Private finance legacy slows curriculum reform

Private-finance deals that were signed a generation ago are leaving Scottish schools struggling to adapt to Curriculum for Excellence and landing them with exorbitant bills for essential equipment, a Tes Scotland investigation reveals.

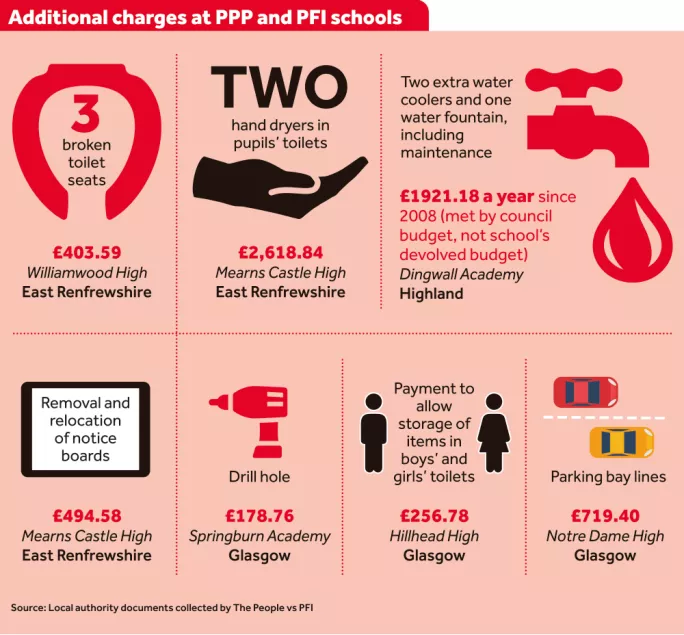

The charges include £180 to drill a hole in a wall, nearly £500 to move noticeboards and more than £1,200 to hang some papier-mâché lanterns, all affecting schools built under public-private partnership (PPP) and private finance initiative (PFI) schemes.

Teachers are warning that the money is being diverted from essential classroom resources such as books.

Meanwhile, headteachers say the schemes are restricting their ability to modernise timetables and adapt classrooms in order to provide a wider range of subjects, which is a crucial element of CfE.

Campaigning group The People vs PFI shared detailed information, which was obtained from 11 Scottish local authorities on spending associated with PFI/PPP schools, with Tes Scotland.

It revealed the extra costs that fall outside the contractual arrangements, which often give schools no say over where to source additional items or services from.

These additional costs can be small - for example, £41.56 to hold a two-hour fundraising event for Malawi at one school - or much larger, such as more than £24,000 to adapt a disabled toilet.

Funding ‘fiasco’

The People vs PFI argued that this is only one part of the “Scottish PFI schools fiasco”.

Spokesman Joel Benjamin said: “There is evidence from numerous schemes that PFI contractors are not even doing what they are being paid for within the contract, let alone the additional remedial work that is considered to be outside the scope of the contract - from which contractors expect additional taxpayer funding.”

Several teachers have shared their frustration with Tes Scotland about their schools’ PFI and PPP contracts. A delegate at last week’s annual meeting of the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association, who wished to speak anonymously, said that if a chair was missing or a pupil vomited, teachers had to call a central helpline: they were unable to simply ask the janitor to help, or to get a mop or bucket themselves.

She said: “It’s nice to come in and find the floors polished or renewed but I know the council will have been billed for that, and I’m an English teacher and I can’t buy books. You’re just sitting there thinking, ‘How much have they spent on that?’”

Another secondary teacher in the Central Belt told Tes Scotland about a project where pupils had made Chinese-style papier-mâché lanterns. The school wanted to brighten up the assembly hall by hanging them from the ceiling, but dropped the idea after being quoted around £600 for installation and another £600 a year for “maintenance”.

There are around 350 PFI and PPP schools in Scotland. The schemes were introduced under Labour from the late 1990s to fund big building projects. Instead of having to pay for a new building with public money upfront, a private company is paid an annual fee to construct it and provide ongoing maintenance.

In 2011, the Scottish Parliament reported that these “unitary charges” for schoolbuilding projects would cost more than £500 million a year by 2012.

On top of the annual charges, contractors can charge schools for additional services such as changing the use of a room or buying extra equipment.

The SNP launched the Scottish Futures Trust as an alternative to PFI/PPP when it came to power in 2007, attempting to limit private profit from building projects and involve public sector bodies more. While no stranger to criticism, it has generated less controversy than PPP and PFI.

School Leaders Scotland general secretary Jim Thewliss said the Scottish Futures Trust model, favoured in recent years, had given headteachers a “much better say” over the design and use of school buildings.

Even contractors for the initial wave of PPP and PFI schools now appeared more willing to listen to teachers’ concerns, said Mr Thewliss, although a headteacher still sometimes had to decide between “fixtures and fittings or educational resources”, with most extra costs met from schools’ budgets.

However, he said the move to a broader curriculum - a key part of CfE - was being hampered by strict contractual rules on how school bulidings could be used.

Limiting students’ options

Rigid contracts were restricting the subjects that could be offered by schools, for example by limiting their ability to install food preparation equipment for hospitality classes. He said this was also undermining the Developing the Young Workforce agenda, which aims to improve the status of vocational subjects.

Under the PFI schemes, headteachers also highlighted difficulties adapting buildings for subjects such as hairdressing and computing.

Adjusting the agreements can involve a “nightmare of negotiation”, Mr Thewliss said.

Michael Wood, general secretary of education directors’ body ADES, said earlier projects were good value overall, given the poor state of many schools around 20 years ago.

He added: “The bottom line is that, every day, we have got young people sitting in fantastic buildings.”

A Scottish government spokesperson said: “We share the concerns around the flexibility and the value for money offered by historic PFI contracts which offered a bad deal for the public purse.

“The Scottish Futures Trust has been working on behalf of ministers to assess contract management and improve performance and efficiency within a number of operational contracts. The management of a PFI contract however, is a matter for each public sector procurement body which awarded it.”

The Scottish Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee last week announced a short inquiry into the safety of school buildings, starting on 14 June, after 17 PPP schools in Edinburgh were temporarily closed last year due to building defects.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters