Should we trust teachers’ choice of textbooks or defer to the DfE?

UK teachers use textbooks far less than their peers in countries that top education league tables, but appear to have a lot more say over which texts are chosen. However, in recent years the government has stepped up efforts to exert more influence in this area.

The Department for Education, for example, is providing match-funding for certain books as part of a £41 million programme to import East Asian maths-mastery methods and textbooks.

This has left teachers with a very restricted choice - so far, only one maths-mastery textbook has been granted DfE approval for match-funding.

But could an even more “top down” approach help to improve and standardise the quality of textbooks in UK schools, in line with those in the highest-performing nations?

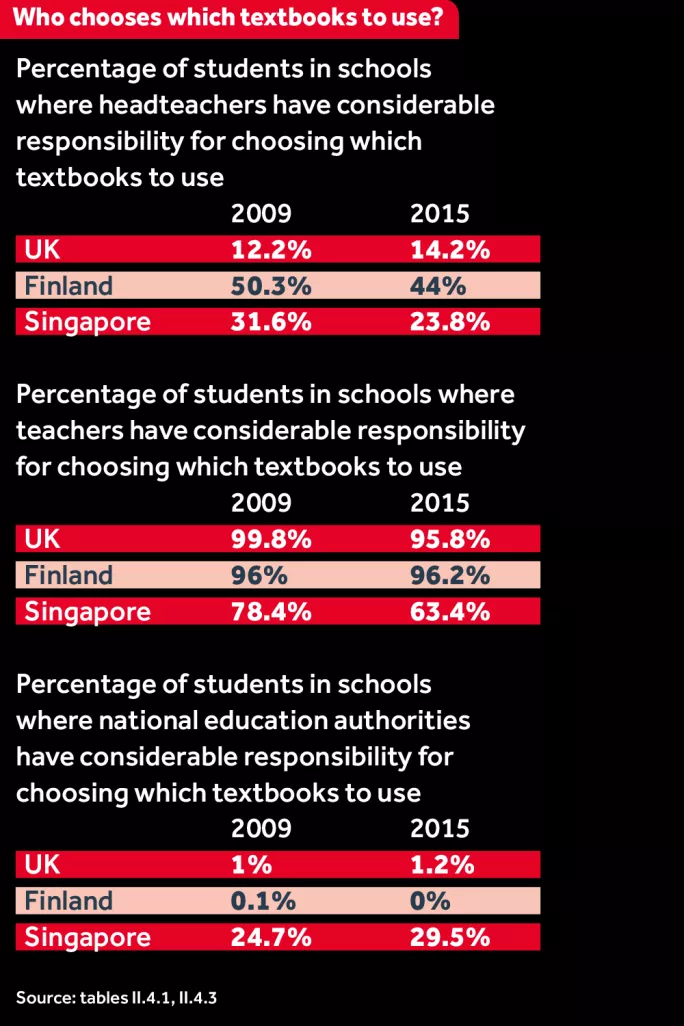

A Tes analysis of Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) figures shows that 95.8 per cent of 15-year-olds in the UK are taught in schools in which teachers have “considerable responsibility” for choosing which textbooks to use. In contrast, the figure is 46 per cent in Japan and 63.4 per cent in Singapore - which tops the Pisa league tables in maths, reading and science.

State approval

Textbooks in Singapore are developed and published by commercial publishers, but they undergo a review and authorisation process by the Ministry of Education before they are placed on the approved textbook list. Schools then select from this list.

In Singapore, it is the school governing board that largely chooses the textbooks (74.6 per cent of students are taught in these schools), with national educational authorities also playing a significant role (29.5 per cent).

However, “there is actually a lot of variation and context behind those numbers”, says Andreas Schleicher, head of education at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

He explains: “Countries like Japan and Singapore might appear top-down when it comes to textbooks, but they are actually doing a lot to involve teachers and educators in the design, development and evaluation of textbooks, and their alignment with the curriculum and instructional practice. So the single textbook that ends up in the classroom actually has quite a bit of [teacher] ownership.”

Tim Oates, group director of research and development at Cambridge Assessment, also highlights the systematic way in which other countries ensure teachers contribute to textbooks before they are distributed more widely.

“We can learn a great deal from international comparisons,” he says. “Not only about the form of the textbook, but how they are developed and approved.

“Both Finland and Singapore put a huge emphasis on having high-quality material developed for teachers. Here, we don’t have the same lead time or the processes that are established [elsewhere], such as lesson observation and research, to drive the textbooks.”

In Japan, it is not the central or regional authorities that are most likely to be cited as the choosers of textbooks, but headteachers. Just over three-quarters (75.5 per cent) of Japanese students are taught in schools in which it is the principal who has “considerable responsibility” for the textbooks used.

The corresponding figures for Finland and Singapore are 44 per cent and 23.8 per cent respectively, but in the UK, the number is as low as 14.2 per cent. In Finland, though, the trend is for decreased headteacher involvement: the proportion has dropped from 50.3 per cent in 2009, even though the figure for teacher involvement has remained high, at 96.2 per cent.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders and an author of English textbooks, thinks that heads in the UK are right to delegate the duty to their heads of department.

“I would be worried if headteachers were making these decisions,” he says. “No head is going to be as expert in, say, geography textbooks as their head of geography. It is about pushing the decision down to people who are best placed to make them.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters