Schools fighting fires in the oil capital of Europe

It’s the doomsday scenario for teachers: having no choice but to send pupils home. Yet a few months ago, that prospect was painfully close to reality in Aberdeen.

About four years ago, the city was hit by a perfect storm: the pupil roll was soaring, baby-boomer teachers were retiring en masse and new teachers were being driven away by a buoyant oil and gas industry that put living costs in Aberdeen beyond the means of young graduates.

There were about 100 teaching vacancies, and the city tried myriad ideas to try to plug the gap. Golden hellos were promised, a recruitment campaign targeted teachers in Canada and council houses were refurbished and offered at knockdown rates.

Yet the situation got worse. Just before this year’s summer break, there were 120 teaching vacancies. The implications were stark, as education and children’s services director Gayle Gorman recalls: “We weren’t confident that we’d have enough teachers to open all our schools at the beginning of term.”

That prediction was based on the past experience of many young teachers initially agreeing to work in Aberdeen, only to pull out late in the day upon discovering that it might cost £1,200 per month to rent a one-bedroom flat in one of the city’s less salubrious areas.

Schools on the brink

Education chiefs were bracing themselves for the worst - knowing that, as well as sending children home, other drastic measures might include forcing pupils to move school.

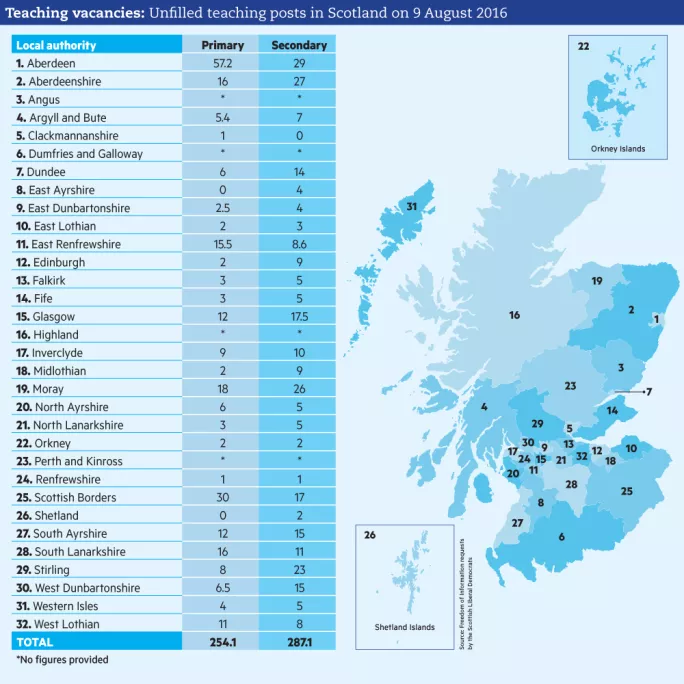

But that never happened. After all the schemes designed to resolve the problem (see “How Aberdeen has tried to tackle the crisis” box, below), it was ironic that the saving grace was far beyond the remit of the council: the tumbling value of oil. As it fell, so the price of property and living in Europe’s oil capital came down - and it became easier to hold on to teachers. Towards the end of September, there were 78 teaching vacancies, although Aberdeen is still suffering far more than Central Belt authorities (see table, below).

And the city is far from out of woods. The most pressure is on primary schools - which had nine extra classes at the start of this year - while “huge gaps” have opened up in secondary subjects. Computing, English, home economics, modern foreign languages and physics have, at various times, felt the strain.

It was ironic that the saving grace was the tumbling value of oil

Gorman says the city has learned to be “realistic and manage expectations”. Rather than offering pupils courses without being sure if there will be a teacher in place, schools are tending to make decisions earlier about whether to run them or not.

Several hundred secondary pupils this year cannot pursue certificated courses that they signed up to - two schools, for example, withdrew computing at the start of term (see “The most difficult situation I’ve ever faced” box, below). And this, adds Gorman, is despite Aberdeen putting an emphasis on salvaging courses for senior pupils by removing courses from the broad general education.

Much of the burden of the recruitment shortfall is falling on headteachers and their deputes. “In our primary estate, there isn’t a management team that isn’t committed quite highly now to teaching,” says Gorman. Some deputes are teaching full-time and most heads, bar a few in secondaries, are also teaching.

And that is happening as Scotland deals with a well-documented crisis in headteacher recruitment. A few weeks ago, in Aberdeen’s 59 primary and secondary schools, there were 19 headteacher vacancies, with acting heads filling 15 of those posts.

Combined responsibility

Alison Cook, headteacher at Woodside primary, has also taken on an acting headship at Heathryburn primary, with a combined responsibility - including nurseries - for more than 800 children.

She recalls times when it was routine to get 30 or 40 applications for a teaching post. Now, even with financial incentives, you might get one eligible applicant. Cook, a headteacher for 14 years, admits “this is the toughest it’s ever been”.

The goodwill of others has become crucial: council education officers have stepped in to take classes, and “incredibly” supportive headteachers of other schools have lent staff. “If we hadn’t had support from the council, we would have been [in situations] where we had to send children home,” says Cook.

Some pupils may have up to five teachers over a year, she adds, while depute heads are constantly teaching classes, leaving heads to handle essential remits such as curriculum improvement on their own.

‘We would have been in situations where we had to send pupils home’

“I feel a great sense of frustration because I’m not able to do for the children and the staff what I would like to do, because we don’t have the capacity,” says Cook.

Back at council headquarters, Gorman acknowledges that opportunities for curriculum development and innovation in schools are “severely diminished” by the lack of teachers in front of young people.

Necessity has, however, proved the mother of invention: Aberdeen has reaped the benefits of some innovative recruitment schemes. One of these allows council staff in non-teaching jobs to study to join the profession while continuing in their existing posts. Another, supported by the Scottish government, helps redundant oil and gas workers to retrain as science and maths teachers.

There have been recruitment drives in Ireland and Canada, yielding around 55 recruits from the Emerald Isle over three years - helped, says Gorman, by the General Teaching Council for Scotland agreeing to smooth stringent registration processes for overseas teachers.

Looking overseas

One Irish primary teacher, 25-year-old Tricia Geraghty from County Mayo, came to St Joseph’s primary after graduating from Edge Hill University in Lancashire last year.

She enjoys the flexibility of Curriculum for Excellence -“there’s more time to actually teach” - and says that she is trying to recruit to Aberdeen two of her teacher friends who are struggling with excessive paperwork in the English system.

Geraghty can see herself staying long-term, although she knows some Irish recruits have left after finding Aberdeen too expensive.

Two years ago, the “Northern Alliance” was formed to highlight recruitment difficulties in seven authorities, including Aberdeen. It started as a lobbying group but, at a time when the idea of regional cross-border working is topical, these councils are already working together on attainment and literacy projects.

Despite the innovation emerging from the recruitment crisis, the situation remains critical. Attainment has been improving in recent years, says Gorman, but with enough teachers for all subjects and all stages “that journey would be going even more quickly”.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters