, but it’s not OK to sexually harass anyone. Time’s up!

John Naples-Campbell is a faculty head of expressive arts in Aberdeen

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters