Question your questioning

Teachers ask questions. A lot of questions. It’s how they try to gain an understanding of what their pupils understand. It’s part of how they decide what to teach, to whom, and when.

In teaching, questioning matters.

Most teachers tend to worry that they ask too many closed questions. They consider open questions to be better for discussion or enquiries - better for getting their students thinking - while closed questions are limited to testing knowledge.

But what if these assumptions are wrong? Now that’s one question that will take some time to answer.

Let’s start with another question: are the following questions open or closed?

a) What is the answer to the sum 2 + 2?

b) What is poetry?

c) What can you tell me about Paris (the capital of France)?

d) Is the mind the same as the brain?

Most people would say that a) is closed and b) is open; c) is usually more contentious. But it is d) that is the most controversial.

Though attending to the questions themselves is helpful, it is not the whole story. That comes from the mindset of the teacher

Question d) appears closed because it elicits a short one-word answer, usually “yes” or “no”. But d) appears to be open because it is contestable: there is much to discuss.

(Quick clarification: a closed question is not the same as a leading question, where one strongly implies or states the answer being looked for in the question asked.)

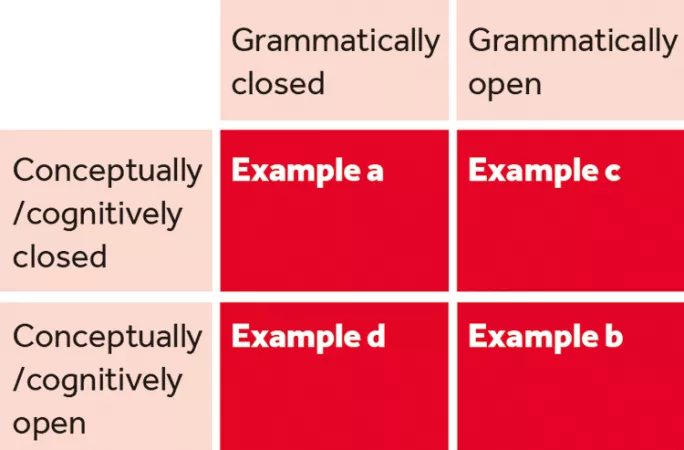

So d) is both open and closed, but this makes sense only with a distinction between two kinds of open and closed question: grammatical and conceptual. The first of these refers to the structure of the question, the second to its content. So, to put this in pictoral form:

Type-d questions are the best for enquiries or discussion, though they are what would normally be thought of as “closed”. They are only grammatically closed, however; they’re open with regard to what is being discussed.

You might think “But if they are grammatically closed, isn’t the discussion in danger of drying up, with sparse phrases such as “yes” and “no”?”

I have a simple strategy to offer here, which I call “the question X”. If a closed question looks like this “>” and an open question looks like this “<” then my recommendation above, a “d” style question, looks like an “X”.

It gives the best of both worlds: the focus and specificity of a closed question (this, after all, is why teachers use them) and the inviting, elaborating character of an open question. But to make it work, you need to open the question up. So you now need some “opening up” strategies.

Opening up questions

The following is an example of a grammatically closed but conceptually open question: “Is it ever right to lie?”

Here are some ways to open it up:

* Child says: “Yes” or “no”

* Opening-up strategy: Justification

* Example: “Could you say why?”

* Child says: “It depends”

* Opening-up strategy: Dependence

* Example: “Could you say what it would depend on?”

* Child says: “You can say things that aren’t true.”

* Opening-up strategy: Elicitation

* Example: “Could you say a bit more about that?”

* Child says: “It’s the situation, isn’t it?”

* Opening-up strategy: Clarification

* Example: “Can you say what you mean by that?”

* Child says: “Lying is different from being wrong.”

* Opening-up strategy: Explanation

* Example: “Can you explain in what way lying is different from being wrong?”

* Child says: “There are different kinds of lies: there’s little lies, like if you […] and big lies, like when you […]”

* Opening-up strategy: Implication

* Example: “So, what do you think that that tells us?”

* Child says: “What do you mean by ‘lie’?”

* Opening-up strategy: Socratic question to group

* Example: “What do we mean by ‘lie’?” or “what is a lie?’”

So questions can be both closed and open. But having considered the question aspect of open and closed questions, now I’d like to address the psychological dimension.

Though attending to the questions themselves is helpful, it is not the whole story. That comes from the mindset of the teacher/questioner, whether s/he has an open-question mindset (OQM) or a closed-question mindset (CQM).

The latter is where the teacher has already decided the issue and then questions to find a specific answer, commonly, “guess what’s in my head” questioning (GWIMH).

An OQM teacher, on the other hand, questions to find out what the students in fact think and then to find out why they think it. This is how the teacher gains an understanding of the student’s understanding, including, crucially, what they don’t understand - which is essential for progress in learning.

So, CQM (GWIMH questioning) is:

* Teacher: ”What is the answer to the sum 2 + 2?”

* Student A: ”Is it 22?”

* T: ”No. Anyone else?”

* Student B: “Is it four?” (The reason has not been asked for; it could be “four is my lucky number”.)

* T: “Yes. Well done!”

Now look at OQM questioning:

* T: ”What is the answer to the sum 2 + 2?”

* S: “Is it 22?”

* T: ”Now that’s interesting. Can you explain how you got 22?”

* S: ”Well, if you put a 2 next to another 2, you get 22.”

* T: ”OK, I see what you’ve done there. Well, you have added in a way, but it’s not the kind of adding that we’ve been doing.”

The question “what is the answer to the sum 2 + 2?” is surely the ultimate closed question, yet, as we see above, one may treat the question in an “open” way. So an OQM is independent from the question itself.

As you can see, the question of whether a question is open or closed is not as closed as you might have thought and, in fact, is rather open. Let’s look at it again.

Here’s an open question with an OQM:

* T: ”What is poetry?”

* SA: “Poetry’s rubbish!”

* T: ”OK. Why do you think poetry is rubbish, Chantel?”

* SA: “Because it’s difficult to understand.”

* T: ”Yes, Owen?”

* SB: ”Just because something is difficult to understand, doesn’t mean it’s rubbish. My mum doesn’t understand the music I listen to, but it’s not rubbish.”

* SA: ”It’s rubbish to her, though. Poetry’s rubbish to me.”

* T: ”What do the rest of you think about that, ‘Poetry is rubbish’? [She writes it up on the board.] Have a moment to discuss it with each other.”

Now for an open question with a CQM (a classic case of GWIMH questioning):

* T: ”What do you notice about this poem?”

* SA: “It’s rubbish!”

* T: ”Anyone else?”

* SB: “It’s boring!”

* T: [Sarcastically] “Thank you for that helpful analysis, you two. Anyone else?”

* SC: “It doesn’t rhyme.”

* T: “Well done! Yes, as we can see from this wonderful poem, a good poem doesn’t always have to rhyme…”

Now, this next example shows how the first part of this article connects with the second. Here you will see how closed questions may be used effectively for an open discussion.

* T: “Is this a poem?” [Grammatically closed but conceptually open question.]

* SA: ”No.”

* T: ”Can you say why not?” [Opening up the closed question for justification.]

* SA: ”Because it’s not long enough?”

* T: ”Does a poem need to be a certain length, then?” [Closed question.]

* SB: “Not really.”

* T: “Go on…” [Opening up with a prompt this time.]

* SB: ”Because a poem can be any length?”

* T: “So, do you think this is a poem?” [Anchoring back to the main question.]

* SB: ”No.”

* T: “Do you mind saying why not?” [Opening up for justification.]

* SB: ”Because it is not a complete thought.”

* T: [Echoing.] ”‘It’s not a complete thought.’ Could you say what you mean by ‘a complete thought’?” [Opening up for meaning…]

Perhaps the most interesting example is also the most realistic, whereby the teacher is using an open question, but for a closed agenda (for example, to meet her aims and objectives), yet maintaining (perhaps within reasonable limits owing to time pressures) an OQM:

* T: ”What is poetry?”

* SA: ”It rhymes.” [Teacher writes “rhyme?” on the board and ticks it off her list.]

* T: “Thank you. What does everyone else think about that?”

* SB: “Poetry doesn’t have to rhyme but it has to have rhythm.” [Teacher writes “rhythm?” on the board and ticks it off.]

* SA: [To SB] “Why does it have to have rhythm if it doesn’t have to rhyme?”

* SB: “OK, maybe it needs one or the other - it’s just prose if it’s got neither.”

* SC: “I think a poem is a worded thought.”

* T: ”What a lovely expression, ‘a worded thought’. [She writes up “a worded thought” on the board.] Can you say more about that? It’s certainly not on the list of things I have here! [Pointing to her lesson plan document then leaning forward to listen with an encouraging smile.]”

* SC: ”Something you think that you find the right words for…”

It seems simple enough when you write it out like this, but in reality, questioning your questioning is a little more complex than it first appears. You might be ticking off the box marked “using open questions” but, in reality, you may have a CQM that renders an open question closed. You might also be avoiding closed questions when, with an OQM, they could be the best tool for the job.

We have to be more aware that we might be using an open question, but that doesn’t mean that it is an open discussion. Using a closed question(s) doesn’t mean that the discussion is closed, neither does it necessarily mean you will elicit the knowledge you are looking for or that the child really holds.

So let’s question our questioning more. Let’s think about and better plan how we use our questions. Let’s give questioning the respect, in the form of time and consideration, that it deserves. Because teachers ask a lot of questions - and in teaching, questioning matters.

Peter Worley is a teacher, CEO of The Philosophy Foundation, president of SOPHIA (the European foundation for the advancement of doing philosophy with children) and a visiting research associate at King’s College London. His latest book is 40 Lessons to Get Children Thinking. He tweets @the_if_man

The ideas above have been adapted from two papers published in the Journal of Philosophy in Schools: bit.ly/PWorley

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters