Staff shore up learning amid wall collapse crisis

Flick through the press archives from after it emerged that 17 Edinburgh schools would be forced to close amid safety fears last April, and a picture of chaos starts to emerge.

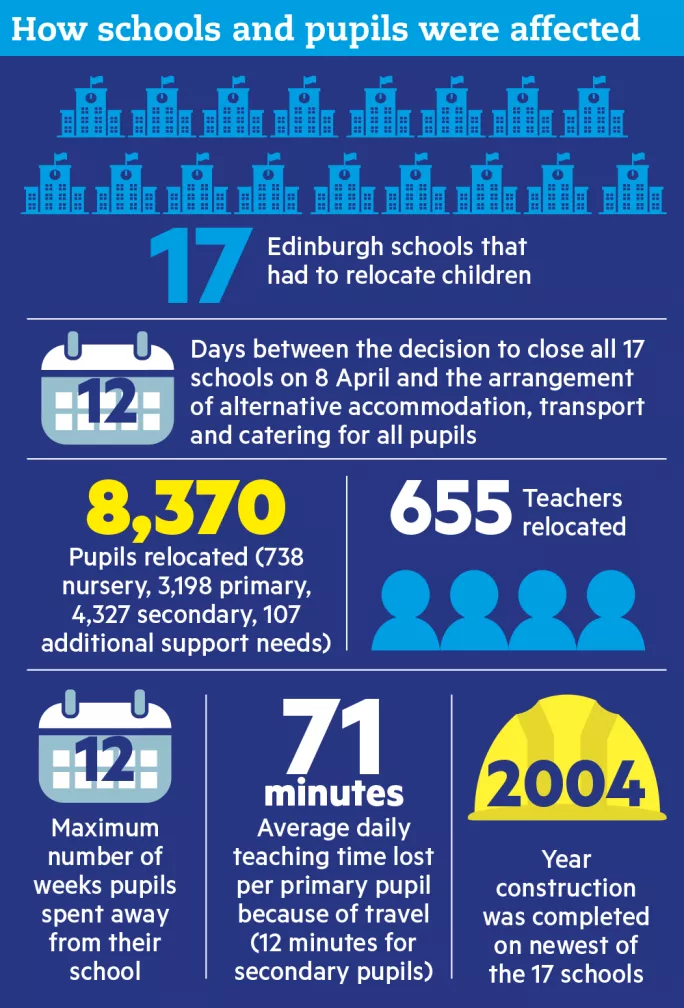

Storm Gertrude had ripped through Scotland in January 2016, tearing down a gable end wall at Oxgangs Primary on its way; last month, an inquiry found that only luck prevented anyone from dying. But that fortunate escape was just the precursor to upheaval that would involve almost 8,400 pupils and 650 teachers being moved from their schools after precautionary checks.

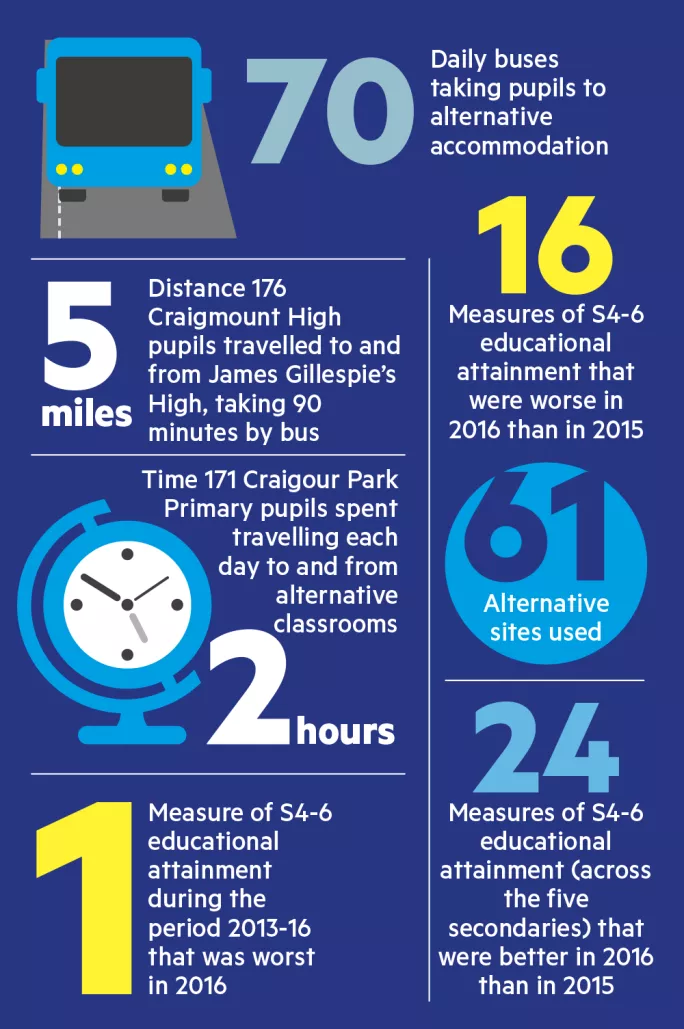

Professor John Cole’s inquiry revealed the scale of the crisis. The decision to close the 17 schools, including five secondaries gearing up for exams - for how long, nobody knew - was taken three days before pupils were due back from the Easter holidays. Some buildings did not reopen until after summer, pupils having spent 12 school weeks away. Dozens of buses criss-crossed the city at rush hour to 61 alternative premises, with return trips of up to two hours knocking an average of 71 minutes off primary pupils’ school day. Parents were understandably fretting on social media, leading to some lurid media reports: the ad-hoc classrooms were like “Saughton Prison”.

The blame for the defective school buildings has been widely discussed in the media since Cole published his findings, but the actual educational impact was largely ignored. Cole praises the “remarkable feat” of getting every affected pupil into alternative premises within “an extremely short time” - three days after the start of term for most, nine for others - and finds that any negatives are “likely to have been relatively limited”, or even “offset” by “unexpected positive impacts”.

Initial signs of this seeming triumph against the odds appeared in TESS shortly after the closures came into force (“‘We’re like a big family,’ say schools thrown together”, 29 April). Castlebrae Community High School’s roll tripled when it took in nearby Castleview Primary’s 240 pupils, who moved into a mothballed wing of the building after staff worked through a holiday weekend to clear years of accumulated junk.

The two schools found that working under the same roof brought mutual benefits, such as secondary pupils being able to help their younger schoolmates with reading, science, cookery and sport.

Speaking to TESS after the release of the report, Castlebrae head Norma Prentice said the schools were closer than ever and planning a joint staff trip to Loch Lomond. And seven previously disused classrooms were now being put to various uses by secondary students, including as a pupil-support base, games room and nurture base.

Liz Walshe, headteacher of Oxgangs Primary, told the inquiry that although pupils were ultimately “fed up” with being away from their school, there was “big excitement” initially and children returned with “lots of good ideas that they had seen elsewhere”.

“I expected to see a big dip in levels of attainment but in fact this never materialised,” she said. “In fact, in some cases I have seen something of an improvement. Overall, I would say that the experience for children has been at worst neutral.”

The most empirical evidence the report provides on the educational impact is S4-6 attainment statistics up to Advanced Higher - largely based, of course, on exams taken after pupils had been moved. TESS analysis shows that, of 40 measures (eight across each of the five secondary schools), 24 were better than in 2015 and 16 were worse. For the period 2013-16, only one of the 40 measures was at its worst level in 2016.

This was despite upheaval at schools such as 1,250-pupil Royal High. Here, pupils did not travel to other schools but most of the building was off limits, right up to the summer break, so 16 portable cabins were put up. Practical subjects were worst affected: home economics students had nowhere to cook, so were assessed on preliminary exams, coursework and photographs of dishes they had prepared; to be marked, cumbersome CDT project work - tables, mirrors, cabinets - had to be lifted out of off-limits areas by school staff wearing hard hats.

Pupils would find head Pauline Walker working at a desk in the corridor. Like a scene from a hospital drama, staff wheeled around trolleys with myriad computing and other paraphernalia. Pupils with autism were given time to familiarise themselves with their new surroundings before whole classes descended. Walkie-talkies coordinated everyone’s movements, and some teachers took learning outdoors - home economics pupils, for example, gained new skills in survival cookery.

“It was extremely stressful but the teachers really pulled it out of the bag,” Walker says.

‘Concentrated minds’

Teachers and school leaders tell TESS, however, that they cannot rule out some lingering problems. Andrew Jardine, Edinburgh secretary of the NASUWT Scotland teaching union, is head of English at Craigmount High, which suffered perhaps the greatest disruption, having to send pupils to three other schools and an old disused school. This “concentrated minds” and exams were not unduly affected, he says - with senior pupils largely away on study leave, there were worse times for the school to close.

The logistics led to some interesting experiments at Craigmount: for example, teachers tended to stay with the same class, like primary teachers. Overall, however, Jardine recalls last spring as “fairly traumatic and very unsettling”, and he has concerns that the disruption might have knock-on effects on pupils’ behaviour.

Similarly, Alex Ramage, an Edinburgh representative for the Scottish Parent Teacher Council, says that attainment at Craigmount improved thanks to teachers’ “superhuman” efforts. But he fears that current S4s in affected schools may struggle because most delayed starting the National 5 curriculum until after the summer.

It was extremely stressful, but the teachers really pulled it out of the bag

Pupils with additional support needs faced particular difficulties, the report finds, with children at Braidburn and Rowanfield special schools among those forced to move. One headteacher told the inquiry that it proved “impossible” to provide the usual access to specialist teachers and health professionals, with changes to daily routines most unsettling for autistic pupils - complex travel arrangements left some children with only three hours of education a day.

However, Braidburn acting head Euan Alexander reported to the inquiry that “it was not necessarily a bad experience in every sense”. Educational attainment targets were still met and children had the “very positive” experience of mixing with pupils from other schools - although not everyone got that opportunity - while staff bonded with each other and strengthened relationships with the professionals they encountered.

Overall, TESS found schools were surprised at how well they maintained business as usual. Walker had feared the novelty factor would lead to a “holiday camp” atmosphere that might damage learning even after pupils returned to their usual classrooms. However, looking back at last year’s upheaval now, she says: “It’s like it never happened.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters