Strong at school, held back by life

Are the dice of life still loaded against girls, whatever they do at school? From the final findings of Scotland’s outgoing poverty adviser, Naomi Eisenstadt, that is the “disturbing” impression that emerges.

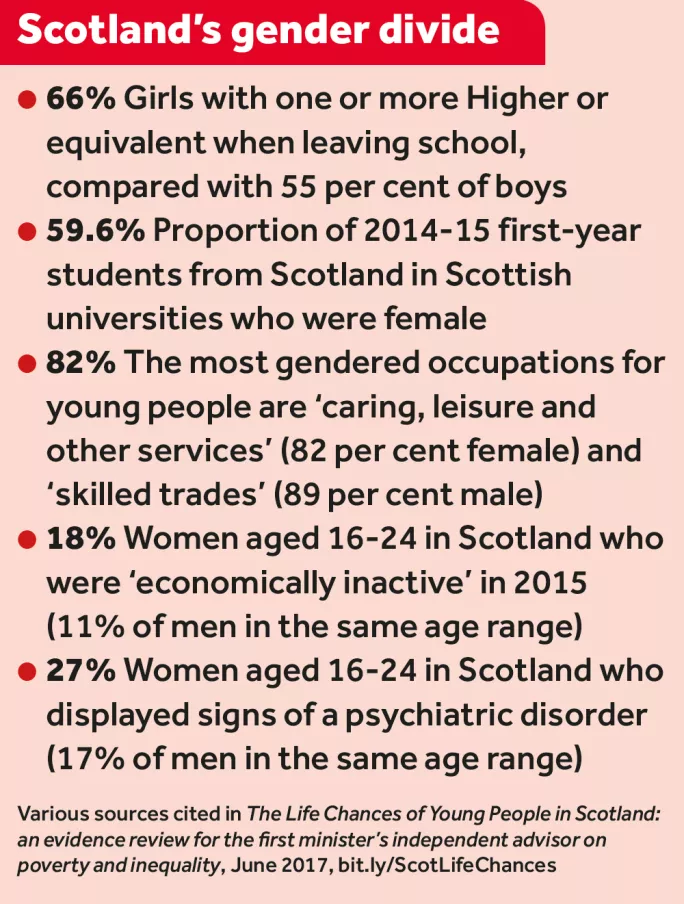

The academic reports that girls outperform boys at most stages of school. And even after leaving, young women are more likely to be taking part in education, particularly at university level.

But Eisenstadt also finds that “young women who leave school early with poor qualifications are likely to face worse labour-market outcomes than young men with similar characteristics”. Having some education is “less of a guarantee of quality employment than it once was”, she adds.

Research outlined in an evidence review shows that young women cite lower levels of life satisfaction and wellbeing than young men; are more likely to exhibit signs of psychiatric disorder; and report higher levels of self-harm. The roots are traceable to their school years, Eisenstadt concludes, and 15-year-old girls report particularly poor levels of mental health and wellbeing. “This is often not about medically diagnosed mental illnesses, necessarily,” she finds. “It’s more about how we tackle increasing levels of stress and anxiety.”

Some 80 per cent of 15-year-old girls in Scotland feel pressured by school work - compared with 60 per cent of boys - which is significantly higher than the European average. Eisenstadt also points the finger at the way boys and girls are encouraged to follow different paths at school.

“Continued gender segregation in subjects studied at school and beyond is associated with gender segregation in the labour market, with ‘feminised’ sectors tending to be low-paid,” states the evidence review.

To illustrate, she cites Scottish Funding Council figures showing that 93 per cent of further education students aged 16-24 pursuing a qualification in care - a particularly low-paid sector - are female, while the same percentage of engineering students are male.

‘End binary stereotypes’

Eisenstadt, who drew from a wide range of existing research and data, is calling for “a change in culture and public attitudes towards education and employment”. In her eyes, success on this front would be marked by more girls going into technology and more boys choosing a career in childcare.

Kara Brown, director of YWCA Scotland - The Young Women’s Movement, called the findings “disturbing” and said children learn “binary stereotypes” from an early stage that are “intrinsic in culture, education and family life”. Her organisation has heard from girls as young as 10 seeking opportunities to talk about mental health difficulties, or who felt boys were always leading group activities in class.

Helen Connor, a former EIS union president and a recently retired primary teacher, said: “There is still clearly work to be done at school level on self-esteem - girls often achieve more academically and, indeed, appear to enjoy school more than boys. However, in general, girls are less confident in their own ability and can also be less confident about expressing opinions than boys.”

She added that more could be done to challenge gender stereotyping in upper primary, perhaps by asking children to think about the divides in professions such as medicine, sport and politics.

Teenage pregnancy and young motherhood are widely seen as causes of social exclusion and are linked to poorer job prospects, Eisenstadt states. Taking on the bulk of caring responsibilities for children also limits women’s experience of work: a gender pay gap exists from early on in working life, with women more likely to be in low-paid sectors, such as care or hairdressing and beauty.

Erin McAuley, a 19-year-old student teacher and trade union activist who speaks on mental health issues, believes that while girls may appear on paper to do better educationally, this is often not reflected in how they act at school and university. “I think boys have more confidence - you’ll see more putting their hands up - whereas my [female] friends hold back,” she said.

Earlier this year, Tes Scotland reported University of Edinburgh research that suggested primary and secondary schools could do more to encourage girls to speak up about their views. A greater number of boys than girls felt that they had a say in every area of school life analysed, both in and out of the classroom, including rule-making, school uniform and the food offered in the dining hall.

Equalities secretary Angela Constance commented: “Closing the gender pay gap is one of our key priorities and we are already taking decisive action to address this, including taking steps to ensure women are better represented in senior and decision-making roles, and challenging pregnancy and maternity discrimination.”

The full-time gender pay gap in Scotland was 6.2 per cent last year, compared with a UK-wide gap of 9.4 per cent, added Constance.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters